4177

Views & Citations3177

Likes & Shares

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced travel and tourism worldwide, both domestic and abroad, to a fraction of the norms of which entire economies have become accustomed or even dependent. While our global and shared circumstances are economically distressing at best, those who hold optimistic or innovative viewpoints might question how this global health crisis presents opportunities not only towards the improvement of environmental and cultural health, but also towards transformations of which have not previously been considered or even imagined. The purpose of this paper is to continue a line of inquiry about the transformative nature and potential of the niche tourism segment called temple stays. This conceptual work builds upon a previous publication where a Korean American scholar shared in detail and deciphered her lived experience of a temple stay in Korea as transformative travel (Ross, et al, 2019). As a primer, this paper begins with an overview of the scant literature pertaining to temple stays followed by an overview of travel and tourism in Korea during the pandemic. The heart of this paper delivers a solution of templestaycations. Playing upon our collective need to limit ourselves to staycations, this idea combines the burgeoning tourism niche of temple stays with the growing need for meaningful, healing, and/or growth-producing experiences. By employing advanced technology and boldly enacting nimble change, governments, industry, and temple leaders have the opportunity to pivot, and open the temple doors to far more than hundreds of thousands. One potential is for individuals to learn from ancient cultures how to transform their lives, practices, and homes into sanctuaries of holistic and even spiritual wellbeing.

Keywords: Temple stay, Templestaycation, Transformative travel, Transformative tourism, Pandemic tourism, Virtual tourism, Temple stay.

INTRODUCTION

In concert with the government, the largest Buddhist order in Korea---the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism---strategically developed temple stays to address lack of housing for the 2002 FIFA World Cup soccer tournament between Korea and Japan. In 2004, the Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism (CCKB), a subset of the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, was established to design, manage, and promote multiple-day residential retreat programming. The Korean TempleStay programs are equipped to offer travelers a glimpse into the clothing, food, meditations, chants, music, arts, and teachings transpiring during daily life within 139 operational monasteries. This niche travel market uniquely combines cultural, religious, heritage and therapeutic travel. Since its launch, temple stays have become a means for Koreans and internationals to be immersed in Korean history, culture, and Buddhism and is considered a rite of passage for Korean’s who are transition as an example from graduating from college to attaining their first professional job as a basis for clarity and meaning. While temple stay’s originated in South Korea, there is a growing trend of temples across the world to incorporate temple stays into their offerings both as a source of revenue as well as to provide a space for individuals seeking clarity and transformation.

The purpose of this paper is to extend a descriptive paper (Ross, Hur, & Hoffman, 2019) that examined Korean American scholar Jungyun Christine Hur’s temple stay experience in a Korean monastery called Temple Hwaeomsa. In that paper, Hur gave a descriptive analysis of her temple stay juxtaposed ten activities of transformative travel (Ross, 2010). The exploration concluded that she did engage in transformative activities and found her temple stay to be transformational. This paper offers an abridgement of literature about temple stays, synopsis of tourism and the temple stay program in South Korea during pandemic conditions, and description of one yet-unrealized opportunity that the CCKB and monasteries worldwide might consider implementing now, and in the future.

LITERATURE

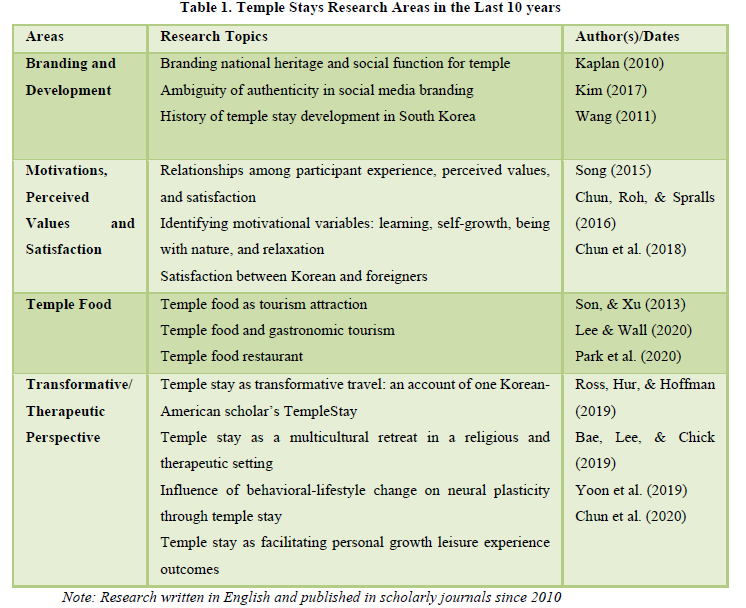

It is surprising to discover that nearly two decades after the inception of temple stays, academic analysis of this niche tourism segment has received relatively little scholarly attention. We categorize the literature into four topic areas that include (a) branding & development, (b) motivation, perceived value, and satisfaction, (c) temple food and, (d) transformative/therapeutic Table 1. Earlier publications focused on the history and development of temple stays (Kaplan, 2010; Wang, 2011). As temple stay travel has increased, scholars have investigated patrons’ motivations, perceived values, foreign and domestic satisfaction, and culinary experiences (Chun, Roh, & Spralls, 2016; Chun, Roh, Spralls, & Kim, 2018; Lee & Wall, 2020; Park, Bonn, & Cho, 2020; Son & Xu, 2013; Song, 2015).

There are myriads of ethical, cultural, appropriation and hegemonic dilemmas that come when a government and religious sects are involved in opening monastery doors to the public and marketing ancient communities of spiritual practice. Although a few papers discussed such issues (Bae, Lee, & Chick, 2019; Ross, Hur, & Hoffman, 2019), Kim’s (2017) investigation into authenticity of “neoliberal brand practices” in digital media that promote the temple stays vacillates between the sacred and secular. Recent discourse on temple stays explore personal growth and behavioral-lifestyle change through temple stays (Bae, Lee, & Chick, 2019; Chun, Roh, Spralls, & Cheng, 2020; Yoon, Bae, Kwak, Hwang, & Cho, 2019) and temple stays as transformative travel (Ross, Hur, & Hoffman, 2019). The research about the outcomes of temple stay have only started to explore and scrutinize the complexities, risks, and potential of this tourism niche.

THE PANDEMIC AND SOUTH KOREAN TOURISM

The travel and tourism industry has shifted significantly since the beginning of the pandemic that emerged in China and South Korea in late 2019 and the United States in February 2020. The United Nations World Travel Organization stated in a report in May 2020, “never before in history has international travel been restricted in such an extreme manner” (Lee, 2020). As a result, the World Tourism Organization is expecting tourism revenue will drop $300 to 500 billion dollars in 2020, which accounts for one-third of the $1,500 billion generated in 2019 (Shin, 2020). The Korean Tourism Association reported in March 2020, that the “number of foreign tourists visiting South Korea fell by 94.6% compared with the same period last year” (Salmon & Shin, 2020).

At the time of this article publication, John Hopkins University and Medicine reported that South Korea has had 25,775 cases, 23,834 recoveries, and 457 deaths associated with COVID-19 (2020). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a Level 3 Travel Health Notice for South Korea. South Korea currently has stringent travel regulations to increase the safety and health of those visiting as well as residents (Gong, 2020). Failure to comply could result in up to a year in prison or up to 10 million won (nearly $9,000) in fines (Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2020). Domestic travellers have been required to visit a family member and quarantine for 14 days with a tracking device as well as with a journal and medical equipment to take temperature issued by the government. If an international traveller is not visiting family, they are transferred to a government regulated facility upon arrival in country for a 14-day quarantine costing anywhere from $300-$1,000 per night to the traveller. Understanding the current regulations and repercussions for not complying, clearly depicts why the number of international tourists visiting South Korea is so low.

Even though South Korea recorded the highest number of positive cases outside of China at the outset of the pandemic outbreak (Lewis, 2020), the curve of confirmed cases rates flattened and on October 12, 2020, the government reduced the Threat Level to 1. Prior to the pandemic, there was a growing niche of individuals who travelled to Buddhist temples for the purpose of personal clarity, spirituality, and transformation.

Although the cases of the pathogen in South Korea are lower than 89 countries worldwide, the pandemic has severely affected outbound travel causing an increase in domestic travel (International Trade Administration, 2020), spending on house renovations, home-camping, and camping equipment (Roh & Yi, 2020). In October 2020, South Korea lifted its assembly ban on large groups, reopened buffet restaurants, nightclubs, karaoke’s, venues categorized as high risk, and expanded in-person attendance at schools while upgrading detailed disease prevention guidelines for each facility (Gong, 2020). While the South Korean government placed new rules and regulations on social gatherings and the use of public and private spaces, churches and temples began to reopen in communities. Between September 29 and October 4, 2020, more than 31 million South Koreans travelled for family reunions and vacations, but just 44 infections linked to holiday travel have been confirmed.

TEMPLE STAYS

In order to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the CCKB suspended the TempleStay program and all religious gatherings in early March, 2020. Following a decline in infection rates, the CCKB resumed temple stay programs for individuals in late April while programs for groups remained suspended (Lewis, 2020). The CCKB announced that from March to October, they would offer 4-day TempleStays at 10 locations, to medical staff and health officials “for healing and regaining peace of mind” (Jing, 2020). Such social contributions are expected to be continued as temples become more open to public and engaged in community and society.

TEMPLE STAYCATION OPPORTUNITIES FOR SOUTH KOREA AND BEYOND

Although South Korea has resumed most transportation options, including airport operations and re-opening of borders and business operations, day cares, and schools, Oxford Economics reports that international travel is not expected to rebound to 2019 levels until 2024 (Clausing, 2020). Because it is in the best or only interest of travelers to vacation near or literally at home, it is time that tourism heed the shift. It has been required of most schools and business’s to go virtual therefore we suggest that tourism must go virtual. Now is the “opportunity for tourism innovation;” that transforms tourism into a more socially just, responsible, and sustainable industry (Gombault, 2020). Businesses and governments at the forefront will create specialized experiences in the form of staycations, e-tourism, slow tourism, digital heritage, and live online broadcasting (Gombault, 2020). In order to offset massively truncated tourism revenues, the caretakers and creators of temple stays must begin to imagine how to bring temple stay immersion retreat experiences to seekers, at home or in a virtual manner.

HOW MIGHT A TEMPLESTAYCATION WORK

Given a scenario that fits within the average person/family’s budget and time constraints, just how many people would seize an opportunity to “stay” for 4-5 days in an operational, ancient Buddhist Temple? Given that 63% of people aged 18-34 watch live streaming content regularly, leaves wide-open, the potential for tourism to use this and similar technologies (Patel,2018). with a relatively modest investment in technology, the CCKB and the South Korean government or other temple’s around the world could pioneer a timely and far-reaching tourism trend: TempleStaycations.

Specifically, of the 39 temples identified by the CCKB as having the highest quality operations (CCKB, 2020), the CCKB could select 3-5 temples to showcase a new paradigm of travel and tourism. First steps towards implementation might involve attaining the blessing and agreement of temple leaders, monks, and staff. Then, collaboratively with temple leaders, revise TempleStay programs to match the limitations/potential of virtual/remote experiences, install video/technological equipment, produce educational/programming materials, and promote the novel opportunity to target markets.

In the comfort of their home, the TempleStaycation pilgrim can log into a live stream at scheduled times and watch, listen, and absorb the sounds of the music, colors and textures of the art, movements of dance, effects of prayer, sound reverberations of chanting, and ethereal meditations as they transpire in and around the temple. Live camera feeds could enable patrons to view the sounds and sights of the natural surroundings and temple architecture or to meditate in a garden temple fountain or alongside a nearby babbling brook. Because technology allows the opportunity to be more than a passive recipient, the visitor can even enjoy remotely, a one-to-one visit with a monk. The CCKB could aim to bring the temple to the pilgrim in tangible ways by sending a package of art supplies and a simple musical instrument encouraging virtual interactions. During relevant sessions, the traveler can learn experientially about Buddhist history, culture, and spirituality while comingling with the monks. The package might include educational materials that portray the historical and cultural aspects of the TempleStaycation.

TEMPLESTAYCATION AS TRANSFORMATIVE TRAVEL

A TempleStaycation can deliver more than a visual and auditory wonderland that includes experiential engagement. Using experience design as one guide (Pine & Gilmore, 1999), the CCKB and other operational monasteries can design TempleStaycations as transformative travel. Creating a space and place for individuals to connect at a deeper level with themselves and their surroundings through this virtual experience.

This ultimate travel type requires considerable frontend planning and preparation so that pilgrims can become co-curators of their own experience. Travelers in this niche seek to be affected deeply or touched spiritually and are highly motivated to make sacrifices to produce personal growth and change (Pine & Gilmore, 1999). They probably possess the resources, occupation, self-discipline, and living arrangements to support 5-days of sequestered introspective immersion, at home virtually.

As transformative travel, the TempleStaycation invites, equips, and teaches the pilgrim how to transform one’s home into a “temple” and prepare one’s body and psyche to become quieted, opened, receptive, and informed. But how might this look and work? The TempleStays in South Korea offer thematically designed packages. The CCKB could build upon existing programming by creating educational and preparatory materials that help pilgrim(s) to prepare for and maximize the therapeutic, restorative, and spiritual benefits of a TempleStaycation. Ideally, the preparatory materials derive from Buddhist teachings and practices. For example, the pilgrim could learn how the monks ritually organize, clean, and create sacred space so that the seeker can “transform” their home into a sacred space. The TempleStaycationers might purchase a certain type of bell or learn how to clear or situate furniture or place candles creating a therapeutic environment. The individual might be readied by completing a 24 or 48-hour fast, receiving a therapeutic massage, reciting ancient prayers or teachings, or writing personal goals. The CCKB could create a temple food menu, including a grocery list with directions, so that the initiate can purchase, prepare, and eat temple food “alongside” the monks. To ensure uninterrupted solitude and the feeling of retreat, pilgrims might commit to abstaining from mobile phones, computer/emails/social media, televisions, entertainment, etc. or even communications with friends, family, and colleagues.

CONCLUSION

The spiritual, contemplative, therapeutic, and uplifting qualities of temple stays are arguably needed by more people than ever before. The ongoing pandemic conditions that are causing people around the world to be vacation deprived and for the collective to seek escape from pandemic routines that transports them into novelty are no doubt mounting. Witnessing profound loss of human life, enduring the threat of sickness or even death by an invisible pathogen adds existential angst and stressors at a global and local level.

Using technology, the modern traveler could “be” within temple walls, surrounded by nature, and in the presence of monks who embody an ancient spiritual tradition. In such “spaces”, TempleStaycationers could make use of a monastic retreat to question reality, savor rest that comes from inner peace, discover new possibilities, and explore one’s self. From a host perspective, TempleStaycations offer monks---who traditionally serve the world through a private life---the opportunity to become active purveyors of transformation within and among countless people worldwide. Not only would seizing the opportunity create an opportunity for introspective transformation of an individual during this global pandemic but also their given space where they are “sheltering in place”, create a meaningful use of time while engaging in a TempleStaycation.

- Bae, S., Lee, C., Chick, G. (2019). A multicultural retreat in exotic serenity interpreting temple stay experience using the Mandala of Health model. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 24(8), 789-804.

- Chun, B., Roh, E.Y., Spralls, S.A., & Cheng, C. (2020). Personal growth leisure experience in Templestay International tourist outcomes satisfaction and recommendation. Journal of Leisure Research.

- Chun, B., Roh, E.Y. & Spralls, S.A. (2016). Living Like a Monk Motivations and experiences of international participants in templestay. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimag 5, 20-38.

- Chun, B., Roh, E.Y., Spralls, S. A., Kim, Y. (2018). Predictors of templestay satisfaction a comparison between korean and international participants. Leisure Sciences 40(5), 423-441.

- Clausing, J. (2020). Oxford Economics predicts rapid economic recovery post Covid19. https://www.travelweekly.com/Travel-News/Travel-Agent-Issues/Oxford-Economics-predicts-rapid-economic-recovery-post-coronavirus.

- Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism (2020). The Introduction and History of Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism. Available online at: http://www.kbuddhism.com

- Gombault, A. (2020). Coronavirus and other problems a dark year for global tourism. Available online at: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/opinion/4098500.html

- Gong, S. (2020). South Korea Eases Coronavirus Restrictions Touts 'Exceptional Success. Available online at:

- https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/10/19/925341006/south-korea-eases-coronavirus-restrictions-touts-exceptional-success

- International Trade Organization (2020). South Korea Commercial Guide Travel and Tourism. https://www.trade.gov/knowledge-product korea-travel-and-tourism/

- Jing, L. (2020). Free temple stay for medical staff and health officials. The Korea Bizwire. Available online at:

- http://koreabizwire.com/free-temple-stay-for-medical-staff-and-health-officials/155730

- John Hopkins (2020).University & Medicine CoronaVirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering CSSE at Johns Hopkins. Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html URL

- Kaplan, U. (2010). Images of Monasticism The Temple Stay Program and the Re-branding of Korean Buddhist Temples. Korean Studies 34, 127-146.

- Kim, S.S. (2017). Authenticity Brand Culture and Templestay in the Digital Er The Ambivalence and In Betweenness of Korean Buddhism. Journal of Korean Religions 8(2):117-146.

- Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency (2020). https://www.cdc.go.kr/cdc_eng/

- Lee, A.H.J. & Wall, G. (2020). Temple Food As a Sustainable Tourism Attraction Ecogastronomic Buddhist Heritage and Regional Development in South Korea. Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism 4(4), 209-222.

- Lee, Y.N. (2020). 5 charts show which travel sectors were worst hit by the coronavirus. CNBCWorld Economy. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/06/coronavirus-pandemics-impact-on-travel-tourism-in-5-charts.html

- Lewis, C. (2020). Buddhist Temple Stays Suspended in Korea as Coronavirus Spreads Religious Gatherings Under Scrutiny Buddhistdoor Global.

- Park, J., Bonn, M.A., Cho, M. (2020). Sustainable and Religion Food Consumer Segmentation Focusing on Korean Temple Food Restaurants. Sustainability 12, 3035.

- Patel, N. (2018). Why you should care about live streaming. Available online at: https://neilpatel.com/blog/live-streaming-importance-2018/

- Pine, J., & Gilmore, J. (1999). The Experience Economy, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Roh, J. & Yi, H.Y (2020). As travel restrictions make foreign holidays harder South Koreans are undertaking elaborate home renovations instead. Thomson Reuters Foundation News. Available online at: https://news.trust.org/item/20200825034051-160bf

- Ross, S. L. (2010). Transformative Travel an Enjoyable Way to Foster Radical Change, ReVision 31(3/4), 54-61.

- Ross, S., Hur, J., Hoffman, J. (2019). Temple Stay as Transformative Travel An Experience of the Buddhist Temple Stay Program in Korea. Journal of Tourism Insights 9(1).

- Salmon, A., & Shin, M. (2020). Globtrotting Korean tourists to holiday at home. Asia Times. Available online at: https://asiatimes.com/2020/07/globetrotting-korean-tourists-to-holiday-at-home/

- Shin, S. (2020). How South Korea has eliminated Corona Virus risk from foreign travelers. Available online at:

- https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/how-south-korea-has-eliminated-coronavirus-risk-foreign-travelers-n1240957

- Son, A., & Xu, H. (2013) Religious food as a tourism attraction the roles of Buddhist temple food in Western tourist experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism 8(2-3), 248-258.

- Song, H. J., Lee, C., Park, J.A., Hwang, Y.H., & Reisinger, Y. (2015). The Influence of Tourist Experience on Perceived Value and Satisfaction with Temple StaysThe Experience Economy Theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 32 (4), 401-415.

- Wang, W. (2011). Explore the Phenomenon of Buddhist Temple Stay in South Korea for Tourists. Master thesis, UNLV.

- Yoon, Y.B., Bae, D., Kwak, S., Hwang, W.J., Cho, K.I., etal. (2019). Plastic Changes in the White Matter Induced by Templestay a 4-Day Intensive Mindfulness Meditation Program. Mindfulness 10, 2294-2301.