274

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Any obstacles or barriers in being able to efficiently carry out these professional duties can be a source of occupational stress. However, it can be said that the most threatening of them all, is losing a therapy patient, to suicide. Loss of a patient to suicide, is a climacteric event with implications on the therapist’s personal life, professional functioning, mental health and wellbeing. Chemtob [1] compared the severity of distress in 49% of therapists, post a completed suicide of a patient to those who needed treatment after a parental loss. Due to its wide-ranging consequences, patient suicide can be considered an occupational hazard for psychologists and psychiatrists [2]. Menninger [3] found that patient suicide was the most reported cause of a therapist’s anxiety. The predominant feelings experienced by the therapist were shock, guilt, grief, anger, doubt on professional adequacy and discouraging her from taking up further suicidal cases. Hendin [4] explored emotional reactions of therapists who were survivors of patient suicide. Authors reported that patient suicide is a critical event for a therapist, triggering overwhelming emotional reactions which had implications for their wellbeing. These even impacted the therapist's decision to further accept patients with suicidal ideations into their practice. Grad [5] reported major feelings of guilt, in the survivors. Therapists who have experienced loss of a patient to suicide reported major feelings of guilt, depression, guilt, and loss, along with increased caution in conferring with colleagues. for the treatment of patients among the psychiatrists and therapists who had experienced loss of a patient to suicide. Wurst [6] suggested that 39.1% of all therapists suffered severe distress. Treating psychologists who lose a patient to suicide, incorporate the catastrophic event into their personal and professional lives [7].

The grave concerns associated with losing a patient to suicide are not very much talked about and therefore, planning any efficient and accessible management for these issues has also not received much attention. This negligence itself is an indication of the “elephant in the room” situation, where one of the most profound concerns related to the mental health of a mental health professional is not being given the required clinical attention. It could be hypothesized that such ignorance arises from one’s inability to talk openly about these experiences without doubting oneself and feeling ashamed as well as inferior. Though the loss of a patient to suicide, occurs in a professional space, yet it is an extremely personal experience for the therapist. This loss is difficult to understand for non-professionals and sadly, lacks the desirable support in the professional community due to the lack of professional conversations about the occupational hazards of a therapist’s life that deals with trauma, sadness, disappointment, isolation and awkward moments.

The lack or sheer absence of a comforting environment to process the trauma, makes one experiencing such a situation, feel isolated and leaves one, silently mourning. More often than not, this can prolong emotional injuries, posing various mental health concerns for the therapist. Kolodny [8], while emphasizing the value of crisis preparedness, for professional trainees, has highlighted the importance of facilitating effective support and supervision for processing grief. Brown [9] observed the extensive impact of isolation on the mental health of individuals and proposed that secrecy, silence and judgment put together, create the most conducive environment for shame, to grow exponentially.

Neff [10] popularized the concept of self-compassion, a psychological construct that serves as a buffer against difficult and traumatic life circumstances. Cousineau [11], acknowledging the far-reaching benefits of self-compassion, termed it as- “The Kindness Cure”. Self- compassion is a cognitive-emotional asset that addresses the issues at different levels. Neff [10] identified the multilayered nature of self-compassion. She proposed three dimensions for it- Self criticality v/s self-kindness, isolation v/s common humanity, and lastly overidentified v/s mindfulness. She suggested that humans tend to harshly criticize themselves for making a mistake. She also noted that we are capable of offering kindness to others, if they committed the same mistake as us but we seem to take an unforgiving stance for ourselves. Self-kindness involves being able to offer the same compassion to oneself that one would extend to a loved one, faced with disappointments. The other aspect of self-compassion involves the tendency to see oneself, “as the only one”: the unfortunate one, the worthless one, the most helpless or hopeless one. Humans, when faced with crises or failures, often jump to the conclusion that the world, universe and God, are all against them or that everyone else is doing better or even that no one faces as many troubles as them. This doesn’t only add to the misery by fueling the agony but also shifts the focus from the problem at hand and generalizes its perceived negative impact on one’s overall life. The self-compassionate counterpart of isolation is the ability to see the ups and downs of life as a part of human experience and being able to appreciate that everyone goes through something. This isn't to draw a comparison of any kind but rather to develop a more realistic world view and re-calibrate one’s expectations from life. The ability to be grounded in the principle of common humanity acts against the distraction and added suffering brought along by isolation and helps one focus on solving the prevailing concerns. At the last level, self-compassion acts against over identification with problems. It helps one navigate through the emotional overwhelm caused by the problem by engaging in mindfulness. Mindfulness helps one manage the overpowering emotional turmoil, bring back the psychological homeostasis and approach the circumstances from a balanced perspective. Owing to its extensive clinical implications for psychological well- being, self-compassion can be termed, a simple yet extremely powerful tool.

Often, when an individual feels psychologically uncomfortable but cannot access professional help from a therapist, a simple yet effective self-help intervention that can assist in recovery, is desirable. Held [12] suggested that self-compassion can assist in trauma related guilt repair and in the absence of a therapist, this self-help intervention can enhance the self-efficacy of individuals by making them feel comfortable in their own skin and enhance their wellbeing.

The aim of the present paper is to highlight the conflicts, distress and challenges faced by psychotherapists after losing a patient to completed suicide and to examine the role of a self-compassion-based self-help intervention program, in facilitating healthy grieving and meaning making, learning processes.

Objectives

To understand the conflicts, distresses and challenges, faced by psychotherapists, after having lost a patient to completed suicide. To assess the efficacy of a self-compassion-based self-help interventions program, in navigating silent mourning and facilitating healthy grieving.

METHODS

Research Design

Single Case study Method

Procedure

A psychotherapist’s experience of losing a patient to suicide was selected for psychological workup and a self-compassion-based self-help Intervention plan was designed for addressing the associated psychological distress. A supervisor was contacted for monitoring the process and maintaining the objectivity. Self-compassion scale (short form) was utilized to assess the therapist’s level of self-compassion, Visual Analog Scale was used to mark the therapist’s distress experience and various written scripts like self-compassionate journals, letters, self-compassionate talk exercises, mood and thought logs which were part of the proposed intervention plan, were also utilized for assessing the progress. All these tools were self-administered before the intervention, followed by a post intervention assessment, conducted after two months of self-administering the intervention, on a daily basis. The results of the pre and post intervention were then compared with the help of qualitative analysis. A narrative analysis capturing the depth of the therapist's psychological world was performed and the emerging themes and insights were discussed with the relevant literature in the field.

Tools

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

For the purpose of analyzing distress experienced by the therapist, a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0, meaning- no significant distress related to the event, and 10, meaning- extreme distress related to the event, was utilized.

Self-compassion Scale (Short form) [13]

The scale was used to assess self-compassion in the therapist. This scale consists of 12 items. The original version of self-compassion scale assesses three dimensions of self-compassion and also gave the sub-dimension scores along with a full score, the short scale however, only gives a full score. As per the authors the short form has a near perfect correlation with the original scale. This scale is based on a likert type scale where individuals rate each statement from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always) based on its suitability.

Scripts

Consisted of self-compassion journals, letters, self-compassionate talk exercises, mood and thought logs.

CASE

Ms. X, licensed clinical psychologist, practicing for 6 years approached her doctoral degree supervisor, she had a good rapport with. Ms. X was maintaining well till 2 weeks before the incident. However, she reported feeling emotionally uncomfortable for over 2 weeks since she got the news of losing one of her therapy patients to suicide, whom she had been treating for 3 years.

She reported that the patient was a known case of bipolar affective disorder for the past 10 years with frequent mood fluctuations, severe socio-occupational dysfunction and disturbed family relationships. She reported that initially the patient manifested some resistance. However, she was gradually able to build a good rapport and healthy therapeutic alliance with the patient and after about 7 months of intensive individual, group and family therapy sessions, clinically significant changes were observed in the patient’s condition. He had become more compliant, developed smoother relationships with the family, had a structured daily routine, helped with the household chores and worked on his weight management. After 1.5 years of therapy his medication was significantly reduced and the desired stability was achieved in his mood symptoms. After 2 years, the patient started a business with the help of his family and managed the occupational demands. He remained compliant with therapy, often discussing how therapy had changed his life and how he looked forward to living his life feeling both hopeful and gratified. He was on monthly follow-ups and booked sessions in between as and when needed. There never was a mention of thoughts of self-harm nor did the family ever report any such issues. His parents rather reported feeling relaxed and happy, for the first time in years. They always appreciated him for all his efforts, supported him as needed and provided him the opportunity to function independently. Three months back, the patient canceled an appointment at the last moment citing work-emergency and after that he constantly postponed booking an appointment. Following the general protocol, the therapist e-mailed him about 5 times and made a few phone calls. His response was that he was busy and would soon book an appointment. The therapist also called his mother, who reported that the patient was doing well. Ms. X insisted that the family keep a close watch over the patient's compliance, mood and behavior. 2 weeks back, Ms. X received a phone call from the patient's mother. The patient’s mother was weeping bitterly and told Ms. X that the patient had committed suicide, the night before. Howling, she said to Ms. X, “You gave us these beautiful 3 years, only if we could have met you, it wouldn't have happened, thank you for taking care of our son so nicely, you gave him another life, he really respected you a lot, he listened to you, believed in you but he is no more”. Patient’s mother then mentioned that when they look retrospectively, they realize how the patient was preparing for his parting in the last few weeks, as he had contacted his old friends, had bought presents for and wrote letters to his family members, expressing love and gratitude for their efforts and apologizing for his mistakes. Ms. X reported feeling an overpowering sense of loss, doom and a chaos of feelings that seemed to paralyze her which forced her to cancel all her therapy sessions for the day. She reported that the words of the patient about how therapy had helped him look forward to living a life, the importance of the therapeutic relationship, how his parents believed in the therapist and conversation with the patient's mother about, “therapy giving him 3 years and therapy could have saved him,” made her feel that she could have saved this loss, etc., started reverberating in her mind. The realization that the patient had a plan of self-harm and that he connected with everyone else but the therapist, in the last few months fueled her mental agony. Ms. X felt betrayed and criticized herself for not picking up the clues and also not pushing the patient enough to fix an appointment. The therapist could see this loss affecting her overall wellbeing as she canceled appointments for three consecutive days. She also felt that she wasn't good enough for this profession and was full of self-doubts. Finally, she decided to reach out to friends and clinical supervisors. People were kind enough to offer space but the support offered, did not seem to help. The support extended, majorly involved one of the few responses 1) Reassurances like “you did your best”, “suicide was inevitable,” “no one could have done anything”, “you gave him a good life for three years” etc. These reassurances made the therapist question the contrast between the two statements; you gave him 3 years and you could not have saved him. The therapist had an understanding that the patient deliberately did not come for therapy, as he suspected that a therapeutic intervention would disrupt his suicidal plan and so she believed that some effort from the therapist’s side could have saved the loss. 2). She was told to learn “how to switch off from work” and that “it was just a patient”. Questions were raised on her professional training and competence as a therapist, her fitness for the profession and her emotional intelligence for feeling so upset for losing a therapy patient. She was advised to maintain boundaries between personal and professional life. Ms. X reported that these responses added to her self-doubts about professional competence, quality of her client interactions and her emotional fitness for the job. She also reported feeling torn between these remarks and her fundamental work ethics and understanding, which was- “every life matter,” “therapists deal with human material and so cannot take it lightly” “therapists deal with humans and their identities can’t be narrowed down to just being patients” and that therapeutic alliance is the base for therapy and it is engaging emotionally, cognitively and behaviorally for both, the patient and the therapist. These interactions did not allow mourning, forced speedy dissociation and indifference towards the event, trivialized the sorrow and offered reassurances that did not seem to help.

Ms. X stated that the experience was extremely isolating as she felt she was not understood and it was a loss that had a range of professional and personal implications. Moreover, the loss could not be discussed freely with family and non-professionals outside the professional community as it involved confidentiality concerns. It was very different from mourning a personal loss, where there is usually enough space and social support to grieve. This was mourning but in silence, which only seemed to complicate the already existing emotional chaos.

Ms. X reported that she was not feeling understood in the professional community and was aware of her emotional health. She associated it with socio-occupational distress and so she decided to engage in bibliotherapy. She engaged herself in reviewing some literature on the topic and tried to gain perspectives from self-reports and research articles on the topic. While on this journey, she discovered how some other mental health professionals who had suffered a similar loss, felt. She also found texts that emphasized the healing potential of self-compassion.

Ms. X then reached out to her doctoral supervisor for formal monitoring of her symptoms and a self-compassion-based self-help intervention plan. The supervisor agreed to monitor Ms. X’s self-help therapeutic journey and to provide objective feedback. The supervisor assessed Ms. X and ruled out clinical depression, anxiety, history of any other psychiatric diagnosis or significant psychological problem. The supervisor also analyzed the premorbid functioning of Ms. X, which was found to be adequate in all the life spheres-personal, social, emotional, occupational and spiritual. The supervisor even pointed out that Ms. X’s psychological abilities to emotionally connect with her patients, accept her own emotional discomfort, reach out for help and help herself when needed, manifested her emotional stability. Ms. X planned to decrease her caseload for the next two months and work on herself. The interventions seemed to gradually put things into perspective and facilitate recovery.

The Self-compassion-based self-help Intervention Plan for Navigating Silent Mourning

Following are the various components of the self-compassion-based self-help intervention plan utilized for effectively navigating through silent mourning. The components are not stepping but rather a list of the predominant and crucial aspects of the intervention.

Researching & Reading Texts on the Topic or Bibliotherapy

Silent mourning is a solitary experience. As the nature of experienced loss and grief were very personal and difficult for the therapist to communicate, it turned into silent mourning which alienated her from the world and left her with a sense of inadequacy, not only for not doing enough but also for feeling too much, as she was repeatedly questioned for “Grieving so much for a patient”. These cognitive and emotional aspects only complicated the grief and prolonged the trauma. Reading texts and reviewing articles on the topic helped the therapist feel less isolated as she found that other therapists who had experienced loss of clients reported feeling and thinking in similar ways. It gave her a perspective that she was not alone and that her emotions weren't necessarily “too much” and probably valid. This step was based on one of the three main facets of self-compassion-Isolation versus common humanity.

Allowing a Non-judgmental Space for Self to Feel, Mourn and Grieve

This space was created for the therapist to allow herself a humanizing experience. This was supposed to let her connect with her emotions without any judgment and restrictions as also to feel and validate the feelings beyond the consideration of right and wrong. It gave her an opportunity to observe the complexity of difficult emotions and slowly allow the capacity to look at them objectively and thus sit with them with decreasing discomfort. Brown [14] in her shame resilience theory appreciated the crucial role of a non-judgmental attitude while looking inwards. This exercise involved sitting with one’s thoughts without judgment and writing them down, as such. The time spent on this exercise differed on a daily basis but typically the exercise took about 20-60 min.

Self-Compassionate Mindful Exercises

Self-compassionate mindful exercises, like self-compassion guided meditation, breath work, self-compassionate touch and here- and- now were planned to be practiced on a daily basis. This was based on the premise of the other component of self-compassion- Mindfulness. As per Neff [10], mindfulness has the capacity to keep one grounded during a crisis. She recognizes that an adverse event can overwhelm an individual, affecting their ability to be rational and respond effectively. Mindfulness can restore the emotional balance and bring back the logicality through translating into healthy behaviors and assisting in desirable adjustment. These exercises were usually performed in the mornings for about 20-30 min to tone up for the day.

Self-Compassionate Talk, Eliminating Demeaning Words & Utilizing the Concept of “Double Standards”

Self-Talk is a very important component of one’s psychological world. It depicts one’s thought processes, emotional regulations and behavioral patterns. Thus, the impact of self-talk on one’s emotional health can’t be emphasized enough. Brown [14] and Neff [10], have consistently emphasized the role of self-compassionate talk, for overall well- being. Self-compassionate talk consists of conscious efforts to minimize self-critical and harsh comments and to apologize to oneself, if caught using any negative remarks. This also involves utilizing the concept of double standards, where one tries to objectively see as to what one is going through and how one would talk to a dear friend or a significant other if they too were going through similar situations. This practice, shed light on people’s tendency to be harsher and critically biased towards themselves, in situations during which they’d be far more compassionate towards others. Thus, an understanding was drawn that one is deserving enough of self-compassion if they can objectively extend it to others amidst the same circumstances. To encourage this, exercises in terms of self-compassionate letter writing, journaling, self-compassionate statements and quotes as cues were introduced to be performed regularly at least once a day, whenever the self-talk was found to derail from the track.

Self-Compassionate Acceptance of Oneself & Harnessing Authenticity

This involves acceptance of one’s own self with all emotions, thoughts, values and experiences. The purpose is to look at oneself as a whole, while acknowledging one’s strengths and limitations and allowing oneself the space to experience the range of human emotions including sadness, shame, guilt and anger while also embracing the values and beliefs one holds close to one’s heart. For this, written exercises and verbal self-affirmations were utilized. This fostered a sense of authenticity and the ability to nurture it further.

Compassionate Enquiry of One’s Fitness for the Job

To address the doubts regarding one’s fitness for the job, a structured compassionate enquiry was conducted. This involved compassionate inquiry regarding one’s values, work competence, motivation and interest, analyzing previous records of cases along with feedback. This inquiry deepened the therapist's understanding of her relationship with the profession, her past case works and the way she’d wanted to shape her future assignments.

Self-Compassion Directed Forgiveness for Self & Guilt Repair- A journey from Mistakes to Learning

This was, a conscious step by step attempt, to lighten oneself from the shame, guilt and anger directed at one’s self after the completed suicide of her patient. The therapist engaged in objectively analyzing the situation, identifying the biased thinking and blaming and recognizing what could have been done differently, through learning and engaging in a meaning making process. This paved the way for growth and development as a person and as a professional.

Self-Compassionate Boundaries to Protect One’s Values from Judgement

Self-Compassionate boundaries offer a space to protect one’s belief systems, values and emotional experiences without letting the judgment of other people contaminate them. It was especially useful in reconsolidating one’s primary work ethics and standard of care, which were held very high and followed with as much precision as possible. This exercise liberated one from the opinions of those who had a different worldview. The therapist, after a lot of thinking and reviewing feedback from her old patients, felt that her grounding work ethics were what made her who she was, as a professional and harnessed her to work for the better and that she could not let it go off, if she had to continue with her practice. She, however, did recognize a few areas which needed calibration of expectations from herself, as a professional.

Self-Compassionate Acceptance of Oneself, “As Only A Human, with Limited Control”

This exercise involved building one’s understanding of, “limited control,”, even as a professional and working with a realization that one is after all, only a human being. As a professional, one has the ability to assist others but there are functional limitations for everyone, which simply make us all human. This exercise brought self-awareness in terms of need for control and facilitated a liberation from extra responsibilities and expectations as a therapist. She regularly practiced self-talk in front of the mirror about how she can only do what's within her reach and how she can become more efficient with that. The self-talk also involved a component of accepting unpredictability. This self-talk was generally practiced before she began with her OPD every day.

Gratitude and Graceful Remembrance of the Lost Association

Gratitude and Graceful remembrance are a form of self-compassion. It is about appreciating what one has and letting go of the tapered view of the situations. In this way, one can make space for processing unhealthy emotions, allowing desirable experiences and fostering overall wellbeing. This exercise involves remembering the therapeutic alliance with gratitude and thanking the association for the learning and experiences it brought along with it. This was to counter the narrowed focus on this case that developed after the incident and revolved only around the completed suicide of the patient. The therapist also reached out to the patient's parents and had a conversation with them, reminiscing his good memories, offered support to the family and continues to see them to date, for their mental health concerns. Thus, this graceful remembrance brought back a bigger picture into the perspective and also facilitated the chance to connect with those who were grieving the same loss and even helped to develop mutual support as well as restoration of the alliance with the family.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Qualitative analysis was used to analyze the data. Narrative analysis was performed and the emerging themes were discussed. Findings of the study are presented under two sections: 1). Description conflicts, distresses and challenges faced by psychotherapist after losing the patient to completed suicide and 2). Discussion of the efficacy of self-compassion-based self-help interventions program in navigating silent mourning and facilitating healthy grieving.

Conflicts, Distresses and Challenges Faced by Psychotherapists after Losing a Patient to Completed Suicide, Possible Predictors of Severe Distress and Prolonged Trauma

Solitary Nature of Silent Mourning

Loss of a patient to suicide is an extremely personal experience for a therapist as it is dependent upon a host of factors. The loss is difficult to fathom for others. The nature of the loss is also professional which demands confidentiality and cannot be discussed with non- professionals, friends or family. Professionals, if not like minded, may also not be able to offer desirable understanding and support. Mourning personal losses with social support is a common and crucial process for healing and a therapist, silently grieving the loss of a patient to suicide, is devoid of this kind of support while dealing with probably the most challenging crises of their career. The isolation further complicates the situation and prolongs the trauma.

Nature of Therapeutic Alliance

Long term, healthy therapeutic alliance, based on mutual respect, collaborative approach, patient’s ability to understand the nature of illness, reaching out in times of need, compliance to treatment and improving course of illness are generally predictors of patient improvement and decreased risk for self-harm and suicidal behaviors [15]. In psychotherapy, the quality of therapeutic alliance has often been associated with suicidal behaviors in high suicidal risk patients and a healthy alliance between the therapist and the patient, is considered crucial for preventing self-harm or suicidal behaviors in the patients [16]. Thus, patient suicide in the presence of a healthy long-term therapeutic alliance is relatively more shocking and destabilizing for a therapist. Therapists share a professional yet intimate relationship with their patients. The duration and quality of therapeutic alliance, quality of therapeutic interactions, therapist’s relationship with the family and patient improvement can all affect the gravity of shock, loss, grief and trauma following the patient’s suicide.

Individual Factors

One’s personality, work ethics and values could also be important predictors of distress severity, in the therapists. Therapists with work ethic prioritizing patient care and wellbeing, assuming the role and responsibility of an assistant to help the patient, achieve better health outcomes, focused on forming and valuing therapeutic alliance with individual patients. Internal locus of control and questioning, “what did I miss,” may be more prone to him for experiencing prolonged distress. Wurst [17] noted a gender difference as a predictor of therapist distress, post the completed suicide of a patient. He found that more female therapists than males suffered acute emotional consequences. This was corroborated by Grad [5] who reported that women were more likely to experience shame, guilt and self-doubt. This can be interpreted with regard to the need to nurture a better capacity to feel emotional empathy in females.

Preparedness for unexpected crises, Role of Supervision & Training

Brown [18] noticed wide ranging hazards of a patient’s suicide for therapists, especially for those in training. Menninger [3] proposed that though patient suicides are not uncommon in psychiatric settings, they are often not a regular part of a mental health professional’s life and often an ignored part of their training curriculum. Kolodny [8] emphasized the role of crisis preparedness as an integral part of the mental health care professional’s training along with helping to facilitate effective support and supervision for processing grief and fostering feelings of growth and mastery. The potential of indirect trauma for therapists is well known but there still is a dearth of literature exploring the aftermath of the direct trauma of a patient’s suicide and very little clinical attention has been paid on developing a pathway to recovery for therapists who are survivors of patient suicides.

False Reassurances, Questioning Professional Competence of the Therapist and Forced Recovery

Reassurance is often the most prominently utilized psychological soother for anyone experiencing an emotional upheaval. Like any other technique, regardless of its scope of applicability, the context, communication and contradiction, need to be analyzed before intervening. Reassurance, like any other interventional methods, if introduced in the middle of the expression of the loss, can become a barrier to catharsis. A reassurance, not addressing the specific concerns of the griever and rather based on the lines of helper’s perspective won't align with him (the griever) and thus may not even be acceptable. False assurances, are quick conclusive remarks, in the absence of an adequate inquiry into the situation, intended to offer immediate psychological relief to the sufferers. These kinds of reassurances may either provide temporary relaxation or simply stimulate distrust in the sufferers about the interest, investment, bias and even credibility of the helpers. Hendin [4] found that false reassurances and interactions with colleagues did not relieve the distress of the therapists who had lost a patient to suicide. Another important factor that can add to the trauma of the therapist grieving the loss of a patient to suicide is raising doubts about the therapist’s professional competence for not snapping out of the loss. Menninger [3] pointed out that unlike other medical professions, the death of a patient due to suicide, is often interpreted as a professional failure or inadequacy on the part of the therapist and thus has potential to invoke far more complicated responses. Doubts on one’s professional abilities, questioning one’s fitness for the job, constant ruminations around one’s mistakes or possible contribution in patient’s suicide are the most frequently reported psychological sequelae following a patient’s suicide. Thus, responses questioning the therapist's proficiency can add to one’s trauma and might further isolate the professional, complicating the grief. Forcing recovery can cause emotional damage, a crucial step of healing from the loss of a patient, that is, permitting oneself to grieve. Alexander [19] pointed out the need for the therapists to allow themselves adequate time and space to mourn the loss. Gorkin [20] highlighted the role of unhealed pain from a patient’s suicide in pathological developments for therapists.

Role of the efficacy of self-compassion-based self-help interventions program in navigating silent mourning and facilitating healthy grieving

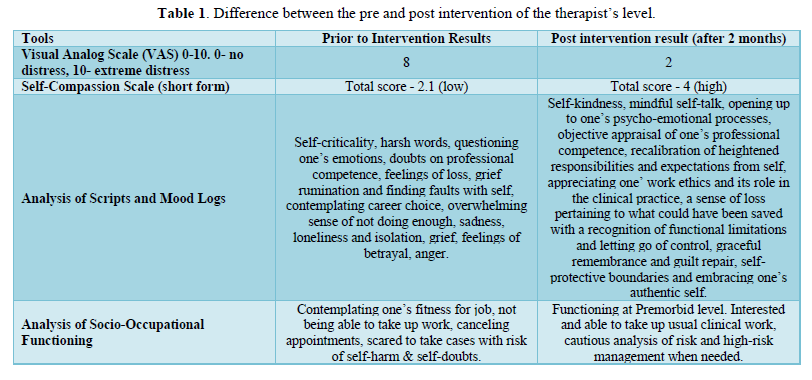

The following table details the difference between the pre and post intervention of the therapist’s level of self-compassion, experience of distress, description of thoughts and mood and socio-occupational functioning (Table 1).

Self-Compassion Intervention Efficacy

The above table depicts the changes in the mental health of the therapist pre and post self-compassion-based self-help intervention. Marshall [21] proposed the importance of a structured process for assisting therapists who had suffered the loss of a patient to suicide. This process emphasized the role of thorough expressions of feelings and experiences associated with the event, developing alongside an understanding of the factors contributing to suicide. Gorkin [20] stressed that the therapist must engage in a grieving process and readjustment, post losing a patient to suicide and elaborated the role of self-assisted and others assisted healing. Valente [22] elaborated the role of bereavement theories in understanding and formulating assistive intervention programs for healthy grieving and recovery of therapists mourning the loss of a patient. Horn [23] counted effective personal and professional support with post suicide review as crucial for facilitating healing from the trauma. Hendin [4] emphasized the therapeutic value of structured analysis of emotional experiences with a neutral group considering self-compassion as a broad concept with extensive research and far reaching implications for mental wellness. It is a learnable skill that offers a better alternative to self-esteem, which usually goes low as an individual is hit by an ego threatening circumstance [10]. Self-compassion has repeatedly been shown to be a promising buffer against trauma, depression, anxiety, grief and bereavement, stemming from catastrophic life events [24-27].

Psychologists often report high occupational stress, owing to the nature of the job, client engagement, crises cases, responsibility, compassion fatigue, burnout etc. Self-compassion-based training can help the professionals restore their wellbeing [28].

Mindfulness has been shown to assist in better handling of stressors [24]. Thus, a self-compassion-based training can harness mindfulness in the therapists, equipping them to mitigate daily life hassles and crises events. Self-compassion can also be utilized to introduce preparedness for unforeseen crisis events like suicide of a patient, which is sudden and often lacks closure being a potential source for grief ruminations. Lenferink [29] demonstrated the role of self-compassion as an effective mechanism that can lessen the preoccupation with finding closure related to causes and consequences of abrupt loss and thereby decreasing emotional distress. Self-compassion has also been shown to lower the severity of complicated grief related symptoms. Vara [30] suggested healing and desirable recovery from the complex process of silent mourning in therapists, following patient suicide. Self-compassion can help individuals look at themselves from a non- judgemental stance for increasing their abilities to embrace themselves with their strengths and limitations which have a more realistic perspective to see oneself as only a human, unburdening the sense of excessive responsibility and calibration of expectations from self. This can mediate the individuals' psycho-biological defensive response to social judgment, thereby protecting them from chronic anxiety (physical and biological, which has implications for aging and diseases) arising from social evaluation [31]. This has implications for psychotherapeutic training as individuals can build self-compassionate protective boundaries for themselves that could act like a barrier against undeserved and uncalled for judgements by others about their professional competence, work ethics etc. Self-compassion can also be used to build resilience in therapists so that they can remain afloat during the testing times, foster an approach to be kind to oneself, recognize the difficulties as part of human experience, patiently handle the adversities and move towards growth and mastery [32]. Guilt is a common emotion experienced by therapists who are survivors of patient suicide. Self-compassion can assist in trauma related guilt repair and in the absence of a therapist, self-administered worksheets, books and assignments can prove as effective interventions for self-assisted recovery [12].

LIMITATION, IMPLICATIONS & FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This paper utilizes the single case study method with sample (n=1). It, however, is both a limitation as well as a source of inspiration to pursue future work, in this direction. Losing a patient to suicide is sparingly traumatic, yet a common experience associated with a wide range of consequences. This paper attempts to emphasize the need to acknowledge the gravity of such trauma, formulate desired training and supervision programs, facilitate clinically useful interventions and bridge the gap in scientific literature by initiating a very significant yet unattended area of work.

The findings reiterate the importance of the practice popular in the psychodynamic school of psychotherapy, where therapists are required to attend therapy sessions in order to maintain their own wellbeing. It also stresses on the need for training programs that prepare and equip the aspiring psychotherapists to deal with the uncertainties of the profession, especially the ones relating to a patient’s suicide, while also emphasizing the need for quality supervision for practicing psychotherapists. Future research could be directed at exploring the nature of grieving, and the gravity of trauma among psychotherapists, associated with the suicide of their therapy patients. Researchers could also focus on understanding the relationship among the distress experience of post patient suicide, therapist personality, gender, years of experience etc. while utilizing a more structured methodology. This knowledge can help in formulating a more effective training program for psychotherapists as also assist in designing interventions that could assist therapists, grieving the loss of their patients.

CONCLUSION

Losing a patient to suicide is a potentially hazardous event in a therapist’s life. The sense of loss in the absence of a healthy coping mechanism, desirable support and healing environment can be alienating which can complicate the experience of loss. Self-compassion is a comprehensive intervention for overall wellbeing and can mediate the therapist’s distress followed by the patient’s completed suicide. There is a widespread significance of self-compassion-based self-help interventions in the training and supervision of psychotherapists to better equip them for professional catastrophes and promote resilience in them.

- Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, Torigoe RY, Kinney B (1988) Patient suicide: Frequency and impact on psychologists. Prof Psychol Res Pract 19(4): 416.

- Chemtob CM, Bauer GB, Hamada RS, Pelowski SR, Muraoka MY (1989) Patient suicide: Occupational hazard for psychologists and psychiatrists. Prof Psychol Res Pract 20(5): 294.

- Menninger WW (1991) Patient suicide and its impact on the psychotherapist. Bull Menninger Clin 55(2): 216.

- Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, Haas AP, Wynecoop S (2000) Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 157(12): 2022-2027.

- Grad OT, Zavasnik A, Groleger U (1997) Suicide of a patient: Gender differences in bereavement reactions of therapists. Suicide Life Threat Behav 27(4): 379-386.

- Wurst FM, Kunz I, Skipper G, Wolfersdorf M, Beine KH, et al. (2013) How therapists react to patient's suicide: Findings and consequences for health care professionals' wellbeing. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35(5): 565-570.

- Goldstein LS, Buongiorno PA (1984) Psychotherapists as suicide survivors. Am J Psychother 38(3): 392-398.

- Kolodny S, Binder RL, Bronstein AA, Friend RL (1979) The working through of patients' suicides by four therapists. Suicide Life Threat Behav 9(1): 33-46.

- Brown B (2010) The gifts of imperfection: Let go of who you think you're supposed to be and embrace who you are. Hazelden Publishing.

- Neff KD (2012) The science of self-compassion. Compassion Wisdom Psychother 1: 79-92.

- Cousineau T (2018) The Kindness Cure: How the Science of Compassion Can Heal Your Heart and Your World. New Harbinger Publications.

- Held P, Owens GP (2015) Effects of self‐compassion workbook training on trauma‐related guilt in a sample of homeless veterans: A pilot study. J Clin Psychol 71(6): 513-526.

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D (2011) Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 18: 250-255.

- Brown B (2006) Shame resilience theory: A grounded theory study on women and shame. Fam Soc 87(1): 43-52.

- Nafisi N, Stanley B (2007) Developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance with self‐injuring patients. J Clin Psychol 63(11): 1069-1079.

- Dunster-Page C, Haddock G, Wainwright L, Berry K (2017) The relationship between therapeutic alliance and patient's suicidal thoughts, self-harming behaviors and suicide attempts: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 223: 165-174.

- Wurst FM, Mueller S, Petitjean S, Euler S, Thon N, et al. (2010) Patient suicide: A survey of therapists' reactions. Suicide Life Threat Behav 40(4): 328-336.

- Brown HN (1987) The impact of suicide on therapists in training. Compr Psychiatry 28(2): 101-112.

- Alexander P (1977) A psychotherapist's reaction to his patient's death. Suicide Life Threat Behav 7(4): 203-210.

- Gorkin M (1985) On the suicide of one's patient. Bull Menninger Clin 49(1): 1.

- Marshall KA (1980) When a patient commits suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 10(1): 29-40.

- Valente SM (1994) Psychotherapist reactions to the suicide of a patient. Am J Orthopsychiatry 64(4): 614-621.

- Horn PJ (1994) Therapists' psychological adaptation to client suicide. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train 31(1): 190.

- Hall CW, Row KA, Wuensch KL, Godley KR (2013) The role of self-compassion in physical and psychological well-being. J Psychol 147(4): 311-323.

- Zessin U, Dickhäuser O, Garbade S (2015) The relationship between self‐compassion and well‐being: A meta‐analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well‐Being 7(3): 340-364.

- Winders SJ, Murphy O, Looney K, O'Reilly G (2020) Self‐compassion, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother 27(3): 300-329.

- Zeller M, Yuval K, Nitzan-Assayag Y, Bernstein A (2015) Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43(4): 645-653.

- Finlay-Jones AL, Rees CS, Kane RT (2015) Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: Testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PLoS One 10(7): e0133481.

- Lenferink LIM, Eisma MC, de Keijser J, Boelen PA (2017) Grief rumination mediates the association between self-compassion and psychopathology in relatives of missing persons. Eur J Psychotraumatol 8(sup6): 1378052.

- Vara H, Thimm JC (2020) Associations between self-compassion and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved individuals: An exploratory study. Nordic Psychol 72(3): 235-247.

- Arch JJ, Brown KW, Dean DJ, Landy LN, Brown KD, et al. (2014) Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 42: 49-58.

- Scoglio AA, Rudat DA, Garvert D, Jarmolowski M, Jackso C, et al. (2018) Self-compassion and responses to trauma: The role of emotion regulation. J Interpers Violence 33(13): 2016-2036.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Nursing and Occupational Health (ISSN: 2640-0845)

- International Journal of Diabetes (ISSN: 2644-3031)

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- Archive of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine (ISSN:2640-2297)

- BioMed Research Journal (ISSN:2578-8892)

- Journal of Cancer Science and Treatment (ISSN:2641-7472)