INTRODUCTION

The United States health care system’s infrastructure regarding patients’ Electronic Protected Health Information records (ePHI) such as: Electronic Medical Records (EMR), digital imaging, revenue cycle and billing software (not limited to these) have evolved throughout the years, and 2021 marks the 25th year since the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) enactment [1]. The main focus of HIPAA law is: (1) The portability provision, (2) The tax provision and (3) The administrative simplification provision and it is the third provision that protects ePHI. This does not mean HIPAA has all the answers, but it does provide a greater level of security to patient information [2]. The Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) were signed into law in 1996. HIPAA was first created to improve the portability of health insurance for those people that were in between jobs; in other words, to ensure workers did not lose coverage when they were changing employment. In 1998, the legislation went further to improve the security standards to protect patient health information that was stored by health plans and in 1999; the Privacy Rule was proposed to restrict the disclosure of Protected Health Information.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule addresses how covered entities shall use and disclose protected health information (PHI). Covered entities can include health care providers, health plans, data clearinghouses, and business associates affiliated with health care organizations. Since One-Stop Care’s clinical team handles PHI daily, all staff must adhere to the standards set forth by HIPAA and prevent unlawful disclosure of highly confidential health information. The HIPAA Security Rule reinforces that all covered entities must ensure the protection and integrity of electronic PHI, safeguard against data security threats, and certify compliance by the applicable workforce [3]. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act went into effect in 2009. The law promotes the adoption of health information technology (HIT) and addresses privacy concerns with electronic health information storage and transmission. Violations of the act can result in a maximum penalty of $1.5 million. One-Stop Care will employ the use of electronic medical records (EMRs), and therefore will make the utmost effort to comply with the requirements of HITECH [3].

The review of HIPAA background and its counterparts such as, HITECH, ARRA, OCR, and DHHS, provided better understanding of HIPAA’s current underlying and growing issues. The lack of implementation of HIPAA law to its fullest extent has affected many organizations. HHS and OCR provide HIPAA violation cases with year, total violations fines, organization who is fined, date of fines, correction plan and OCR public settlement announcements. These violations can range from rights of access, data breach, HIPAA security rule violation, stolen encrypted technology, and other HIPAA violations. One can deduct that OCR is more heavily engaged in auditing health care organizations and assigning fines that easily reach several thousands of dollars. Prior to HIPAA, no generally accepted set of security standards or general requirements for protecting health information existed in the health care industry. At the same time, new technologies were evolving, and the health care industry began to move away from paper processes and rely more heavily on the use of electronic information systems to pay claims, answer eligibility questions, provide health information and conduct a host of other administrative and clinically based functions [4].

The Security Rule operationalizes the protections contained in the Privacy Rule by addressing the technical and non-technical safeguards that organizations call “covered entities” must be put in place to secure individuals’ “electronic protected health information” (e-PHI). Within HHS, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has responsibility for enforcing the Privacy and Security Rules with voluntary compliance activities and civil money penalties. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) required the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop regulations protecting the privacy and security of certain health information. The Privacy Rule, or Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, establishes national standards for the protection of certain health information. The Security Standards for the Protection of Electronic Protected Health Information (the Security Rule) established a national set of security standards for protecting certain health information that is held or transferred in electronic form. The Security Rule operationalizes the protections contained in the Privacy Rule by addressing the technical and non-technical safeguards that organizations called “covered entities” that must put in place to secure individuals’ “electronic protected health information” (e-PHI) [4].

Health plans are providing access to claims and care management, as well as member self-service applications. While this means that the medical workforce can be more mobile and efficient (i.e., physicians can check patient records and test results from wherever they are), the rise in the adoption rate of these technologies increases the potential security risks. A major goal of the Security Rule is to protect the privacy of individuals’ health information, while allowing covered entities to adopt new technologies to improve the quality and efficiency of patient care. Given that the health care marketplace is diverse, the Security Rule is designed to be flexible and scalable so a covered entity can implement policies, procedures, and technologies that are appropriate for the entity’s particular size, organizational structure, and risks to consumers’ e- PHI [4]. Since April 2003, OCR has investigated over 298,834 HIPAA complaints, while over 1,133 compliance reviews were initiated and about 290,026 (97%) of these cases were successfully resolved as of May 31, 2022.

Allen [1], describes HIPAA as “a framework of evolving regulations that’s revised periodically in response to demands of biomechanical innovation and public health in the digital age” (p.1). It was known as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 which was a step towards greater health information privacy. Due to the growth of patient medical records, HITECH has faced many obstacles in protecting/policing the collection of ePHI, storage of ePHI, transfer of ePHI and the sharing of ePHI. Again, the large number of complaints against the lack of protection of ePHI, even after the HIPAA Act and the HITECH Act, has forced the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights (OCR) to finalize the omnibus rules on January 25, 2013. This meant that all health care and non-health care organizations would be held responsible for the breach of ePHI as a violation. “The omnibus rules, however, expanded the reach of HIPAA to include all business associates that create, receive, maintain, or transmit protected health information” [5].

Before HIPAA existed, patients’ medical information was not protected. Medical doctors, nurses and other medical staff could easily log into any computer and look up patient information. If they needed to share patient information, they could do so without a second thought or any restrictions. The implementation of HIPAA laws has brought about much change, but it has not been easy or quick. HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and the first change proposed was the Security and Electronic Signature Standard Rule (SESR) in August 12, 1998 and the Privacy Rule was proposed in November 3, 1999. The Privacy Rule did not go into effect until March 16, 2006. Once this rule went into effect, it allowed for OCR to conduct investigations into HIPAA violations. This led to legal proceedings of HIPAA violations as well. It took over seven years to establish a new rule in order to provide a framework for policing and holding health care organizations accountable for a lack of protecting ePHI. It took 13 years for full implementation of HIPAA laws from HIPAA enactment in 1996 to the first violations fine in 2009.

Due to the lack of enforcement, the nation is faced with the lack of HIPAA law regulations through the OCR. It has been suggested that out of more than 33,000 complaints up until 2008, only 8,000 were investigated and no financial penalties were issued, leading to the HITECH Act Signing. This Act pushed the use of electronic record use in health care organizations. HITECH is introduced as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA). There were many incentives for health care organizations to switch to electronic record keeping. The HITECH and ARRA Acts allowed for the centralization of ePHI. With these changes, 2009 proved to be the first year in which OCR cracked down on organizations that still did not comply with HIPAA laws. According to HHS, CVS Pharmacy was the first to receive a financial penalty and CVS Pharmacy Inc. was ordered to pay $2.25 million for improperly dumping patient health records. Two thousand and twelve marks the Final Omnibus Rule and the OCR pilot audit ends with the final issued omnibus rule in 2013. From 2015 up until today, there have been HIPAA audit delays and faced with the restrictions of COVID-19, there are many more delays. HIPPA and all its counterparts must continue to evolve with the world of ever-changing rules and systems.

With the aforementioned changes, we have a better definition of the 4-tiers of HIPAA violations. In order to better understand violations, we must look at the 4-tiers used to fine those who violate HIPAA law. HHS indicated that the first-tier affects entities that did not know and could not reasonably have known of the breach. An example of the first-tier violations can be outlined as follows: A Hospital system has a breach in which a hacker walked into the hospital and put a bug into the system in order to hack it. The assailant is not employed by the organization. The organization has no idea the hack is taking place and therefore the hospital has no idea they are the victim of a crime that they will have to pay for dearly. Even though the hospital did not know nor could they have reasonably known, they will still be held liable for not implementing the adequate safeguard in order to prevent such threats to breach of patient information. This first-tier was reported to be punishable with fines from $100-$50,000 per incident up to $1.5 million. The second-tier affects are to covered entities who knew or by exercising reasonable diligence would have known of the violation, though they did not act with willful neglect. An example of this tier is: A hospital hires an IT consultant to establish a firewall in order to protect their patient’s information.

The IT consultant tells the hospital executive team they will only have one year in which the firewall will hold up and they will need to update and add more layers of protection. The hospital says they agree and do not contract with this IT consultant for a follow up update of their system. They decide they will do it once the contract is complete at the end of the year. The executive team is busy at the end of the year and they forget to call the IT consultant to renew their firewall. Six months later, the hospital has a breach of patient information. The executive team could have prevented this breach of data if they would have diligently kept to their executive fiduciary responsibilities. Due to their negligence, the hospital could be or will be fined. Second-tier violations range from “$1,000-$50,000 per incident up to $1.5 million.” The third-tier violation affects those covered entities who willfully neglect and correct the problem within a 30-day time period. An example of this tier is a patient who believes their ePHI has been compromised and files a complaint with HHS to further investigate the doctor’s attended clinic.

The private practice receives a visit from OCR and if it is deemed to have violated a HIPAA law, OCR allows this clinic to write a 30-day correction plan and to fix the current issues at hand. The clinic writes a plan of correction and effectively corrects the issue, hence securing the patient EHR. The fine for this tier is $10,000-$50,000 per incident up to $1.5 million. The fourth-tier was reported to consists of the covered entity that acted with willful neglect and that failed to make a timely correction. An example of the fourth-tiers is: A hospital knowingly decided to not train staff to follow HIPAA guidelines. A patient noticed that a nurse is sharing their HIV positive status with another nurse in the hallway (this hallway is full of other patients and hospital visitors) and the patient sees his friend pass by as the nurse mentioned the patient’s name and positive HIV statues. This patient reports the hospital to HHS and there is an audit conducted. The hospital does not care to create a 30-day correction plan and continues to train staff without any guidelines of HIPAA laws. This hospital is in violation of HIPPA’s fourth-tier of which they can be fined “$50,000 per incident up to $1.5 million.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

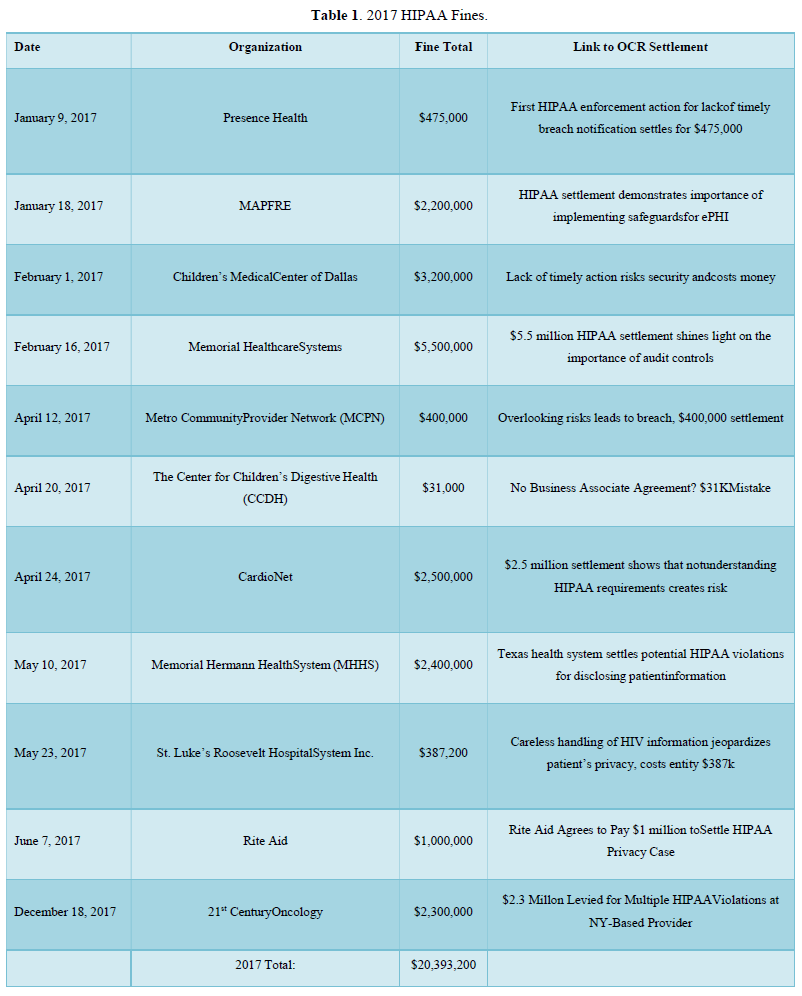

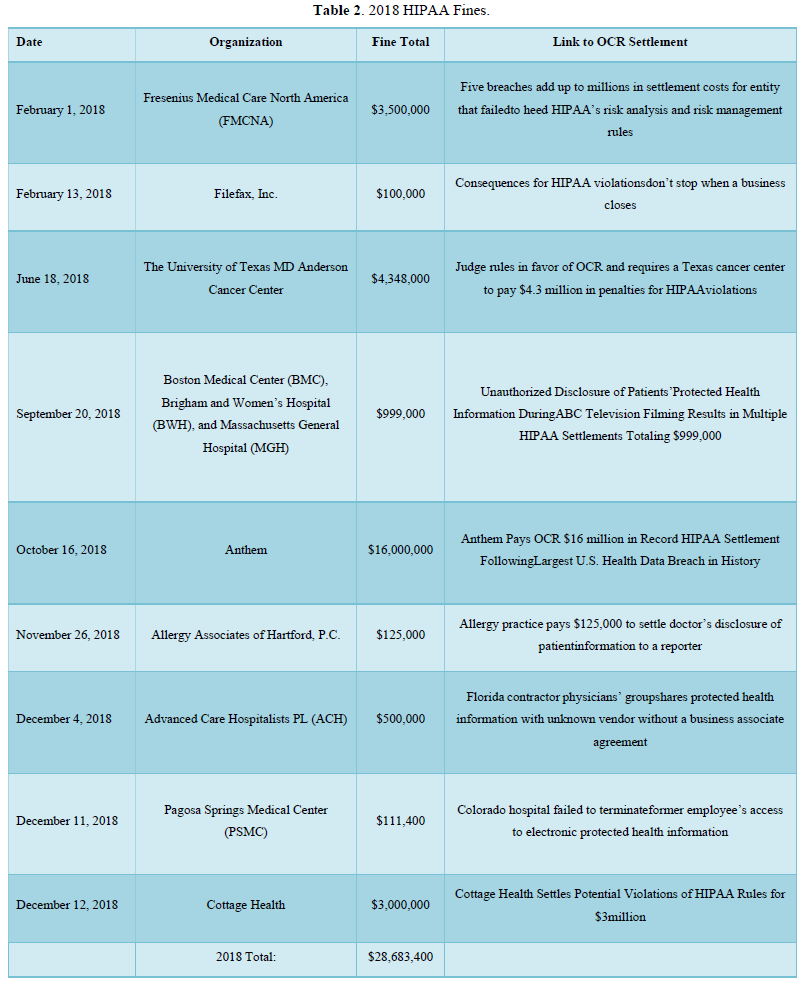

One of the major issues regarding the subject of (HIPAA) violations is encryption. The largest fines for health care organizations are derived from the lack of encryption of (ePHI) and (EMR’s). In the (OCR) settlement announcements, one can have a better understanding of total fines per year. Starting with 2017, HIPAA fines totaled $20,393,200.00. These fines included, but were not limited to: lack of timely breach notification, lack of safeguards for ePHI, disclosing patient information. In 2018, the total HIPAA violation fines were $28,683,400.00. This year included the largest U.S. health data breach in history. Anthem paid OCR $16 million for the data breach. In 2019 and 2020, the fines totaled $28,824,900.00. These fines outline some of the major obstacles that need to be addressed.

Other ramifications for a lack of encryption of ePHI lead to violations which in return hurt the health care organization economically, it diverts time and resources away from more pressing matters. It is counterintuitive to not want to spend the time initially on structure, education, and HIPAA updates to the health care organization. When reviewing secondary data sources regarding HIPAA violations, the information found is overwhelmingly screaming for change towards a more positive direction. Year after year, there are violations that cost many thousands and even millions of dollars. These costs are one of the reasons behind inflation cost in health care organizations. In order to balance out the financials in the organizations affected, executive teams strategize and raise costs to regain lost profits due to HIPAA violations.

There is also the theory that HIPPA violations are merely a means to an end. With such high-cost violations, it begs the question, why do HIPAA violations worth millions of dollars still occur on a yearly basis? According to Gaia [6], there are also monetary incentives used to persuade nurses, doctors, insurance agents, and relatives to violate HIPAA regulations and privacy regulations. The current issue is that 45.9% (240/523) of nurses in these scenarios said there is a price they are willing to except in order to breach ePHI. This price ranged from $1,000 to $10 million [6].

The percentage for doctors was 35.4% (185/523) with the same price incentive as nurses.

Insurance agent’s scenario outlines a 45.1% (236/523) of the participants who would take a monetary incentive between $1,000 and up to $10 million. The most alarming and impressive numbers come from family relationships. One of the scenarios was outlined as follows: the mother of the person committing the HIPAA violations did not have insurance coverage and therefore a HIPAA violation would have to occur. This group totaled 78.4% (410/523) of participants who would violate HIPAA violations and regulations for an incentive of $100,000 from a media outlet, including politician’s medical records. The scenario-based questionnaire study also created a scenario where a person is incentivized by obtaining a famous reality stars medical records in exchange for $50,000 that would be used to help transport a friend in an emergency setting. These scenarios outline the fact that people of all types and positions are willing to violate laws and regulations for a price, whether it is for economic gains or tied to emotional needs. Although the scenario-based questionnaire study concluded that there is a price for violations, one of the key findings was that people who perceived they would be caught would be less likely to release private information [6].

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

This study is intended to give the reader a better understanding of the current U.S. standing on HIPAA regulations, violations and what can be done to prevent such events and the associated costs. Title II of HIPPA directly addresses and protects the security and privacy of patient health information [7]. Employees need to comply with all aspects of HIPAA, as it continues to provide patients with direct and obligatory rights to privacy [8]. Therefore, the main purpose of the study is to access the current U.S. standing with HIPAA regulations, violations and what can be done to prevent such events and associated costs. Due to the lack of action to enforce provisions, guidelines and bylaws, there is a culture of change that needs to be awakened within health care organizations; this study also outlines the negative effects and costs related to neglecting HIPAA guidelines to protect (ePHI).

Looking into HIPAA fines from 2017 to 2020, the total cost of HIPAA violations was $77,901,500.00 [9]. One can deduct from this data that there is much room for improvement when it comes to enforcing and policing health care organizations in regards to HIPAA guidelines. When comparing different violations, the major violations at over 1 million dollars are those with a weak infrastructure for encryption and redundancies attached to ePHI. This study mainly focuses on what can be done to educate staff regarding the importance of HIPAA, update policies to reflect processes and procedures (with room for new HIPAA guidelines), and a proper road map to navigate the world of encryption.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

The job of encryption requires that the organization purchase software and physical equipment in order to protect ePHI. Not only should there be software and hardware, but there should be a set of policies and procedures in order to better understand who can access data, store, transfer and share. The most damaging and high-cost HIPAA breach violations, according to OCR reporting’s, are those that hack the internal system of a health care system or hospital in order to access ePHI. This issue arose from the implementation of HIPAA’s HITECH provision to transitioning all paper medical records to ePHI. These changes brought about electronic record systems to input data, track data, store data, and share data between health care providers and practicing covered health care entities. These entities have implemented or updated their record tracing data systems and encrypted them for security measures.

Also, who can store, who can access it, and who the health care providers can legally share it with. There is also a need for decryption, as well as encryption “in backing up, and transmitting electronic patient information” [10].

Therefore, there is a need for storage of this data and safe point verifications systems or destruction of data if it is no longer needed. There should be a firewall specific to the practice and or individual departments where data is collected, shared and managed. The implantation of these system for many years have been feared due to the upfront high cost of implementation.

This would include the cost of and time usage in not only purchasing software and hardware, writing new policies and procedures, training staff to abide by current and updated HIPAA guidelines, but also training staff to use new software system.

RESEARCH METHOD

The research design relied on secondary data sources that included publicly available data on Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) violations. Documentary data includes the articulating and the interpretation, then the reflecting (also reflective) of the interpretation of the empirical material, and finally, the generating of theory as a multidimensional typology [11]. The findings in this research rely on a reexamination of published research within the last five years, especially during this COVID-19 period. Given the extensive literature review and analysis on HIPAA violations, a deductive approach was pursued in the analysis of the findings [12,13].

This research also utilized a non-systematic meta-analysis research found in the major databases under the terms HIPAA, OCR, ePHI, HITECH, EMR and ARRA since the year 2015, and was conducted in order to report the major primary findings. The review for this research included peer-reviewed publications that studied and investigated new approaches to planning and development that is included in the references listed for this study. Articles from non-peer-reviewed publications were also included and partially listed on this review, based on relevancies. The remaining articles were retrieved for further screening and were included in the review, as they evaluated urban health. Other bibliographies included in this research were hand-searched and therefore, no limitations were placed on study scope. Most of the results generated for this study were extracted from OCR and HHS monitoring reports to date, as a result of comparative analysis. Other findings from peer review research were also compared with the findings from major organizations, such as HIPAA, HSS, OCR, HITECH, ARRA, TJC, and CMS in order to report accurate results for this research.

Several research questions were derived from the Scenario-Based Questionnaire Study, such as who pays for it, and is there a higher incentive to allow a breach of data in order to gain higher future ROI by providers, payers and or government officials? These questions were generated to determine the difficulty with policing and enforcing at a large scale, the costs associated (encryption, trainings, adding new and continues HIPAA policies and procedures, the cost and time consumption of implementing a new effective EMR system) and potential incentives to breach HIPAA data and physicians not trained and violating HIPAA; with the pretense that the major issues with HIPAA violations and regulations prove that there are still too many violations. There is a lack of oversight in policing violations [6].

FINDINGS

The findings were derived from peer reviewed journals, hard data, government reporting agencies and secondary sourced data. This qualitative study focused on articulation, interpretation, and reflective work on empirical material. The data analysis and interpretation presented the following conclusive information. HIPAA was not well designed early on to police/enforce its laws. HHS and OCR were designated to audit, assign fines and report findings. These organizations have been working on better regulation of the violations of HIPAA in covered entities, but are not efficiently succeeding in their intended overall purpose.

Health care organizations are mandated by CMS to be accredited by TJC and/or other organizations, such as URAC. They are mandated to be accredited in order to receive payment from CMS for services rendered to patients. Accrediting organizations certify covered entities, yet they still receive fines from HIPAA violations, such as breach of ePHI. Part of the accrediting process involves having an encryption with secure software and hardware in order to protect ePHI. It is concluded that health care administrations lack in establishing policies and procedures to be in-line with the HIPAA Act. Health care administrators also do not take the time nor invest in new health care record systems, due to high cost and lack of ROI. There are also health care workers including doctors, nurses, insurance companies, and others who are willing to sell ePHI for personal economical and personal/emotional circumstantial gains.

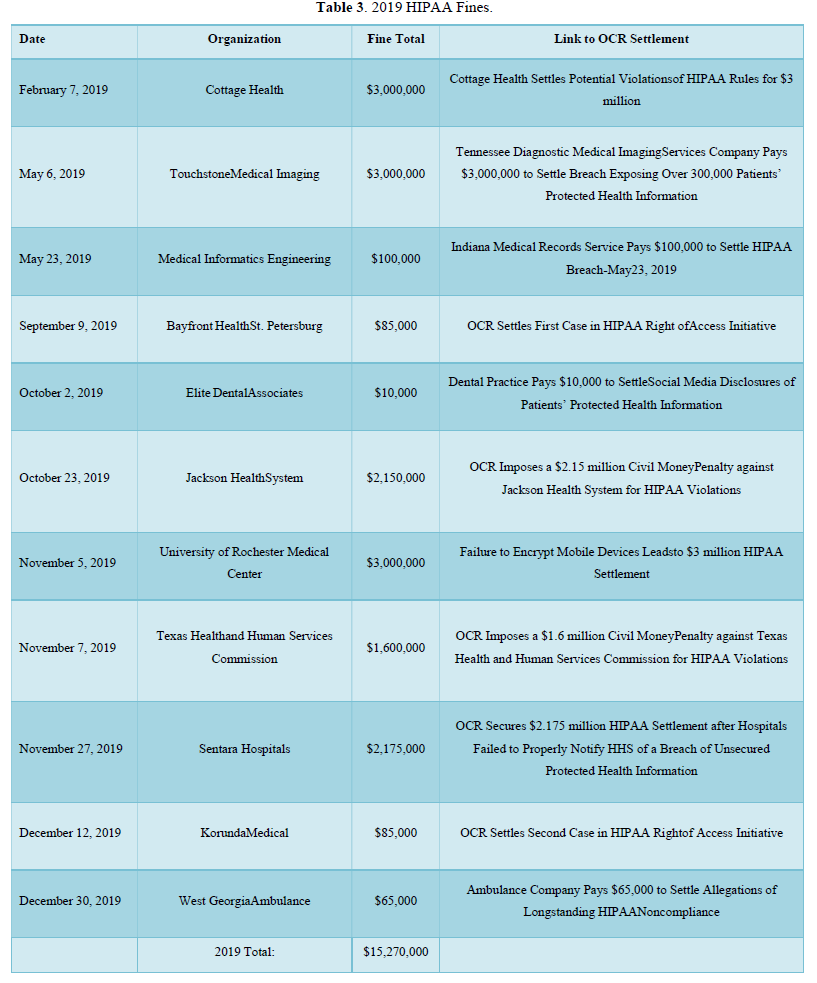

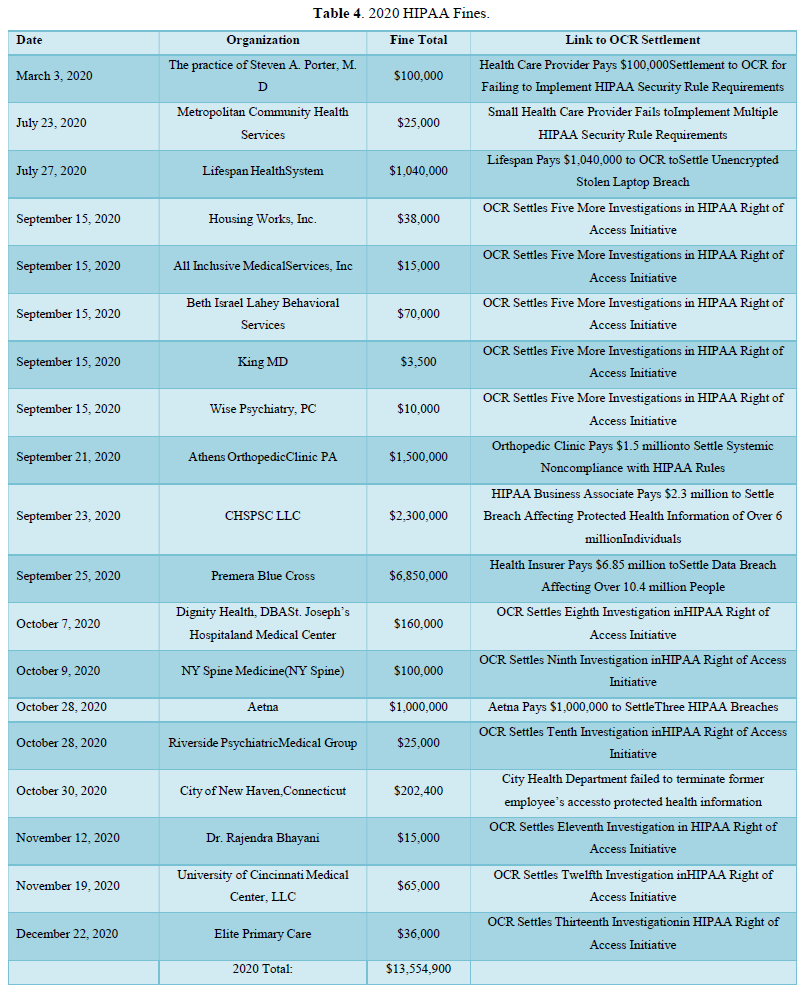

One of the major concerns regarding HIPAA violations is the lack of encryption for covered entities. HHS and OCR announced HIPAA fines for 2017 that totaled $20,392,200.00. These fines include, but are not limited to lack of timely breach notification, lack of safeguards for ePHI, and disclosing patient information. In 2018, the total HIPAA violation fines were $28,683,400.00. In 2021, the largest U.S. health data breach in history occurred, for which Anthem paid OCR $16 million for that data breach. In 2019 and 2020, HIPAA fines totaled $28,824,900.00. These fines highlight some of the major obstacles that prevent the healthcare providers from following HIPAA guidelines in safeguarding patients’ privacy. These obstacles can include training staff, updating software and hardware systems for encryption in the hospital(s), and updating policies and procedures to reflect new HIPAA polices and guidelines.

The “data breach of ePHI” is the highest HIPAA violation in cost across several years and for several organizations. If data breach of ePHI is one of the highest costs for HIPAA violations, one can deduct that this would be one of the major issues with covered entities. Therefore, covered entities should be looking at how to protect against a breach to ePHI. Another set of data presented is the overall cost of violations. In 2020, 19 organizations were audited and fined. There were 5 organizations that were fined more than $1 million, but 14 others were charged violation fees in the thousands. In 2019, only 10 organizations were fined of which 5 were charged more than $1 million. In 2018, only 9 organizations were fined out of which 4 were charged more than $1 million. Two thousand and seventeen brought about 11 organization violations, out of which 7 were charged more than $1 million for violations.

The United States health care system’s infrastructure regarding patients’ Electronic Protected Health Information records (ePHI) such as: Electronic Medical Records (EMR), digital imaging, revenue cycle and billing software (not limited to these) have evolved throughout the years, and 2021 marks the 25th year since the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) enactment [1]. The main focus of HIPAA law is: (1) The portability provision, (2) The tax provision and (3) The administrative simplification provision and it is the third provision that protects ePHI.

By understanding the history of HIPAA and its counterparts, The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH), The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), and The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), one can have a better understanding of HIPAA’s current underlying and growing issues. HHS and OCR provide HIPAA violation cases to the public with year, total violations fines, organizations fined, date of fines, correction plans and OCR public settlement announcements. These violations can range from rights of access, data breach, HIPAA security rule violation, stolen encrypted technology, and other HIPAA violations. One can deduce that OCR is more heavily engaged in auditing health care organizations and assigning fines that easily reach thousands of dollars. This research focuses on the cost of violations between 2017-2020 (excluding 2021, due to COVID-19 restrictions) [1].

The primary finding for HIPAA violations as reported by HHS and OCR for the years 2017-2020 are as follows [9]:

Table 1 below describes the organizations that have violated HIPAA law from January 1, 2017-December 31, 2017. This table outlines the organizations who have been found violating HIPAA law and audited by OCR. The table displays date of organizations violation, name of organization, fine total in U.S. dollars, and the reference to the breach and correction plan.

Table 2 below is a compendium of HIPAA violations from February 1, 2018-December 12, 2018. This table is a compendium of violation fines, name of organizations and OCR settlements.

Table 3 below is a compilation of data from February 7, 2019-December 30, 2019. This table presents HIPAA violations per organization, fine total and Specific HIPAA violations charges. This year accounts for the largest HIPAA fine up to date at a total of $16 million dollars for a data breach. In 2019, the data shows a drop in charges and raises the question, why.

Table 4 below presents HIPAA violation data collected by OCR which represents March 3, 2020-December 12, 2020. This data includes HIPAA fine totals, organization names and OCR settlement. Table 4 has the greatest number of organizations who have been fined for the year 2020. There are 19 organizations who have been fined which marks the highest year for the most amount of organizations fined by OCR for violation of HIPAA law.

When considering incentives or bribes in order to breach HIPAA laws, data was compiled through a design of 5 questions regarding HIPAA violations. These questions are asked in the perspective of a working nurse scenario, doctor, insurance company, and personal context. The data presented outlines the fact that people are willing to breach HIPAA law if they can have a monetary gain and not be caught. The level of percentage varied with the different groups tested but, ultimately there was a price in which people of all categories were willing to breach HIPAA law by releasing ePHI for one reason or another. It is alarming to know that “79% of the participants would accept money to save their mother and 65% would accept money to save their best friend” [6]. When comparing nurses, doctors, insurance companies, and a personal context, it is inevitable that the personal context will have heavier weight when balancing the life of a loved one compared to the potential negative outcomes or cost. Although, nurses ranked at 47% for admitting they would accept a certain amount of money to provide patient data. Thirty five percent of doctors were willing to sell patient data and 45% of insurance companies would also sell patients data. Over all, all different types of categories for participants proved that people could be swayed by monetary compensation [6].

SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The HIPAA ACT has a lot of room for improvement, but it is well on its way. Since HIPAA’s enactment, there has been a wind of progression in a positive way towards better rules, such as the Omnibus Rule and the policing of HIPAA violations by OCR and reporting by HHS. HHS and OCR’s data concludes that there is still a problem with the breach of ePHI. Covered entities continue to violate HIPAA laws and fines are only increasing year after year. Although, some health care organizations are doing their best in preventing HIPAA violations, there is still much room for improvement. There is a lack of policy and procedural implementation for training, educating and reviewing progress with employees regarding HIPAA information. The executive team is doing what is required by law to a degree in order to maintain a functioning covered entity and also, in

order to receive reimbursement for services rendered. The executive team is still working with old outdated software and hardware which leaves the organizations vulnerable to data breaches. Health care organizations (covered entities) lack a structure of ethical and moral platforms in order to better train their employees. Different types of employees are willing to sell patient data for a monetary benefit and a greater number of employees are willing to breach HIPPA law and sell patient data in a personal context [6].

Patients are under-protected and the most vulnerable population to have their ePHI breached, due to the lack of executive oversight of health care covered entities. HIPAA is a great start in protecting patient’s health information from being manipulated and sold to other benefiting covered entities. OCR is a great addition to police and fine those who have violated HIPPA laws. HHS does a great job of reporting fines, organizations who have violated HIPAA, and their correction plan in order to be in good standing with HIPPA law. The matter of fact is that there are still violations and they are only increasing. There has been a void in the past to police HIPAA violators and now, the data looks like there is much to be done. OCR might be overwhelmed and underrepresented in comparison to the covered entities.

The year 2017 had a violations total cost of $20,393,200.00. This year included organizations such as: Memorial Hermann Health System (MHHS), Rite Aid, 21st Century Oncology, Memorial Healthcare Systems and others. The year 2018 had a violations total cost of $28,683,400.00. This included organizations such as Anthem, Cottage Health, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) and others. The year 2019 presented a total violation cost of $15,270,000.00. This year targeted organizations such as: Sentara Hospital, Texas Health and Human Services Commission, University of Rochester Medical Center, Jackson Health System, Touchstone Medical Imaging and others. Thus far, we have had fewer health care organizations who are charged more than $1 million in violations. In 2020, the total violations cost was $13,554,900.00.

According to Yaraghi and Gopal [5], the Office for Civil Rights compiled, deducted and provided the following data for a 3-month period from January 25, 2013-September 23, 2013. There are many active professional physicians in the United States and according to the number of violations reported, one can account for “an average of 2.17 privacy breach incidents” that “take place per 1,000 professional active physicians in the United States (p.1). These numbers derived from further analyzing the number of individual breach incident by covered entities and the types of breaches of privacy. Included in this study, we analyze hacking/IT incidents, theft, loss, unauthorized access, other, and improper disposal. These incidents are calculated on average to affect -87,760 individuals, while a breach incident among business associates affects 98,803 individuals. So far, these breaches combined have undermined the privacy of 175,047,905 patients in the United States. These numbers account for health care cover entities and do not account for those who are not cover entities, nor do we have a real number for those who are violating HIPAA law and are not reported or audited by OCR [5].

When considering incentives or bribes in order to breach HIPAA laws, the following data was compiled through a design of five questions regarding HIPAA violations. These questions are asked in the perspective of a healthcare employee scenario, doctor, insurance company, and personal context. The data presented outlines the fact that people are willing to breach HIPAA law if they can have a monetary gain and will not be caught. The percentage varied with the different groups tested but, ultimately there was a price in which people of all categories were willing to breach HIPAA law by releasing ePHI for one reason or another. It is alarming to know that 79% of the participants would accept money to save their mother and 65% would accept money to save their best friend. When comparing nurses, doctors, insurance companies, and a personal context, it is inevitable that the personal context will have heavier weight when balancing the life of a loved one compared to the potential negative outcomes or cost as outlined in the study. Nurses ranked at 47% for admitting they would except a certain amount of money to provide patient data. Thirty five percent of doctors were willing to sell patient data and 45% of insurance companies would also sell patient’s data. Overall, all different types of categories for participants proved that people could be swayed by monetary compensation to violate HIPAA law [6] aspect of HIPAA is accreditation. Accreditation from different organizations is encouraged and at times demanded by other governing bodies in order to receive payment for services rendered. An intended outcome from accreditation services is the result of better outcomes. A recent study conducted consisted of 4,400 hospitals out of which 3,337 were accredited (2847 by The Joint Commission) and 1063 underwent state-based review. There were “4 242 684 patients aged 65 years and older admitted for 15 common medical and six common surgical conditions and survey respondents of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems (HCAHPS). The results proved that there was no significant statistical variance from those organizations accredited by The Joint commission (TJC) or those accredited by independent organizations. There was no conclusive data that proved that The Joint Commission provided better outcomes when compared to organizations accredited by independent organizations [14].