Research Article

EFFECTS OF FLEXIBLE WORKING ARRANGEMENT ON JOB SATISFACTION

8484

Views & Citations7484

Likes & Shares

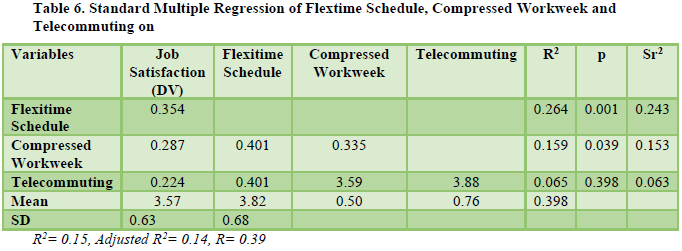

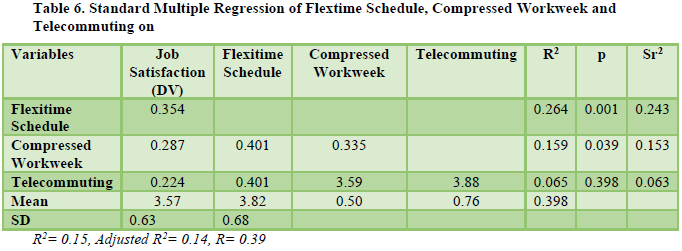

The rapid trend of changes and social issues in managing the global workforce have forced organizations to look for innovative ways of enhancing the job satisfaction of employees. Among these innovative approaches are provision of Flexible Working Arrangements (FWAs). The purpose of this exploratory research was to identify the effects of FWAs, i.e., flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting on job satisfaction from the perspective of the Ethiopian national employees of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) in Addis Ababa. To achieve this objective both descriptive and inferential statistics were conducted. The total population of the study was 250; out of which 71% responses were collected. A primary data collection method was implemented using a structured questionnaire. The analysis showed that there is significant positive effect of flextime schedule (R = 0.39, R2 = 0.264, p = 0.001) and compressed workweek (R = 0.39, R2 = 0.159, p =0.039). This means that increase in the use of flextime schedule and compressed workweek enhances job satisfaction for employees of the ECA in Addis Ababa. The independent variables reported R = 0.39 and R2 = 0.15 which means that 15% of corresponding variations in employee job satisfaction can be explained by flexible working arrangements. Nevertheless, this study found out that there is no significant relationship of telecommuting (R = 0.39, R2 = 0.065, p = 0.398) on job satisfaction. Therefore, since the provision of FWAs is at nascent stage, further studies on the effect of telecommuting on job satisfaction from Ethiopian employee’s context are highly recommended.

Keywords: Flexible working arrangement, Flextime schedule, Compressed workweek, Telecommuting, Job satisfaction, Un-ECA, Ethiopia.

INTRODUCTION

The fast-paced changes in the characteristics of global workforce and the seismic trend of approaches in managing human resources are forcing organizations to look for innovative strategies of attracting and retaining talents as well as motivating employees. The provision of employee-friendly policies or FWAs have been considered among these emerging innovative human resources management practices (Baard & Thomas, 2010; Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015; Ansong & Boateng, 2017; Lakshmi, Nigam & Mishra, 2017). This shift of mindset in incorporating FWAs as a means of organizational competitive advantage points to the fact that “work is no longer a place but what you do” (Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015).

The fast-paced changes in the characteristics of global workforce and the seismic trend of approaches in managing human resources are forcing organizations to look for innovative strategies of attracting and retaining talents as well as motivating employees. The provision of employee-friendly policies or FWAs have been considered among these emerging innovative human resources management practices (Baard & Thomas, 2010; Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015; Ansong & Boateng, 2017; Lakshmi, Nigam & Mishra, 2017). This shift of mindset in incorporating FWAs as a means of organizational competitive advantage points to the fact that “work is no longer a place but what you do” (Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015).

Taking into consideration the multifaceted benefits of FWAs, mainly in enhancing organizational productivity and employee satisfaction, its adoption and implementation have become a dominant issue in the workplace almost everywhere (Mungania, Waiganjo & Kihoro, 2016). Presently, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has placed FWAs in the spotlight. Employers everywhere including government agencies in Ethiopia and beyond, who may have not put in place such modality to offer flexible scheduling options, have been suddenly forced to implement flexible work options on the fly. For example, the Council of Ministers in Ethiopia has passed decisions on the federal government employees to work from home effective March 25, 2020 until further notice (FBC 2020). Even those organizations who have offered FWAs to their employees have never done so on a larger scale at all levels. FWAs have now become the new normal working modality (SHRM, 2020; Kim, Galinsky & Pal, 2020).

Most organizations from the public sector, private as well as non-profit making are adopting and implementing various forms of FWAs (Nijiru, Kiambati & Kamau, 2015; Waiganjo & Kihoro, 2016). The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) office in Ethiopia is one of these organizations that recognized the benefits of incorporating FWAs practices as an innovative human resources management approach. It has designed a policy for implementing the most common forms of FWAs. The Commission has already adopted FWAs way before the prevalent of the pandemic COVID-19 (UN HR Portal, 2015).

The three forms of FWAs, which are flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting, are the focus of this study. Flextime Schedule allows employees a certain level of autonomy to choose their start and end times provided that they work the required number of the daily compulsory hours. Several empirical studies show flextime schedule as one of the most widely used FWAs across organizations in enhancing employee motivation as well as increasing productivity (Opeyemi et al., 2019; Rahman, 2019; Waiganjo & Kihoro, 2016; Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016; SHRM, 2015; Dettmers, Kaiser & Fietze, 2013).

Compressed workweek is another form of scheduling practice–it allows employees to work a standard working hour compressed into fewer than five days in one week by increasing the number of hours an employee is required to work each day (SHRM, 2020; CRANET, 2005; Bird, 2020). Unlike these two provisions, telecommuting or telework is working away from a central workplace using technology to perform tasks. It provides location flexibility. Telecommuting is considered as the fastest growing mode of FWAs. Outcome of several empirical studies done in the developed world pointed out benefits of using these provisions such as enhancing job satisfaction and employee commitment, operating cost reduction and addressing social issues (improving road-conjunction, minimizing pollution (Cox, 2009; Alen, Gordern & Shockley, 2015; Ansong & Boating, 2017; Sitotaw, 2019).

In view of this, the study attempted to explore the effects of FWAs, i.e. flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting on the job satisfaction from the perspective of Ethiopian national employees of ECA in Addis Ababa, an organization established in 1958 to promote the economic and social development of its member States. In so doing, this study shades light in better understanding the effect of these most common forms of flexible working arrangements on job satisfaction from Ethiopian employees’ perspective.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Conceptualization and definition

The concept of FWAs as a human resources management practice was introduced in 1967 at a German Aerospace Company as a means to minimize absenteeism (Opeyemi et al., 2019). According to Opeyemi et.al, the introduction of FWAs from this period onwards has brought a complete turnaround in bringing more and more women in workplaces that has been previously dominated by men as a result of benefiting from flexible arrangements. The broad framework that guided the notion of FWAs in organizational setting is Jon Atkinson’s Flexible Firm model (a technique for organizing human resources using various forms of workplace flexibility) that was first proposed in 1986 (Dettmers, Kaiser & Fietze, 2013). Flexible working is now considered as smart working–one of the approaches that drive greater efficiency and effectiveness in achieving organizational goals by introducing new practices such as flextime and telecommuting which is different from the standard arrangement (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014).

Flexible working arrangement can be defined in different forms. It is a human resources management practice that allows employees of an organization in making informed choices about when, where and for how long they undertake work-related responsibilities (Opeyemi, et al., 2019). Flexible working arrangement is also defined as an “alternative work options that allow work to be accomplished outside of the traditional temporal and/or spatial boundaries of a standard workday” (Rau & Hyland, 2002). It refers to work arrangements not bound by physical confines of a traditional office location, it is rather the scheduling of work hours and workweeks not limited by spatial boarders. In this work pattern, employees are allowed to adjust their schedule and workplace. According to McGuire, Kenney & Brashler (2010), FWAs can be considered as “any one of a spectrum of work structures that alters the time and/or place that work gets done on a regular basis”.

General overview of flexible work arrangements Maintaining and retaining the right human talent is one of the key detrimental factors for organizational success. In this fast-paced era, adoption of human resources practices that enable organizations to adapt its workforce to changes in the working environment is now being given greater attention globally. Based on vast literature and empirical studies in human resources management, FWAs is one of these strategic approaches that are benefiting both organizations as well as employees in coping up with these challenges (Alen, Gorden & Shockley, 2015; Miller, 2016). Large bodies of studies denote that there are several benefits of FWAs (Opeyemi et al., 2019; Rahman, 2019; Omondi, & K’Obonyo, 2018; Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016; SHRM, 2015; Dettmers, Kaiser & Fietze, 2013; CRANET, 2006; Albion, 2004; Pruchno, Litchfield & Fried, 2020).

Most notably, FWAs do have leveraging benefits for reducing absenteeism, improving commitment, enhancing employee retention and increasing employee satisfaction (Rahman, 2019). According to a survey result by SHRM (2015), the study outcome on the positive impact of FWAs indicated job satisfaction (80%), enhancing quality of employees’ personal/family lives (84%) and employee health and wellness (52%). Moreover, based on a recent empirical study done in the U.S. on the use of FWAs before the coronavirus outbreak, majority of employees (51%) had access to more than three types of flexible scheduling options. The empirical study shows only 8% of employees did not have access to any options. And, more than 26% of them had access to five or more types of FWAs (Kim, Galinsky & Pal, 2020). Their study also showed the positive predictors of high job satisfaction as perceived scheduling flexibility, support for flexibility from supervisors and coworkers and support for healthy lifestyles. To cope up in this dynamic world, incorporating flexible working arrangement as one aspect of human resources management practice is now being considered as a bridge in aligning individual and organizational goals (Rahman, 2019). Therefore, adopting more flexible working options are believed to serve as an approach in attracting and retaining competent human capital.

Scholars also noted that workplace flexibility does not always imply family-friendly or employee-centered arrangements (Albion, 2004). Its success is highly dependent on a number of factors such as meeting the needs of both employees and employers, as well as effective communication to the employees on the benefits of such provisions. Results from empirical studies conclude that greater workplace flexibility is a win-win situation for organizations and their employees (Omondi & K’Obonyo, 2018; CRANET, 2006). It is also difficult to implement FWAs uniformly to all job types. As pointed out by Rahman, FWAs can only be effectively applied to certain jobs such as human resources, information management, counselling and so on (Rahman, 2019). Therefore, designing a companywide FWAs as well as ensuring effective and efficient use of FWAs call for strong support from organizational leaders as well as its proper institutionalization.

Categories of flexible working arrangements

FWAs are broadly categorized as schedule flexibility and location flexibility (SHRM, 2020). There are various types of FWAs that can be categorized as schedule flexibility and location flexibility. From organizational and employees’ perspectives as well as other factors such as, firms view of FWAs itself, the type of jobs and country context, organizations adopt various modalities of FWAs (SHRM, 2015). In order to make these flexibility options operational, some firms develop formal written policies that provide clear guidance to employees on such provisions (Jackson & Fransman, 2018); while others do not consider it as entitlements of employees rather managers of such organizations negotiate with individuals based on assessing performance factors (SHRM, 2015).

According to CRANET (2005), the FWAs yield better result for organizational effectiveness and performance when they are considered as bundles of arrangements. As a result, they categorize these practices into four different bundles. Namely: a) non-standard work patterns which include annual contracts, part-time work, job sharing, flextime,

fixed-term contracts, compressed workweek, b) non-standard work hours that are weekend work, shift work and overtime, c) work outsourced such as temporary employment and subcontracting and d) working away from the office which refers to home-based work and telecommuting. In view of CRANET, FWAs deal with work patters, work hr, work outsourced and work away from office. As identified by a number of other empirical studies, the three most common forms of FWAs that are in use by many organizations presently are flextime schedule, compressed work week and telecommuting (Opeyemi et al., 2019; Rahman, 2019; Waiganjo & Kihoro, 2016; Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016; SHRM, 2015; Dettmers, Kaiser & Fietze, 2013). Accordingly, this study only focuses on these three common categories of FWAs which are discussed in subsequent sections.

Flextime Schedule is broadly categorized under schedule flexibility practices (SHRM, 2020). As the name implies, this arrangement allows an employee to choose their start and end time by fulfilling two prior conditions, which are working the required number of hr per day and being at work during the core business hr of the day (Rahman, 2019). Core business hr refer to the daily compulsory hr that employees are at work. This arrangement including the extent of its variation is dependent within parameters given by firms, however there are common arrangements (Bird, 2010). For example, a certain company may have core hr between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm. Then employees might have the choice to start anytime between 7:00 am to 9:00 am and the choice to leave anytime between 4:30 pm to 6:30 pm, provided that they work 8 hours. Some employers also permit a carryover of hours within a fixed period by not requiring their employees that eight hours be completed each day - allowing the compensation of the balance any time in the future to meet the requirement of a forty-hr work week (Bird, 2010). Flextime schedule allows employers to operate beyond the conventional working hr as well as give employees a certain level of autonomy (Rahman, 2019; Jackson & Fransman, 2018).

Several empirical studies pointed out a number of benefits of flextime arrangements including its effect in improving commuting, improving productivity, improving work-life balance, increasing job satisfaction, reducing operating cost such as overtime payments and more (Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016). As indicated by Jackson & Fransman (2018), the association between flextime and job satisfaction from the context of developed countries is heavily researched and the most commonly reported in the literature (Jackson & Fransman, 2018). For example, empirical studies showed flextime as one of the most widely used FWAs across organization as well as the existence of positive relationship between flextime arrangement as independent variable and job satisfaction as dependent variable (Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016; Omondi & K’Obonyo, 2018; Rahman, 2019). Overall, there is a strong claim that workplace flexibility does lead to improved job satisfaction and morale among employees. Ronda, López and López (2016) and a number of other empirical studies pointed out that there is an obvious correlation between employers that are able to show trust and support for their employees (provision of flextime arrangement) and employees who are more satisfied with their job and those who work harder (Ronda, López & López, 2016; Rahman, 2019; Jackson & Fransman, 2018; SHRM, 2020).

The drawback of this practice is that “scheduling trainings and meetings can be very difficult while practicing flextime in the organization and there could be lack of supervision for those who work during nonconventional hours” (Scott & Rahman, 2019). This can create burden on managers in meeting the competing needs of their organizations as well as their co-workers. Moreover, such arrangement might not be practical to be implemented in continuous process operations such as manufacturing organizations–assembly lines (Baltes et al., 1999). Therefore, it is important to note that just having access to flextime provision, in and of itself, might not give the important outcomes that employers and employees care about such as productivity, job satisfaction, health and well-being.

Compressed workweek is another form of scheduling method that allows employees to work a standard workweek of 40 hours compressed into fewer than five days in one week (SHRM, 2020; CRANET, 2005). The concept of compressed workweek (the working modality of 4 days a week) became popular in 1970’s in which companies claimed great results and more businesses began to use them (Bird, 2010). According to Bird, ‘interest in compressed workweek [modality] peaked in 1973’ (Bird, 2010). In this scheduling, the workweek is reduced than the standard days by increasing the number of hours an employee is required to work each day. For example, instead of the standard five 8-hr days week, employees can work for four 10 hours days. In this modality, employees work fulltime in a few whereas longer days (Rahman, 2019; Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016).

The most common forms of compressed workweek is 4/40 - employees work 10 hours daily in 4 days of the week and they will be able to take either Friday or Monday off, enabling employees to extend their weekend to 3 days (Baltes & Sirabian, 2017; Baltes, et al. 1999; Njiru, Kiambati & Kamau, 2015). This arrangement entails ‘an extra day off in the middle of the week, a weekend work day with two weekdays off, or rotating days off to share the three-day weekend across the workforce’ (Bird, 2010). The recently introduced compressed week schedules that have been adopted by some organizations include 3/36, 4/32, and more, with employees working three days for twelve hr per day or four days for eight hr per day, respectively (Bird, 2020; Baltes et al., 1999). For example, most UN offices in Addis Ababa have implemented compressed workweek for many years by allowing their employees to work for 32 hours from Monday to Thursday (8:30 am to 1:00 pm and 2:00 pm to 5:30 pm) and only work for 5½ hours (8:30 am to 2:00 pm) on Fridays without lunch break. This arrangement allows employees to take Friday afternoons off.

There are prior considerations in implementing compressed workweek. Workweek can only be compressed in alignment with any federal law (if any) that caps the number of working hours. For example, in Germany the working day can be extended to 10 hours but the average daily working hours, within 6 months, should not exceed 8 hours (Baltes & Sirabian, 2017). Compressed workweek modality is not mentioned in Ethiopian labor law; however, the provision of the new Proclamation of article 67(2) does clearly indicate that the maximum overtime work is capped at 4 hours per day and a maximum of 12 hours per week (EFDR, 2019).

Compressed workweek is commonly used in manufacturing settings due to the interdependence nature of the work in assembly lines and the fact that manufacturing organizations might not require employees to be present at regular time intervals (Baltes & Sirabian, 2017; Baltes et al. 1999). Moreover, in comparison to other FWAs such as flextime and telecommuting, compressed workweek arrangement is claimed to be less desirable by employees (Rahman, 2019).

In view of a quantitative (meta-analysis) study done in 1999, compressed workweek is indicated to have positive relationship to both the job satisfaction and satisfaction with work schedule (Baltes et al. 1999). It is also asserted in this study that the key features of a job including responsibility, autonomy and job knowledge emanated from implementing compressed workweek might be related with more positive attitudes toward the job itself. Such positive changes would lead to higher job satisfaction. In view of this empirical study, the extent of behavioral work-related criteria such as absenteeism and productivity were lower than attitudinal work-related criteria such as job satisfaction when compared to the findings of flextime schedule. On the contrary, a recent study done in 2008 showed a positive relationship with productivity of employees working a 4/40 compressed week schedule but the finding reported that these employees did not have greater job satisfaction (Facer & Wadsworth, 2008).

In conclusion, compressed workweek allows employees to exercise certain form of autonomy in managing their time, it increases their job responsibility and knowledge which are positive indicators of employees’ attitude towards their job. And, these positive organizational outcomes are correlated with employee job satisfaction. As discussed above, the extent of the provision of compressed workweek on job satisfaction might be lower than that of flextime schedule. Nevertheless, compressed workweek schedule does positively affect employee job satisfaction.

Telecommuting

The terms telecommuting or telework are used interchangeably (Lakshmi, Nigam & Mishra, 2017; Huws, Jagger & O’Regan, 1999). Telecommuting is best defined as “a work practice that involves members of an organization substituting a portion of their typical work hours (ranging from a few hours per week to nearly full-time) to work away from a central workplace-typically principally from home-using technology to interact with others as needed to conduct work tasks” (Alen, Gordern & Shockley, 2015). The focus of telecommuting is on provision of location flexibility.

Another key aspect of telecommuting as identified by a number of literature and empirical studies is the advancement of information and communication technologies such as the spread of broadband services, mobile connections at ever-affordable rates that paved the way for telecommuting as the fastest growing mode of flexible work environment (Cox, 2009; Siddhartha & Malika, 2016; Ansong & Boateng, 2017). Moreover, the shift from manufacturing to information economy is the other factor which contributed for the increase of jobs that lend themselves to telecommuting (Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015). From the inception of the notion of telecommuting in 1973, a large number of organizations mainly in the developed countries have now adopting it as a mainstream organizational strategy to accessing work other than a central place of work. (Miller, 2016; Cox, 2009; Alen, Gordern & Shockley, 2015; Teh, et al., 2017).

A number of empirical studies unearthed key employee motivational factors that drive high organizational productivity from the implementation of telecommuting scheme (Cox, 2009; Ye, 2012; Teh et al., 2013; Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015; Ansong & Boateng, 2017). To mention a few, an outcome of an empirical study done in Malaysia among telecommuting employees identified job satisfaction and employee commitment as well as operating cost reduction as advantages of telecommuting (Baard & Thomas, 2010; Teh et al., 2017; Ansong & Boateng, 2017). Other empirical studies done on telecommuting showed work-life balance - one of the intrinsic motivational factors of Towers Perrin’s model (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014), as one of the main benefits of telecommuting (Baard & Thomas, 2010; Miller, 2016; Okoli, 2016; Dissanayake, 2017; Ansong & Boateng, 2017). Telecommuting also plays a significant role in addressing social issues in the form of improving road conjunction for countries with highly growing population by reducing work travel time or changing it out of the peak period, minimizing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015; Siddhartha & Malika, 2016; Okoli, 2016).

The assertion of these studies on the importance of telecommuting in terms of enhancing employee and organizational effectiveness as well as its positive impact on employee satisfaction and society in general points to the fact that “Telecommuting arrangements bring to the forefront the notion that work is no longer a place but what you do” (Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015).

Employee job satisfaction is a widely used, very well studied and measured term in the area of human resources management. Job satisfaction is now considered as a universal factor for all forms organization in determining employee and organizational productivity. Scholars also assert that the concept of job satisfaction can be seen in a number of ways. According to Spector (1997), job satisfaction refers as to what level people like about the various aspects of their job. Similarly, it can also be defined as individual’s state of pleasurable emotions in the form of having positive feeling or attitude about their career while performing at their workplaces (Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016). In view of Price (1997), job satisfaction refers to “the degree to which employees have a positive affective orientation towards employment by the organization.” It refers to an inner form of satisfaction that employees experience from the commonly distinguishing dimensions of job satisfaction such as the work itself, supervision, monetary rewards and coworkers (Price, 1997). From the viewpoint of humanitarian perspective, job satisfaction can be considered as a demonstration of benefiting from healthy working conditions as well as an indicator of the physical and psychological well-being of employees (Addis, Dvivedi & Beshah, 2018).

Among the sources of employee job satisfaction include FWAs, work climate or working conditions, employees’ ability to meet the demands of their family and personal lives (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014; Ivancevich & Matterson, 1997). Large body of empirical studies state that FWAs can benefit both the employers and the employees in terms of higher commitment, lower turnover, reduced work-family conflict and higher job satisfaction. Among these FWAs that make employees feel enriched include: flextime, compressed workweek and telecommuting (Rahman, 2019). These studies also pointed out the presence of positive relationship between FWAs and job satisfaction as employees maintain harmony within their family demands and job responsibilities (Rahman, 2019). Another study states that proper implementation of FWAs can result in higher job satisfaction due to employees’ provision to a certain level of autonomy in fulfilling both their personal and work lives (Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016).

Many scholars (Allen, 2001; McNall, Masuda & Nicklin, 2010; Maxwell et al., 2007; Allen, Golden & Shockley, 2015) identified that most of the independent variables such as flextime schedule, telecommuting and compressed workweek have greater influence on dependent variables such as job satisfaction, absenteeism and organizational productivity.

In summary, based on the studies of Rawashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber (2016) and Rahman (2019), many scholars in the practice of FWAs have pointed out on the positive relationship between the aforementioned three practices-flextime, telecommuting and compressed workweek as independent variables and other dependent variables such as job satisfaction, work-family balance, productivity and absenteeism. Based on the above literature review, the following research hypotheses were developed.

H1: There is a positive association of flextime schedule on job satisfaction

H2: There is a positive association of compressed workweek on job satisfaction

H3: There is a positive association of telecommuting on job satisfaction

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

A cross-sectional quantitative approach was used in exploring the effect of the three components of FWAs, i.e., flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting (independent variables), on job satisfaction (dependent variable). Since the study has more than two independent variables in continuous data type format and one dependent variable, multiple regression analysis was used (Pallant, 2001 & Creswell, 2009).

Rahman (2019), upon conducting similar empirical study, suggested that in order to obtain more accurate data, large number of respondents should be reached out. As a result, the researcher employed census method - studied the entire population that is 250. Specifically, relevant staffs from professional level, national officers and general support categories were considered as the study population.

A structured survey questionnaire with two sections were developed based on data from previous empirical studies. Section A comprises the components of FWAs i.e., flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting (the independent variables) and job satisfaction (the dependent variable). It was constructed in the form of likert-scale ranging from “1” (i.e., strongly disagree) to “5” (i.e., strongly agree). Section B focused on gathering demographic information of respondents (i.e., sex, age, job duration and position). The questionnaire in Section A had 20 items that was adopted with some modifications from prior studies of Rawashedh et.al. (2016) and Rahman (2019) on FWAs. This questionnaire was used as an instrument to measure both the independent and dependent variables.

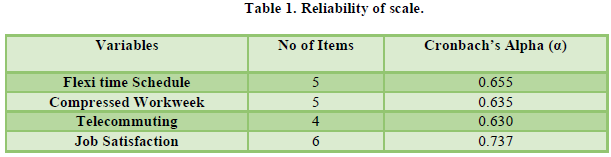

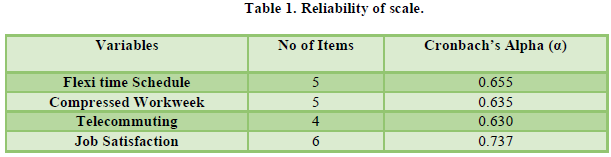

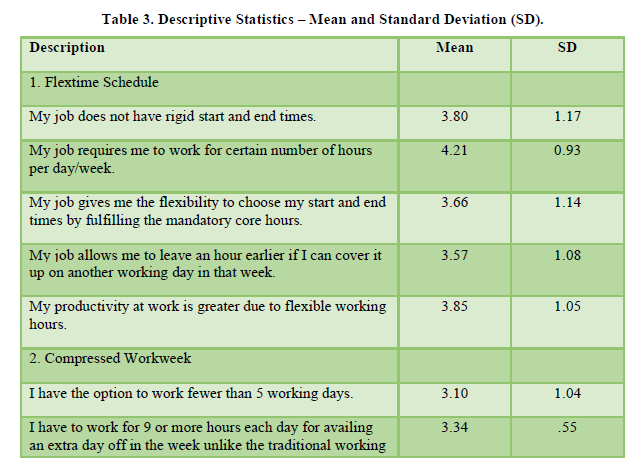

As shown in Table 1, scale reliability of constructs from statistical analysis of Mean and Standard Deviation of responses has been tested using Cronbach’s Alpha in order to examine the consistency between constructs of the survey instrument (Creswell, 2009).

Table 1 presents the reliability and validity test, which was conducted to measure the internal consistency among the four constructs of this study. Studies pointed out that there are no uniformly acceptable values of alpha (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011; Rahman, 2019). Based on these studies some indicate 0.70 to 0.95 while others denote 0.60 as the lowest acceptable value of alpha. Tavakol and Dennick stated that correlation of items in a test does imply an increased value of alpha but it does not always denote a high degree of internal consistency. They go on to explain that there are other factors such as the length of the test that can reduce the value of alpha. Moreover, according to Malhotra (2007) in Rahman (2019), “an Alpha (α) value of at least 0.60 can be considered to be acceptable where he suggested, the higher the score the greater will be the reliability of the data (Rahman, 2019)”.

The values of Alpha in this study are between 0.630 and 0.737. Based on the above explanation, all components fall within the acceptable range and it can be inferred that these items from the questionnaire are valid and be considered to be reliable for this study.

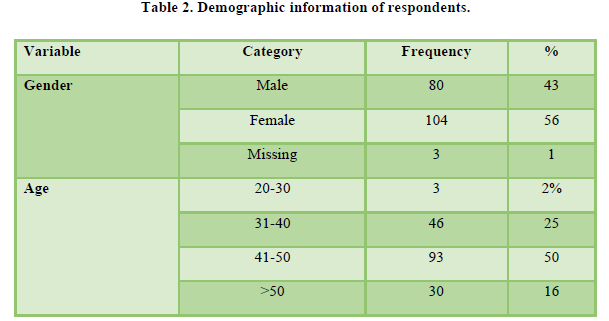

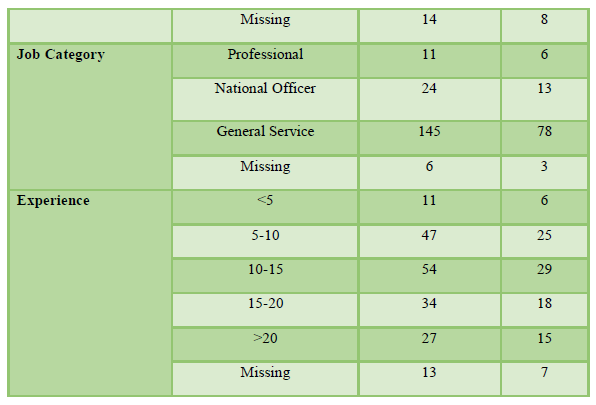

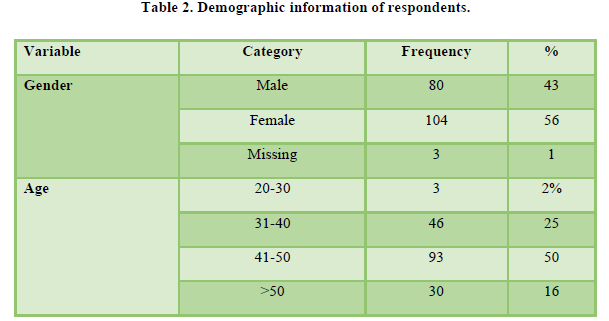

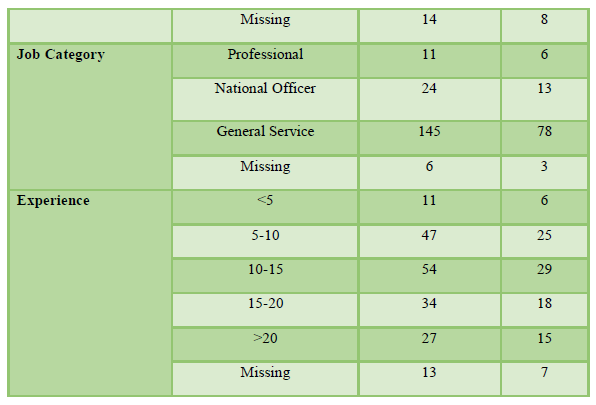

ANALYSIS

Out of the total questionnaires sent to 250 employees, 178 (71%) questionnaires were returned and used for the analysis. Majority of the respondents were female, i.e. 56%. Most of the respondents’ surveyed fall under the age of 41-50 as well as a noteworthy proportion of respondents are general service staff, i.e., 78%. When respondents were asked about their work experience, it has been found that 29% of them have been working in their current institution for 10 to 15 years, whereas only 6% of them have been working for less than 5 years, an indication of a low-level attrition.

Descriptive Analysis of the Variables

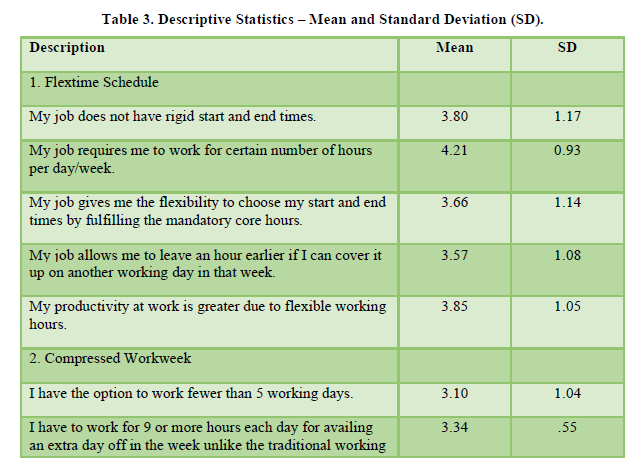

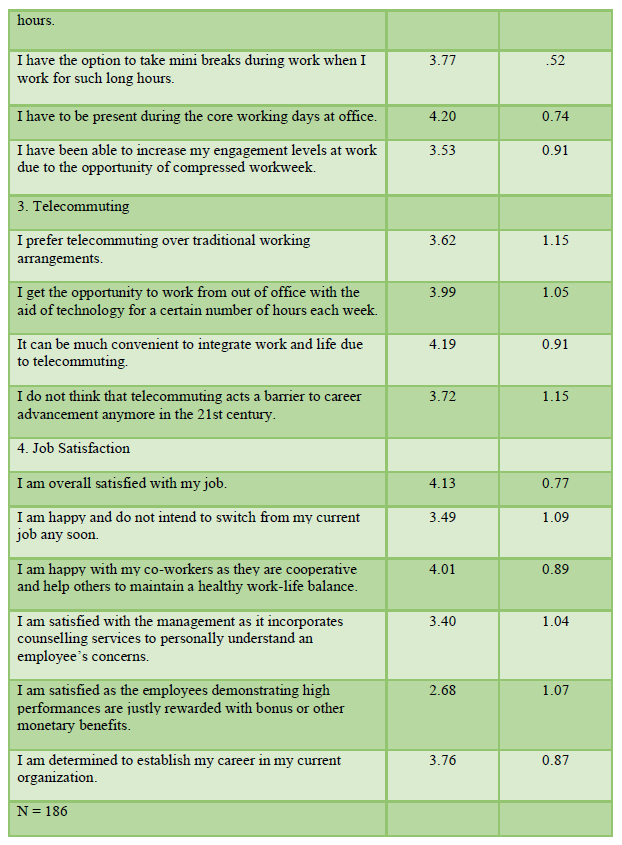

As shown in Table 2, the three components of FWA contain 14 questions that asked respondents to state their perception of each variable. Each of these independent variables, Flextime Schedule, Compressed Workweek and Telecommuting has 5, 5 and 4 items, respectively. The dependent variable, Job Satisfaction scale, has 6 items that measure the Job Satisfaction of the employees.

In view of this, Table 3 demonstrates the mean and standard deviation of these 20 variables. As can be noted, the mean values of 19 variables range from 3.10 to 4.21 which signifies the tendency of responses towards the scale of “Neutral” and “Strongly Agree”. The standard deviation of these 19 variables ranges between 1.15 to 0.74. Among the four factors of FWAs considered in this study, the mean values of the items under Flextime Schedule tend to be mostly higher than the values of the items under the Compressed Workweek and Telecommuting which is in alignment with prior studies of (Rahman, 2019; Rwashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016).

Regression analysis

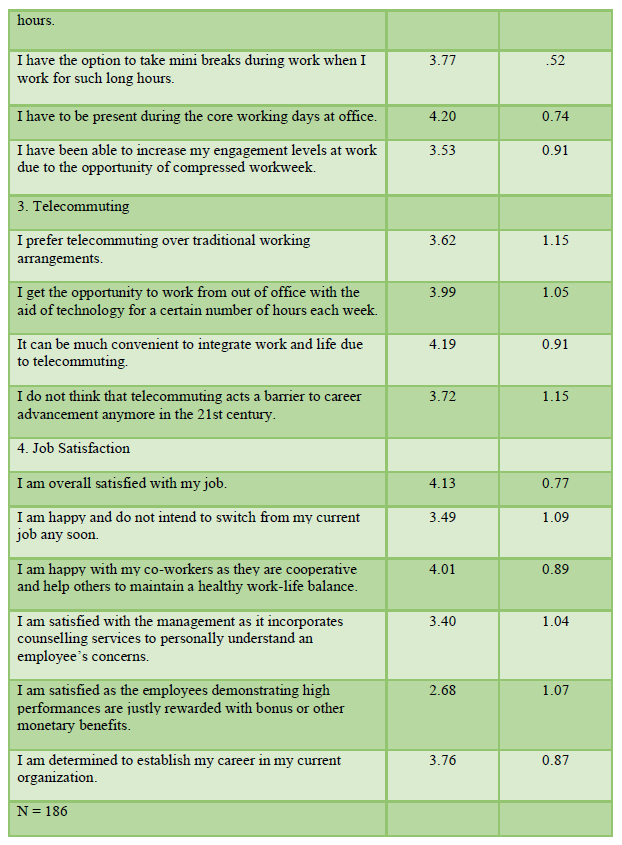

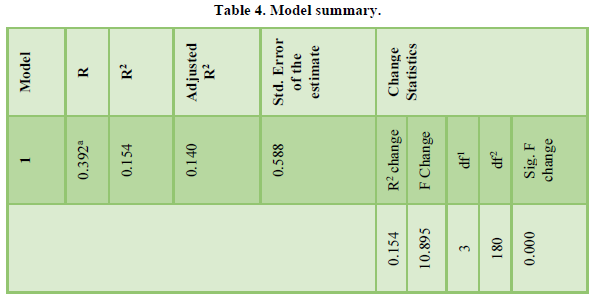

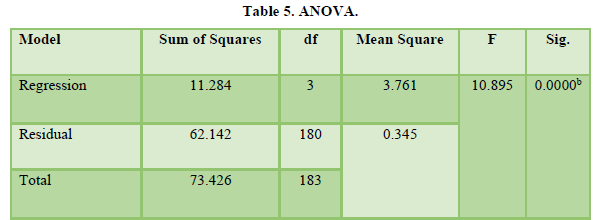

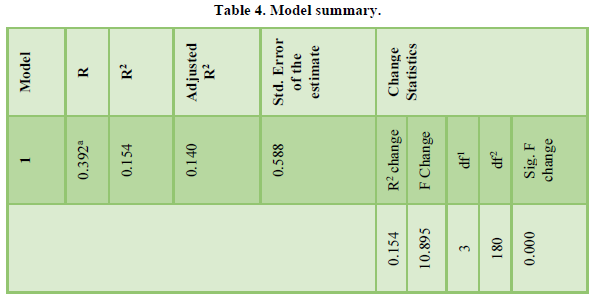

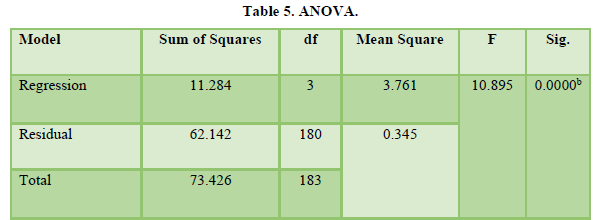

After checking the required assumptions, multiple regression analysis was performed to understand by how much each of the components of FWAs, i.e., Flextime Schedule, Compressed Workweek and Telecommuting explain the dependent variable, i.e., Job Satisfaction. The Model Summary, ANOVA, results of regression for each independent variable (components of FWAs) with the job satisfaction of the employees and summary result are presented below (Tables 4-6).

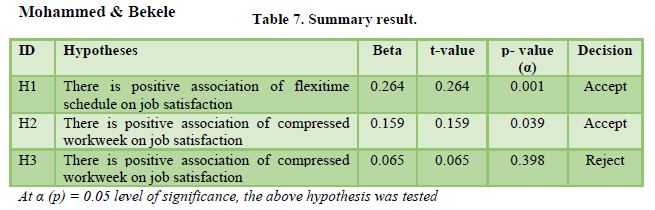

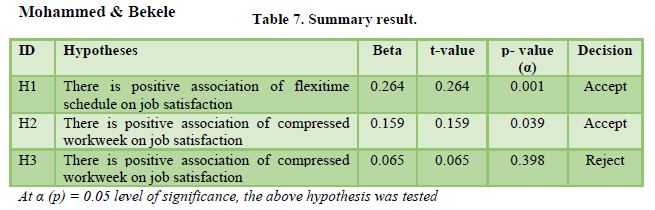

According to the multiple regression analysis above, the study specifically aimed at proving the research hypothesis, i.e., as shown on Table 7. From the regression analysis and the summary result, it can be seen that R-square value of 0.15 that signifies 16% of the variation in job satisfaction can be explained by the combination of the three components of FWAs. This means that the unit change in these three forms of FWAs will result to a change in job satisfaction by a factor of 0.15 at 5% significant level. According to Cohen (1988), R2 values are assessed 0.26 substantial, 0.13 moderate, and 0.02 week (Cohen, 1988). In this case, the effect the independent variables on the dependent variable with R-square value of 0.15 is more than moderate level.

As pointed out by several empirical studies, flextime schedule as independent variable has showed the largest value of Beta, i.e. β=0.264, p=0.001, in comparison to the two independent variable, i.e. Compressed Workweek (β=0.159, p=0.039) and Telecommuting (β=0.065, p=0.398). This affirms the claim that Flextime Schedule is the most commonly used FWAs used across organizations as well as its strong effect in enhancing job satisfaction (Ronda, Ollo-López & Ollo-López, 2016; Omondi, & K’Obonyo, 2018; Rahman, 2019; Jackson & Fransman, 2018; SHRM, 2020; SHRM, 2016).

However, one factor of FWAs, i.e., Telecommuting (β=0.065, p=0.398) could not be accepted, as the level of acceptance of p is not less than

As already pointed out under the literature review section, the positive effect of workplace flexibility is dependent on a number of factors including country context in identifying the appropriate FWAs modality (Albion, 2004, SHRM, 2015). In view of these empirical studies, FWAs cannot be implemented uniformly across all cultures. There are a number of factors including country context that need to be considered in designing workplace flexibility. It is also important to note that in line with prior studies, the effect of compressed workweek on job satisfaction is lower than the effect of flextime schedule on job satisfaction (Rahman, 2019; Rwashdeh, Almasarweh & Jaber, 2016).

CONCLUSION

The objective of this study was to explore the positive effects of flextime schedule, compressed workweek and telecommuting on job satisfaction. The analysis showed that there is significant positive effect of flextime schedule (R = 0.39, R2 = 0.264, p = 0.001) and compressed workweek (R = 0.39, R2 = 0.159, p = 0.398). This means that increase in the use of flexible working arrangements (flextime schedule and compressed workweek) can lead to increase in employee job satisfaction of the ECA in Addis Ababa. The independent variables reported R value of 0.39 and R2 = 0.15 which means that 15% of corresponding variations in employee job satisfaction can be explained by flexible working arrangements.

It is evident from this study and prior similar empirical studies that adoption of flextime schedule and compressed workweek FWAs as a human resources management practice contribute in terms of enhancing employee job satisfaction. Nevertheless, all forms of FWAs cannot be uniformly applied across cultures and different contexts, as its effectiveness is highly dependent on several factors. A case in point from this study was, absence of significant relationship between telecommuting and job satisfaction from the perspective of Ethiopian national employees of ECA in Addis Ababa. Contrary to prior studies, this study disproves that there is no significant relationship between telecommuting (β=0.065, p=0.398) and job satisfaction from the perspective of Ethiopian national employees of the ECA.

Even though the adoption and implementation of FWAs as an innovative human resources management practice at the ECA is at nascent stage, flexible schedule and compressed workweek contribute in enhancing the job satisfaction of the Ethiopian national employees of the ECA. It is therefore believed that the outcome of this study can serve as an input in exploring further on identifying context relevant FWAs as one key provision towards maximizing employee job satisfaction. This study also showed that telecommuting has no significant relationship on job satisfaction. Therefore, further study could be considered in this area from Ethiopian context, as the outcome of prior studies focus on the experiences of organizations from the developed world.

There are limitations of the study, which could be considered if further research is conducted. Due to the prevailing challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been difficult to obtain a greater number of respondents and be able to get more accurate data from the diverse UN offices located within the ECA compound in Addis Ababa. In order to boost the accuracy of research findings in the area of FWAs, future research should consider increasing the sample size as well as maximize the diversity of respondents from different organizations or sectors. The study only focuses on employees of the ECA and it is believed that a comparative analysis could be performed in diversified industries such as private and government sectors in Ethiopia. Moreover, there is research gap in FWAs in Ethiopia, therefore as an innovative human resource management practice in obtaining and sustaining the human capital, the factors of FWAs need to be studied further.

- Ashley, C., Roe, D. & Goodwin, H. (2001). Pro-Poor Tourism Strategies: Making tourism work for the poor. Available online at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3246.pdf

- Ababa, A. (2020). Ethiopia Orders Federal Employees to Work from Home to Mitigate Spread of COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.fanabc.com/english/ethiopia-orders-federal-employees-to-work-from-home-to-mitigate-spread-of-covid-19/

- Ababa, A. (2019). Labour Proclamation in Ethiopia No. 1156-2019.Available online at: file:///C:/Users/user1/Downloads/Labour-Proclamation-No.-1156-2011.pdf

- Addis, S., Dvivedi, A. & Beshah, B. (2018). Determinants of job satisfaction in Ethiopia: Evidence from the leather industry. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 9(4), 410-429.

- Albion, M. J. (2004). A measure of attitudes towards flexible work options. Australian Journal of Management 29(2), 275-294.

- Allen, T.D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior 58(3), 414-435.

- Allen, T.D., Golden, T.D. & Shockley, K.M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science 16(2), 40-68.

- Ansong, E. & Boateng, R. (2017). Organizational adoption of telecommuting: Evidence from a developing country. Wiley 1-15.

- Armstrong, M. & Taylor, S. (2014). Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/user1/Downloads/Armstrongs%20Handbook%20of%20Human%20Resource%20Management%20Practice_1.pdf

- Baltes, B. & Sirabian, M. (2017). Compressed workweek. The sage encyclopedia of industrial and organizational psychology. Sage Publications, pp: 202-203.

- Baltes, B., Briggs, T.E., Huff, J.W., Wright, J.A. & Neuman, G.A. (1999). Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology 84(4), 496-513.

- Bird, R.C. (2010). Four-day work week: old lessons, new questions symposium: redefining work: Implications of the four-day work week - the four-day work week: views from the ground. Connecticut Law Review 42(4), 1059-1080.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Available online at: http://www.utstat.toronto.edu/~brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

- Cox, W. (2009). Executive Summary: Improving Quality of Life through Telecommuting. Available online at: https://itif.org/files/Telecommuting.pdf

- Cranet Survey on Human Resources Management. (2005). Available online at: http://www.ef.uns.ac.rs/cranet/download/internationalreport2005-1.pdf

- Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and mixed methods approach. 5thedition- Sage publications pp: 304.

- Dettmers, J., Kaiser, S. & Fietze, S. (2013). Theory and practice of flexible work: Organizational and individual perspectives. Introduction to the special issue. Management Revue 24(3), 155-161.

- Dissanayake, K. (2017). Teleworking as a mode of working for women in Sri Lanka: Concept, challenges and prospects. IDE Discussion Paper No. 680, 1-27.

- Facer, R.L. & Wadsworth, L. (2008). Alternative work schedules and work-family balance: A research note. Review of Public Personnel Administration 28(2), 166-177.

- Huws, U., Jagger, N. & O’Regan S. (1999). Teleworking and Globalization. Available online at: https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/358.pdf

- HR Portal. (2019). Flexible Working Arrangements. Available online at:https://hr.un.org/page/flexible-working-arrangements/options-and-eligibility.

- Ivancevich, J., Olekalns, M. & Matterson, M. (1997). Organizational Behavior and Management. 1st Australasian edition, pp: 725.

- Jackson, L.T.B. & Fransman, E.I. (2018). Flexi work, financial well-being, work life balance and their effects on subjective experiences of productivity and job satisfaction of females in an institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 21(11).

- Kim, S.S., Galinsky, E. & Pal, I. (2020). One Kind Word: Flexibility in the Time of COVID-19. Available online at: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/ow8usu72/production/e09f06cb1ed14ae25da4753f60a942668f9dc269.pdf

- Lakshmi, V., Nigam, R. & Mishra, S. (2017). Telecommuting–A Key Driver to Work-Life Balance and Productivity. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 19(1), 20-23.

- Maxwell, G., Rankine, L., Bell, S. & MacVicar, A. (2007). The Incidence and Impact of FWAs in Smaller Businesses. Employee Relations 29(2), 138-161.

- McGuire, J.F., Kenney, K. & Brashler, P. (2010). Flexible Work Arrangements: The Fact Sheet. Available online at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/legal.

- McNall, L.A., Masuda, A. & Nicklin, J.M. (2009). Flexible Work Arrangements, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Work-to-Family Enrichment. The Journal of Psychology 144(1), 61-81.

- Miller, T. (2016). How Telecommuters Balance Work and their Personal Lives. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/user1/Downloads/TinaMillerDissertation.pdf

- Mungania, A.K., Waiganjo, E.W. & Kihoro, J.M. (2016). Influence of Flexible Work Arrangement on Organizational Performance in the Banking Industry in Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences 6(7), 159-172.

- Nicholas, B. & Thomas, A. (2010). Teleworking in South Africa: Employee benefits and challenges. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 8(1), 1-10.

- Nijiru, P., Kiambati, K. & Kamau, A. (2015). The influence of flexible work practices on employee performance in publicsector in the ministry of interior and coordination of national government. Scholars Bulletin 1(4), 102-106.

- Okoli, N.J. (2016). The slow adoption of telecommuting in South Africa. Available online at: http://etd.cput.ac.za/handle/20.500.11838/2424

- Omondi, A. & K’Obonyo. (2018). Flexible work schedules: A critical review of literature. The Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management 5(4), 2069-2086.

- Ogueyungbo, O.O., Maloma, A., Igbinoba, E., Salau, O., Maxwell, O, et al. (2019). A review of flexible work arrangements initiatives in the Nigerian Telecommunication Industry. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology 10(03), 934-950.

- Pallant & Julie. (2001). SPSS Survival Manual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Data Analysis using SPSS for Windows (Versions 10 and 11). Available online at: http://www.fao.org/tempref/AG/Reserved/PPLPF/ftpOUT/Gianluca/stats/SPSS.Survival.Manual.ISBN.0-335-20890-8.pdf

- Price, J.(1997). Handbook of Organizational Measurement. International Journal of Manpower 18(6), 303- 558.

- Pruchno, R., Litchfield, L. & Fried, M. (2020). Measuring the Impact of Workplace Flexibility. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/user1/Downloads/Measuring%20the%20Impact%20of%20Workplace%20Flexibility.pdf

- Rahman, M.F. (2019). Impact of Flexible Work Arrangements on Job Satisfaction among the Female Teachers in the Higher Education Sector. European Journal of Business &Management 11(18), 97-107.

- Rau, B., & Hyland, M. (2002). Role conflict and flexible work arrangements: The effect on applicant attraction. Personnel Psychology 55(1), 111-136.

- Rawashdeh, A.M., Almasarweh, M.S. & Jaber, J. (2016). Do flexible work arrangements affect job satisfaction and work-life balance in Jordanian private airlines? International Journal of Information, Business & Management 8(3), 173-185.

- Ronda, L., López, A.O. & Legaz, S.G. (2016). Family-friendly practices, high-performance work practices and work–family balance: How do job satisfaction and working hours affect this relationship? Management Research: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management 14(1), 2-23.

- SHRM, (2015). SHRM Research: Flexible Work Arrangements. Available online at: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/special-reports-and-expert-views/Documents/Flexible%20Work%20Arrangements.pdf

- Siddhartha, V., & Malika, C. (2016). Telecommuting and Its Effects in Urban Planning. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology 5(10), 448-453.

- Sitotaw, S.S. (2019). Assessing socio-economic impact of road traffic congestion in Addis Ababa city in case of Megenagna to CMC Michael road segment. Available online at: http://etd.aau.edu.et/bitstream/handle/123456789/18412/Sileshi%20Setito.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Spector, P.E. (1997). Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes and Consequences, Sage Books. Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452231549

- SHRM. (2020). Managing Flexible Work Arrangements. Available online at:https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and samples/toolkits/pages/managingflexibleworkarrangements.aspx

- Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. (2011). Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2, 3-55.

- Teh, B.H., Soh, P.C.H., Loh, Y.L., Ong, T.S. & Hong, Y.H. (2017). Enhancing the Implementation of Telecommuting (Work from Home) in Malaysia. Asian Social Science 9(7), 1-11.

- United Nations. (2019). Information Circular from the Assistant Secretary-General for Human Resources on Flexible Working Arrangements. Available online at: https://undocs.org/en/ST/IC/2019/15

- United Nations. (2020). UN75: Shaping our future together. Available onlineat:https://ethiopia.un.org/en/87694-un75-shaping-our-future-together