Research Article

A RESEARCH OF BRAND EXTENSION INCHAIN RESTAURANTS:APPLICATION OF BRAND TRUST, FAMILIARITY AND ATTITUDE OF PARENTBRAND AND EXTENDED BRAND

2923

Views & Citations1923

Likes & Shares

This research employed a framework incorporating brand image, perceived quality, brand awareness, brand trust and brand familiarity to examine whether brand attitude of extended brand and brand attitude of family brands were affected. By using questionnaire survey, the customers of chain restaurants were taken as the objects. A total of 469 usable responses were obtained. To test the hypotheses, a bootstrapping analysis for moderated mediation, the PROCESS macro in SPSS for Model 4 and Model 9 was employed in this research. This study identified the conceptual framework and provided an understanding of brand extension in chain restaurants. Finally, limitations of this study and several directions for future research were proposed.

Keywords: Parent brand, Brand extension, Brand trust, Brand familiarity, Brand attitude, Chain restaurant

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, global brands are trying to increase sales revenue through brand extension promotion (Pina, Iversen, & Martinez, 2010). It’s expected to make the consumers connect the products of parent brand with those of extended brand, and get the consumers easily recognize and accept extended brand. What are the main advantages for the enterprise to implement brand extension? Extending the market of parent brand, reducing the cost of launching extended brand and lowering the risk of extended products are the advantages for the enterprise to employ the strategy of brand extension (Tauber, 1988; Ting & Lo, 2006). It’s the reason why the enterprise tries to develop its firm in brand extension. In hospitality industry, brand extension is a strategy implemented by chain hotels and chain restaurants; for example, the Hyatt hotel group developed the brands such as Park Hyatt, Grand Hyatt, Hyatt Regency, Andaz and Hyatt Place by brand extension. In this way, the enterprise could enter a new market segment and access consumers of different market segments to promote the firm’s growth. In Taiwan, brand extension is a strategy for chain restaurants to develop their business; for example, the Wowprime Corporation utilized brand extension to develop Wang Steak, Tasty Steak, Chamonix restaurant, ikki Japanese Cuisine and other brands. In hotel industry, the Regent Hotels Group developed Silks Place and Just Sleep. Obviously, brand extension is a strategy which facilitates the enterprise extend the market to different segments efficiently.

These are important strategies for an enterprise’s growth; however, could brand extension have any negative influence on the firm? It was addressed that inappropriate brand extension could damage the reputation and entire image of parent brand (Aaker, 1990; Doyle, 1990; Morrin, 1999). And, it could dilute the image of family brands (Chang, 2002). Thus, it could result in vanishing the advantages of brand extension; such as obtaining brand awareness promptly, getting familiar with the brand and reaching high sales revenue. Moreover, it could damage the sales revenue of parent brand (Ries & Trout, 1986). In order to avoid these negative impacts of brand extension, Kwun (2010) proposed that monitoring the dilution or promotion of a brand name is a manager’s important job. It’s crucial to avoid negative perception and lift brand-related equity. In order to manage family brands efficiently, the manager need to understand how the consumers perceive brand extension and its impact on family brands. Owing to the insufficient relevant research of brand extension for hospitality industry, it’s an intention of this research to deeply explore the relationships of parent brand, extended brand and family brands in hospitality industry.

In the past decade, the issues of food safety were seriously concerned by the public and the government in Taiwan. In 2011, an illegal plasticizer has been found in a number of beverages from well-known manufacturers. In 2013, the starch-processed food was made in toxic starch or tainted starch which contained maleic acid/maleic anhydride. In 2014, the gutter oil manufacturer collected leftover from restaurants, waste from sewers, and waste animal fat to produce gutter oil. These food safety events spread to the suppliers and restaurants which included well-known chain restaurants. Like Wowprime Corporation, the Wang Steak and its extended brand were affected by using gutter oil. Thus, consumers’ brand trust on its parent brand and extended brand has declined. Except for the issues brought out by the suppliers, the restaurateurs didn’t honestly claim the ingredients or cooking method of the meals. The issues of food safety could make consumers doubt the brand and have negative impact on brand trust; furthermore, it could drop off consumers’ purchasing intention and decrease the sales revenue. Form these food safety events, it revealed the importance of consumers’ brand trust on a brand development. Especially for the relationship of brand extension, brand trust not only influenced one product or one brand itself, but also influenced its extended brand or its parent brand, even the brand family.

Brand trust, it was seen as a component of the force which held the consumers and brand together (Hiscock, 2001). Previous study addressed that under the situation of risks, brand trust was the confidence and expectation that the consumers could believe in (Delgado-Ballester, Munuera-Aleman, & Yagüe-Guillén, 2003). Regarding the advantages of brand extension, based on what the consumers rely on the parent brand, the acceptance for the products could increase. However, if the consumers’ brand trust on parent brand was changed, how did it affect consumers’ attitude toward extended brand or family brands? The difference of brand trust in customers’ mind could affect the effect of brand extension. Thus, in this research, it tried to utilize brand trust as a moderating variable in brand extension to explore the role of brand trust. It’s also one intention of this research.

Hardesty, Carlson and Bearden (2002) proposed that the consumers who had higher brand familiarity could understand the product and service of the enterprise and have better brand evaluation. The moderating role of brand familiarity was proved (Huang, 2016). Namely, the difference of brand familiarity in customers’ mind could affect the effect of brand extension. Therefore, brand familiarity was applied as a moderating variable in this research to examine its impact on the relationships among parent brand, extended brand and family brands.

Kwun (2010) pointed out that consumers’ evaluation for hotel extended brand and family brands was important. In order to reach the maximum profit, the managers need to understand the effect of consumers’ perception on extended brand and family brands. Regarding the evaluation of brands, brand image (Chiang & Jang, 2006; Kim & Kim, 2005; Tsai, 2005), brand awareness and perceived quality were the main components (Kim & Kim, 2004; Kim & Kim, 2005). Additionally, according to the above, brand trust and brand familiarity will be employed as moderating variables in this research. The role of brand trust and brand familiarity will be explored in different research frameworks, and the formed research models will be examined. The relationships of parent brand, extended brand and family brands could be expected to be deeply analyzed.

In this research, based on the theory of brand extension, brand image, brand awareness, perceived quality, brand trust and brand familiarity were applied to explore the relationships among parent brand, extended brand and family brands. It’ll facilitate the enterprise understand the impact of brand trust and brand familiarity on the success of brand extension more clearly. It could be helpful to the theoretical development of brand extension by clarifying the role of brand trust and brand familiarity. The objectives of this research are as follows:

- To explore the impact of brand image, brand awareness and perceived quality of parent brand on brand attitude of extended brand and family brands in chain

- To explore the moderating effect of brand trust and brand familiarity on the relationship of parent brand and extended brand, family brands in chain restaurants.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Brand extension Definition of brand extension

Brand extension is to continue using an existed brand in a new category of products (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Styles & Ambler, 1995; Tauber, 1981). It aims to lower marketing cost and increase consumers’ acceptance rate to enter a brand- new category of products by utilizing a successful brand name and establish brand equity (Aaker & Keller, 1990).

Brand extension could be separated into line extension and category extension (Farquhar, Herr, & Fazio, 1990). Line extension is to launch a new product by using the existed brand (namely the “parent brand”) into a new market segment, whereas this product is belonged to the original product category. Category extension is to launch a new product into a different product category by using the existed brand; thus, the parent brand and extended brand formed brand family. Tauber (1981) proposed that brand extension strategy is a way to seek growth in a new product market by using an old brand name. Brand attachment of parent brand may further influence consumers’ brand extension evaluation (Li & Wang, 2018). Based on the price, it could be classified to up extension (to launch a higher-price product) and down extension (to launch a lower-price product). Based on the direction of extension, the horizontal extension means applying an existed brand name in a new product category, and the vertical extension means launching a new product with different price or quality in the same category (Keller & Aaker, 1992).

In most of the hospitality industries, line extension was applied in employing the strategy of brand extension. The enterprise launched a new product by using the existed brand into a new market segment, whereas the product is belonged to hospitality industry.

The advantages and disadvantages of brand extension

Regarding the advantages which brand extension could bring out for the enterprise, Tauber (1988) addressed that there are four advantages- making use of the asset of original brand well, extending the sales of original brand, reducing the marketing cost and lowering the risk of extended products. Ting and Lo (2006) pointed out that the advantages of brand extension are transferring the original brand equity to extended products successfully, expanding the sales of original brand, increasing the popularity of original brand, lowering the marketing cost and risk, more positive advertising efficiency, and reducing consumers’ perception on risk. These are the reasons why the enterprise would try to develop brand extension.

Regarding the disadvantages of brand extension, it was also proposed by previous research. Ries and Trout (1986) proposed that the advantage of brand extension was only with short period. Even though through the power of original brand, it could obtain the awareness, familiarity and good sales revenue, these advantages could slash rapidly. Moreover, the success of extended product probably sacrificed the sales of original brand. And, if not using the brand extension well, it could affect the original brand. Especially while the extended products were launched on the market, it could disperse the original brand image, weaken brand association, and result in indefinite brand positioning in consumers’ mind (Morrin, 1999). Aaker (1990) proposed that the main risks of brand extension were lessening existed association, increasing new association and unfavorable association; furthermore, to damage the original brand equity. Besides, the unsuitable brand extension could confuse brand identity, debase the reputation of successful brand, and weaken entire brand image (Doyle, 1990).

Brand dilution, it means that consumers had negative belief on a specific brand while there’s weak relationship or inconsistent with the original brand image (Loken & Roedder, 1993). The image of family brands could be diluted by unsuitable brand extension. Although brand extension could create more market share and profit for the enterprise, the negative influence of brand dilution on parent brand and family brands shouldn’t be ignored (Chang, 2002).

To sum up the above, in order to develop the advantages and reduce the disadvantages, how the brand extension affected consumers’ perception and attitude is worth of being deeply explored in this research.

The factors influencing brand extension

Regarding the factors influencing the awareness and attitude of extended brand, it was found that the customers preferred extended brand while they preferred parent brand (Bhat & Reddy, 1997). When the enterprise was with better image or the products were more compatible, the effect of endorsement would be more significant (Bei & Cheng, 2004). And, the identification with the brand could positively influence consumers’ evaluation on parent brand and extended brand (Ho, Su, & Chang, 2004). It was found that perceived quality and brand image could affect brand image of family brands and repurchasing intention (Lin, 2006). It revealed that brand extension and parent brand awareness could affect consumers’ perceived value on extended brand (Lee & Jhu, 2013). Iyer, Banerjee, and Garber (2011) proposed that consumers’ attitude toward parent brand was the strongest factor influencing extended brand. Milberg, Goodstein, Sinn, Cuneo, and Epstein (2013) addressed that the quality of parent brand and the compatibility of extended brand with parent brand were crucial factors. To summarize the above, consumer’s brand image, brand awareness, perceived quality were the main factors influencing the evaluation of extended brand.

With the products of extended brand being launched in the market, the brand image of parent brand would be renovated and changed (Tauber, 1988). And, extended brand could cause the consumers re-evaluate the parent brand (Iyer et al., 2011). It didn’t easily recall the memory of extended brand when the consumers watched the advertisement of parent brand; on the contrary, it easily recalled the memory of parent brand when the consumers watched the advertisement of extended brand. It was mainly connected with family brands (or umbrella brand) in consumers’ mind (Farquhar et al., 1990; Morrin, 1999). The family brands (or umbrella brand) played a role of brand schema, and all of the product characteristics and brand knowledge were related with it (Sujan & Bettman, 1989). For the hotel industry, Kwun (2010) evaluated the impact of extended brand on family brands and revealed that perceived quality, brand ranking and brand awareness were crucial to consumers’ brand attitude. Therefore, consumers’ perception on parent brand could not only influence the evaluation of extended brand, but also influenced the evaluation of family brands, and parent brand.

Mollahosseini, Kermani, and Abassi (2011) pointed out that consumers’ information and knowledge for the brand could have impact on consumers’ brand attitude. Brand familiarity is an important variable for the formation of consumers’ attitude. In the process of extended brand attitude transferring to family brands, the moderating effect of brand familiarity was proved (Kwun, 2010). Previous research showed that there’s difference between the consumers with high brand familiarity and the consumers with low brand familiarity (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Boo & Mattila, 2002; Broniarczyk & Alba, 1994; Fazio, 1986). Thus, consumers’ brand familiarity with parent brand could affect the evaluation of extended brand.

Except for brand familiarity, brand trust was seen as consumers’ belief which could satisfy consumers’ needs and their behavior for preferred brand (Andaleeb, 1992; Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Aleman, 2001). Brand trust is an important indicator of brand strength (Burmann, Jost-Benz, & Riley, 2009). Tseng and Wang (2006) proved that brand trust could affect consumers’ trust for extended brand and purchasing behavior. According to the above, brand familiarity and brand trust played important roles for the influence of parent brand on extended brand.

Previous research had explored the influence of parent brand on extended brand, family brands, and its influence on consumers’ brand attitude (Iyer et al., 2011; Mollahosseini et al., 2011; Tseng & Wang, 2006). In this research, it focused on exploring consumers’ attitude toward extended brand and family brands, and the advantages and disadvantages of brand extension.

BRAND ATTITUDE

Attitude played an important role for explaining consumers’ behavior (Kwun, 2010). Consumers’ brand attitude was formed through brand characteristics; namely, brand attitude was formed in the process of consumers’ evaluation (Assael, 1998). Brand attitude was defined as an integral evaluation for a specific brand, including positive and negative attitude (Engel, Blackwell, & Miniard, 1993). Brand attitude is the level which it could make the consumers satisfied (Howard, 1994). Boo and Mattila (2002) addressed that consumers’ attitude included previous attitude and familiarity. These factors could affect consumers’ perception on brand relations and their evaluation on psychology and behavior related with the brand. As it can be seen, consumers’ brand attitude is usually one of the important factors influencing their purchasing decision.

For brand extension, it’s expected to affect consumers’ attitude toward extended brand through their attitude toward parent brand. Consumers’ extended brand attitude means that the attitude toward extended brand; namely, it’s consumers’ positive or negative evaluation on the extended brand while facing the brand extended from a parent brand (Kwun, 2010; Kwun & Oh, 2007). Parent brand attitude was found to significantly affect brand extension attitude (Chang & Chan-Olmsted, 2010). The attitude toward the parent brand has a positive influence on brand attitude toward extended brand, and then affects purchase intention toward extended brand (Chiang, Huang, & Huang, 2017). While implementing the strategy of brand extension, it’s expected to influence consumers’ attitude toward other products through their preference on a specific brand (Kwun, 2010). However, some research pointed out its negative influence on consumers’ attitude. Tsai, Lu and Lin (2010) employed quality, reliability, professionalism, cognitive performance to measure brand dilution through brand extension, it was found that it could have impact on parent brand while the consumers changed their attitude for these factors. Besides, Kwun (2010) also proved that consumers’ attitude toward parent brand could influence entire evaluation of family brands, and the attitude toward extended brand also could affect evaluation of extended brand.

The relationships among the variables the relationships among brand image, brand awareness, perceived quality and the attitude toward extended brand

Brand image and perceived quality were the important components of brand equity, and positively related with the performance in hotel industry and chain restaurants (Kim & Kim, 2005). The restaurant with better brand image means the brand image stronger and more positive than other restaurants. And, brand image would influence consumers’ behavior, so the restaurateurs paid more and more attention to the image of restaurants (Ryu, Han, & Kim, 2008). Kim and Kim (2004) found that brand awareness had the strongest effect on the sales revenue. Kim et al. (2008) proposed that brand awareness of the hotels could increase customers’ repurchasing intention, and consumers’ perceived quality had positive impact on repurchasing intention.

Consumers’ attitude toward extended brand was influenced by brand image, and brand image could affect consumers’ extended brand image and purchasing intention (Lin, 2006). Brand awareness also could affect consumers’ attitude toward extended brand, and parent brand awareness could affect consumers’ perceived value of extended brand (Lee & Jhu, 2013). Also, the quality of parent brand was imperative to the evaluation of extended brand (Lin, 2006; Milberg et al., 2013). Consequently, the relationship that brand image, brand awareness, perceived quality of parent brand positively influenced consumers’ attitude toward extended brand was supported.

The relationships between brand trust and the attitude toward extended brand

Hyun (2009) proposed that trust was a component of brand equity in chain restaurants. Brand trust was a psychological status of trustiness for a brand which could bring consumers security, and make the consumers believe this brand could meet their expectation (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Aleman, 2001). Brand trust could raise consumers’ brand loyalty, maintain competitive advantages and increase performance (Ha, 2004). Song, Hur and Kim (2012) addressed that brand trust could enhance brand loyalty behaviors and reduce perceived brand risk. Jin, Nathaniel, and Mabkhot, Shaari and Salleh (2017) proposed that brand trust is found to mediate the relationships between brand personality and brand loyalty. Wang, Chen, Lu and Ho (2019) addressed that brand trust was an important factor for consumers’ interaction with a brand in light food restaurants. Merkebu (2016) also proved the positive effect of brand trust on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in upscale restaurants. Additionally, a significantly positive relationship between brand experience and brand trust was proposed (Kang, Manthiou, Sumarjan, & Tang, 2017). The effect of brand trust could result in different performance of brand extension. Hence, brand trust will be applied as a moderating variable to explore the influential path in different models in this research.

The dimensions of brand trust included trustworthiness and the intention for the brand which could satisfy consumers’ need and intend to repurchase (Delgado-Ballester et al., 2003; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ganesan, 1994). While manipulating brand extension, it’s expected to apply brand trust to make the consumers trust the extended brand and increase purchasing intention. However, the research related with brand trust in hospitality industry was insufficient, it needs to be deeply explored.

The relationships between brand familiarity and the attitude toward extended brand

Brand familiarity is the knowledge for the brand in consumers’ mind (Campbell & Keller, 2003). Perreault and McCarthy (2002) proposed that brand familiarity is consumers’ understanding and preference for the brand. By holding product promotion or activity, it would increase consumers’ brand familiarity. If the consumers had higher brand familiarity, they could understand the product and service of the enterprise and have better brand evaluation (Hardesty, Carlson, & Bearden, 2002). It was held that brand familiarity and brand relevance would generate positive effect on the effectiveness of advertisements (Huang & Zhou, 2016). Additionally, the moderating role of brand familiarity in cross-media effects was proved (Huang, 2016).

The moderating effect of brand familiarity between the extended brand attitude and family brands was proved. When the consumers had higher brand familiarity, the effect of transferring from extended brand to family brands would be stronger (Kwun, 2010). Therefore, brand familiarity was taken as moderating variable to explore the relationships of parent brand, extended brand and family brands.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES

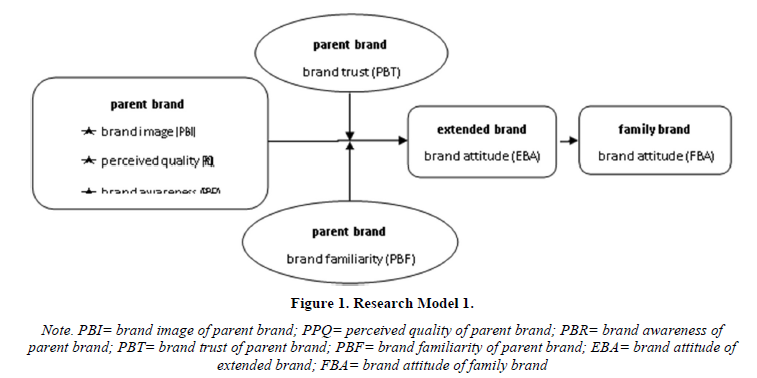

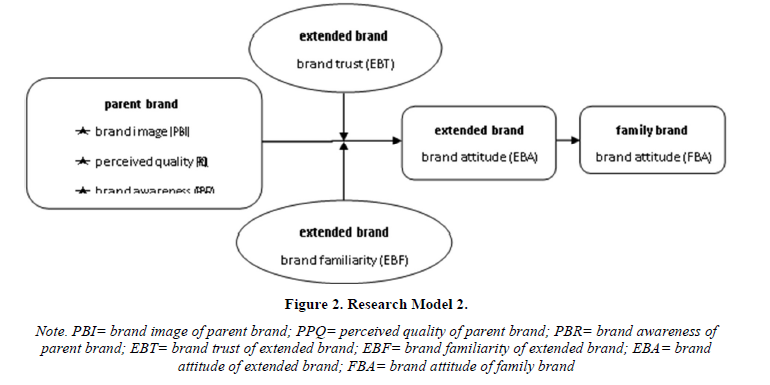

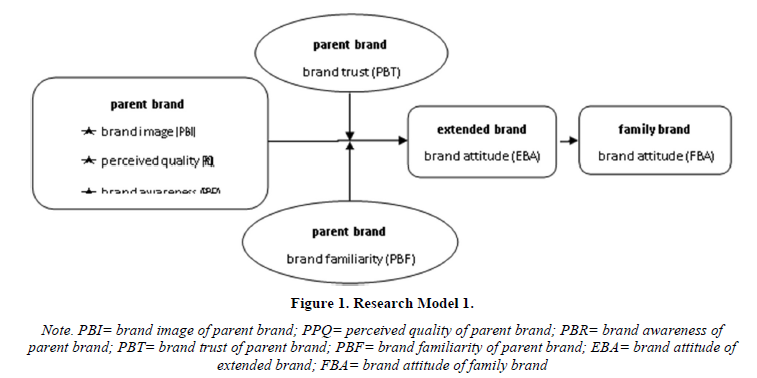

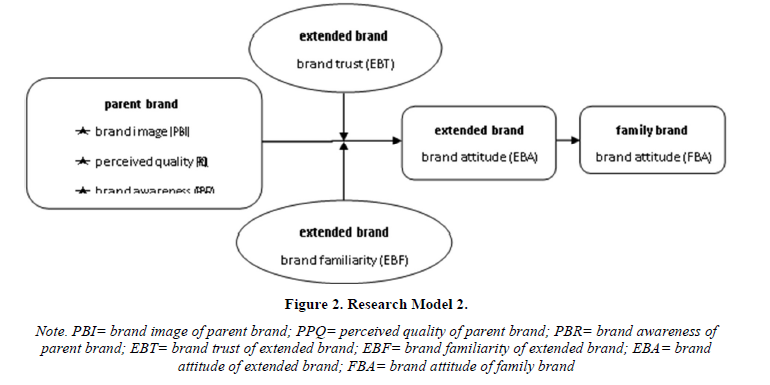

A quantitative research approach was applied in this research. To sum up the above, the independent variables were brand image, perceived quality and brand awareness of parent brand. The dependent variable was brand attitude of extended brand and family brands. For the conceptual frameworks of this research, there were two research models formed. In research model 1, brand trust and brand familiarity of parent brand were taken as the moderating variables (Figure 1). In research model 2, brand trust and brand familiarity of extended brand were taken as the moderating variables (Figure 2). In order to make the article more concise, the variables were represented in abbreviations as follows:

PBI: brand image of parent brand; PPQ: perceived quality of parent brand; PBR: brand awareness of parent brand; PBT: brand trust of parent brand; PBF: brand familiarity of parent brand; EBA: brand attitude of extended brand; FBA: brand attitude of family brandss; EBT: brand trust of extended brand; EBF: brand familiarity of extended brand

According to the research model 1, the present study led to the hypotheses: Hypothesis 1 (H1): PBI positively influenced EBA.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): PPQ positively influenced EBA. Hypothesis 3 (H3): PBR positively influenced EBA. Hypothesis 4 (H4): EBA positively influenced FBA. Hypothesis 5 (H5): PBI positively influenced FBA. Hypothesis 6 (H6): PPQ positively influenced FBA. Hypothesis 7 (H7): PBR positively influenced FBA.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): EBA had mediating effect between PBI and FBA. Hypothesis 9 (H9): EBA had mediating effect between PPQ and FBA. Hypothesis 10 (H10): EBA had mediating effect between PBR and FBA. Hypothesis 11 (H11): PBT had moderating effect between PBI and EBA. Hypothesis 12 (H12): PBT had moderating effect between PPQ and EBA. Hypothesis 13 (H13): PBT had moderating effect between PBR and EBA. Hypothesis 14 (H14): PBF had moderating effect between PBI and EBA. Hypothesis 15 (H15): PBF had moderating effect between PPQ and EBA. Hypothesis 16 (H16): PBF had moderating effect between PBR and EBA.

The main difference between research model 1 and model 2 was applying brand trust and brand familiarity of extended brand in research model 2 as the moderating variables. Therefore, the present study led to the hypotheses 1 to 16 which were the same as those of research model 1, and the following hypotheses (H17 to H22):

Hypothesis 17 (H17): EBT had moderating effect between PBI and EBA. Hypothesis 18 (H18): EBT had moderating effect between PPQ and EBA. Hypothesis 19 (H19): EBT had moderating effect between PBR and EBA. Hypothesis 20 (H20): EBF had moderating effect between PBI and EBA. Hypothesis 21 (H21): EBF had moderating effect between PPQ and EBA. Hypothesis 22 (H22): EBF had moderating effect between PBR and EBA.

METHODOLOGY

Measurement tools

The relationships among parent brand, extended brand and family brands were explored in this research. Before answering the questionnaire, the respondents need to verify and select the restaurants he/she ever visited, including a parent brand restaurant and one of its extended brand restaurants which belonged to the same group. The language used in the questionnaire was traditional Chinese. Regarding the translation, a back translation method was employed to verify wording and meaning of each question of the measurement. A questionnaire in traditional Chinese was translated into English to verify the original meanings.

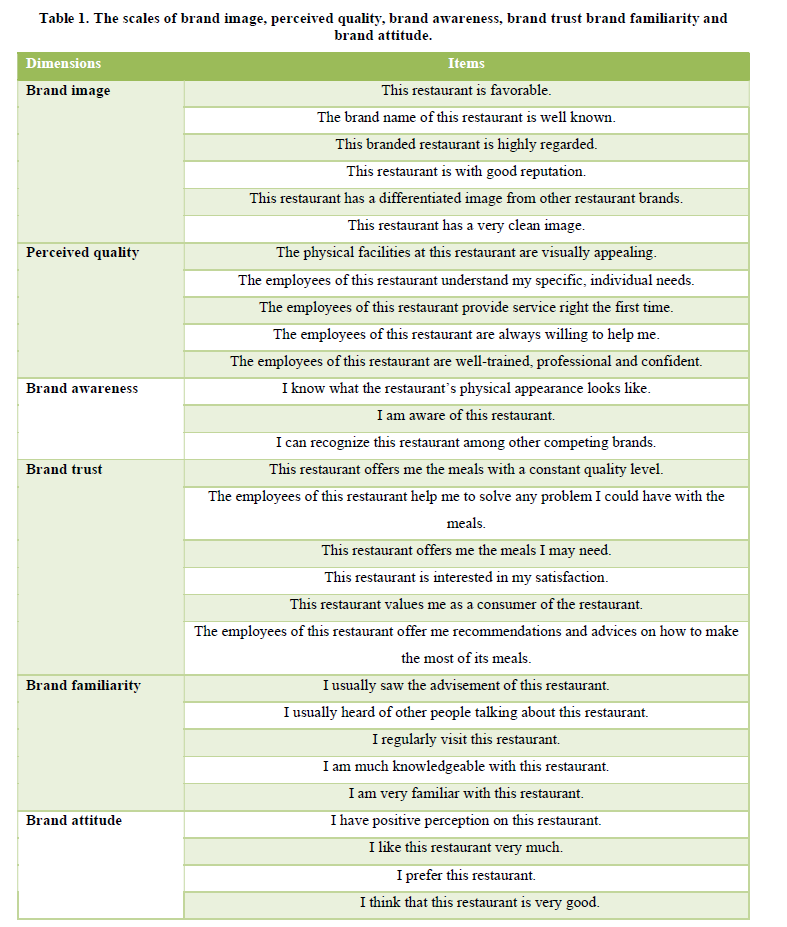

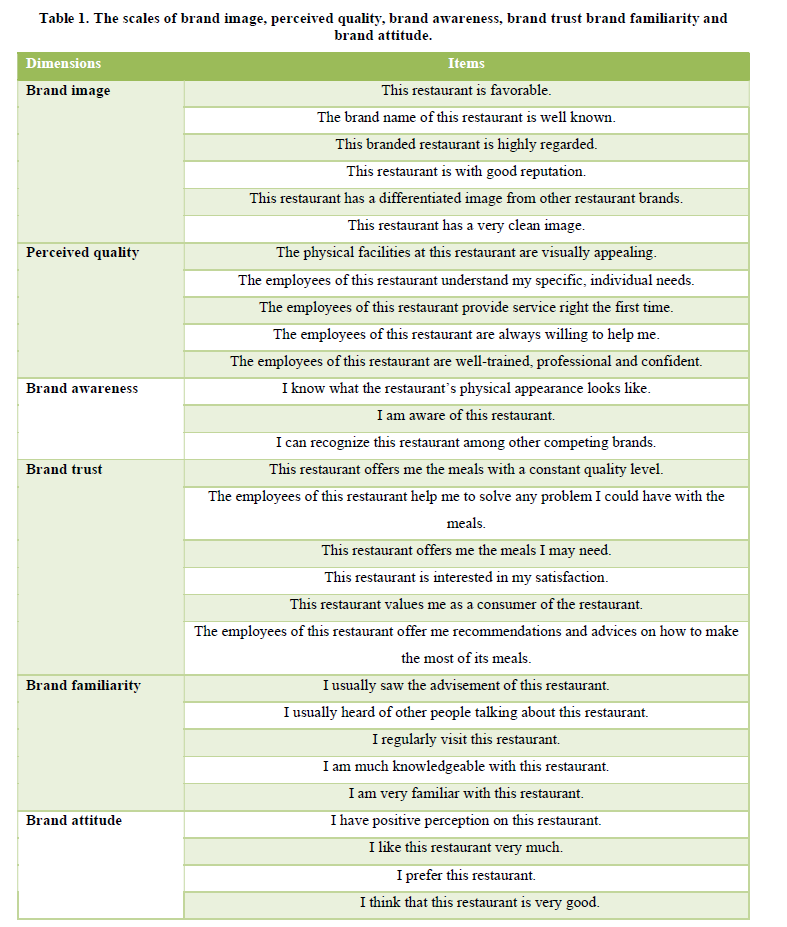

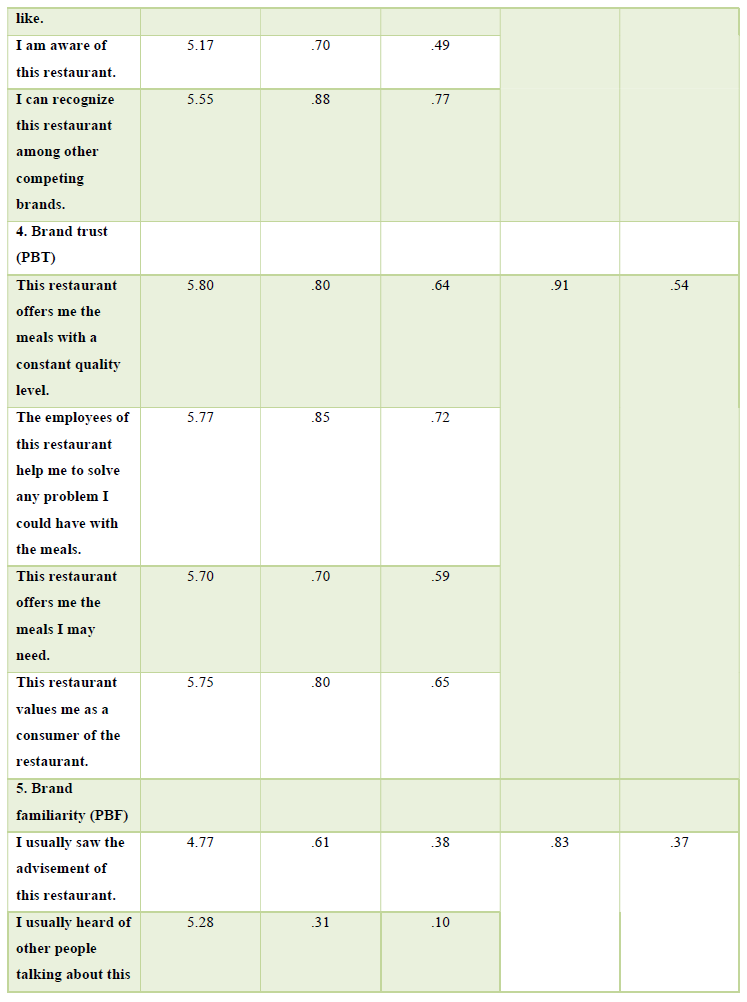

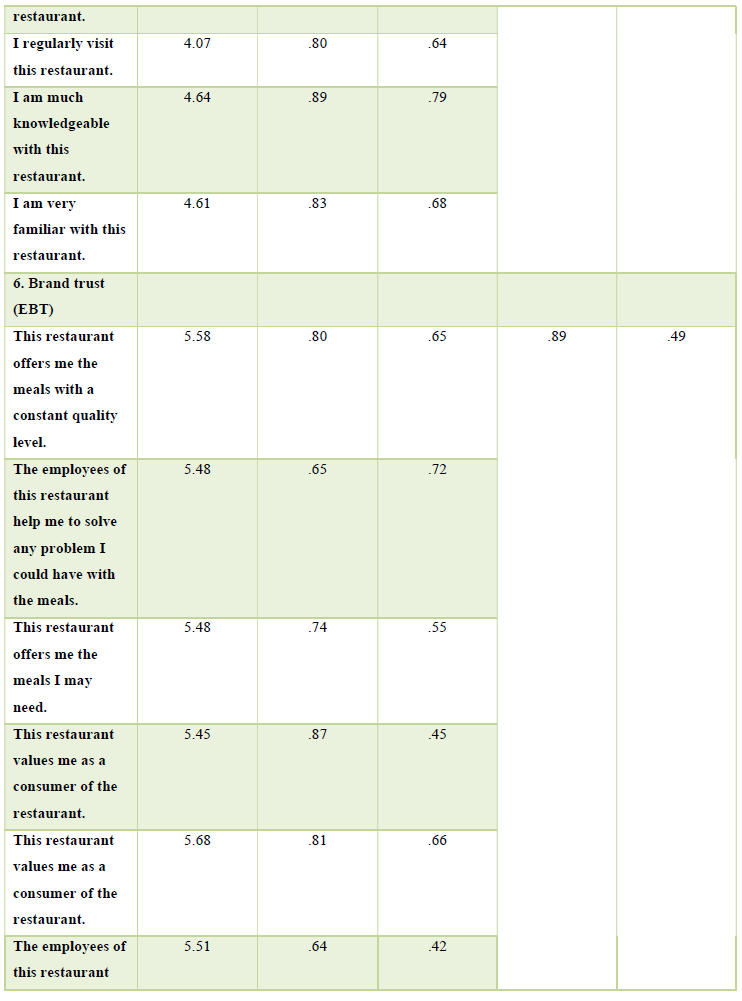

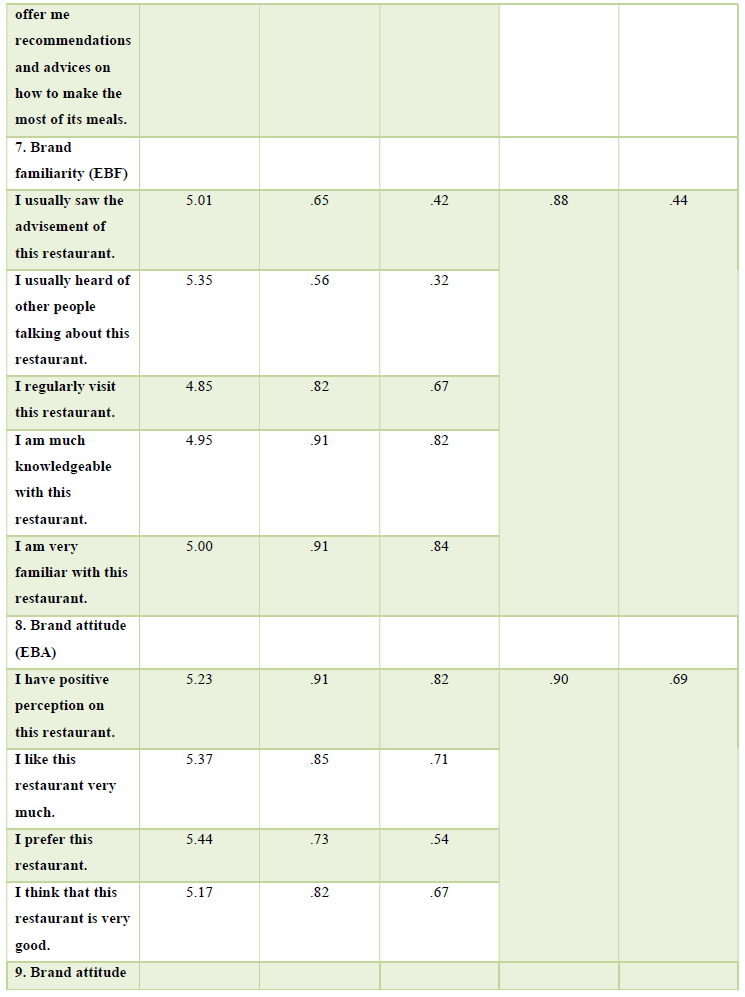

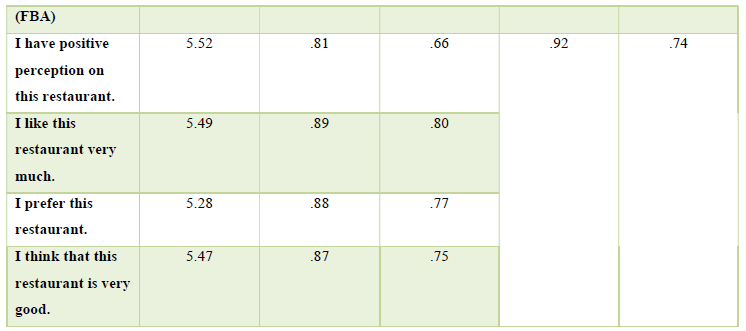

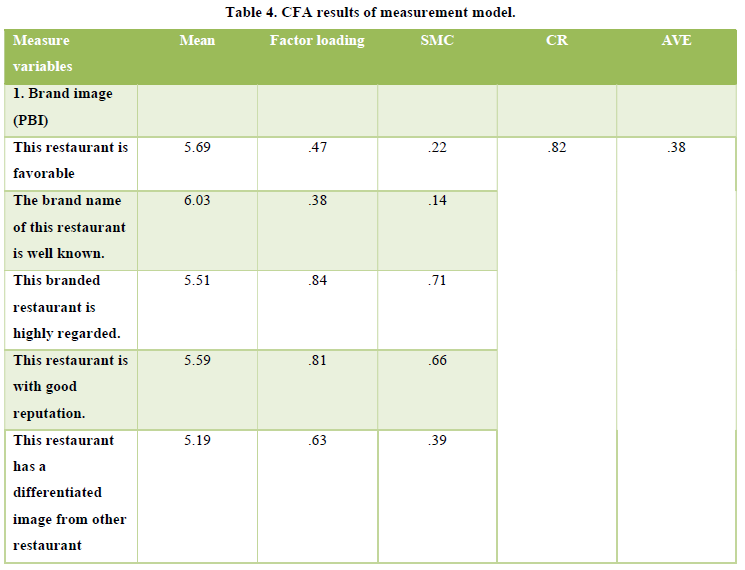

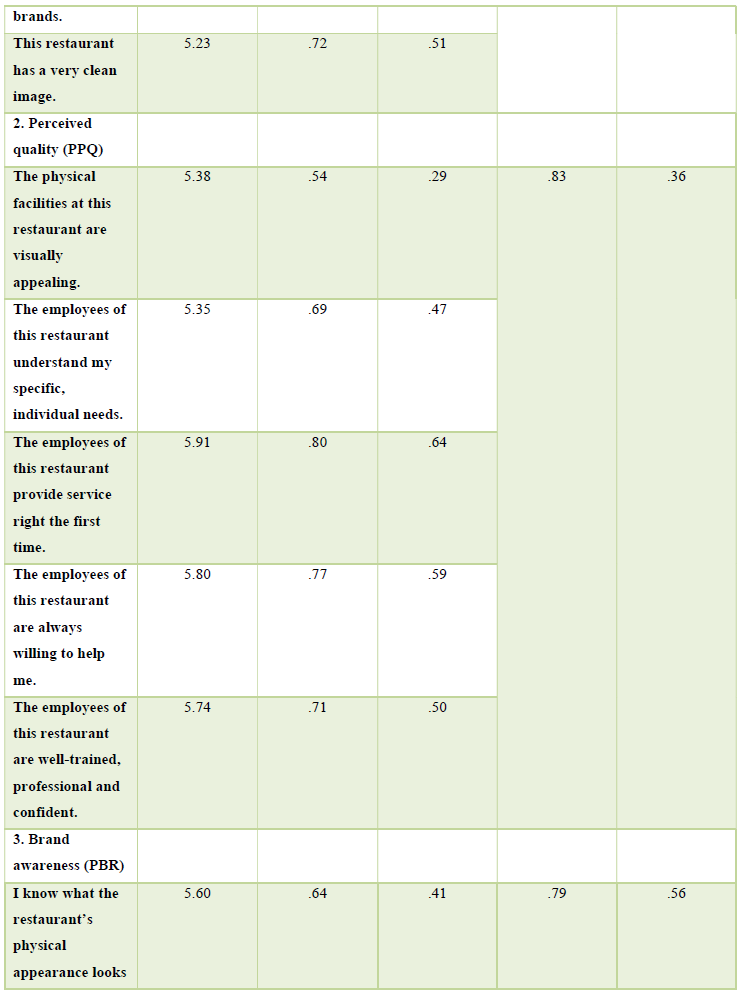

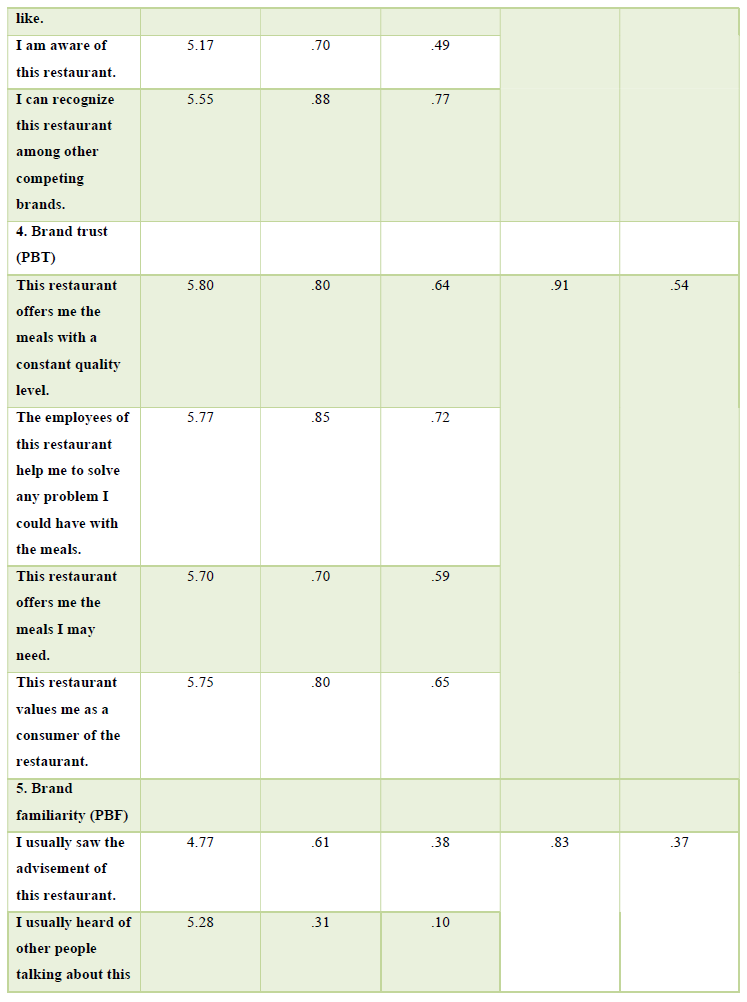

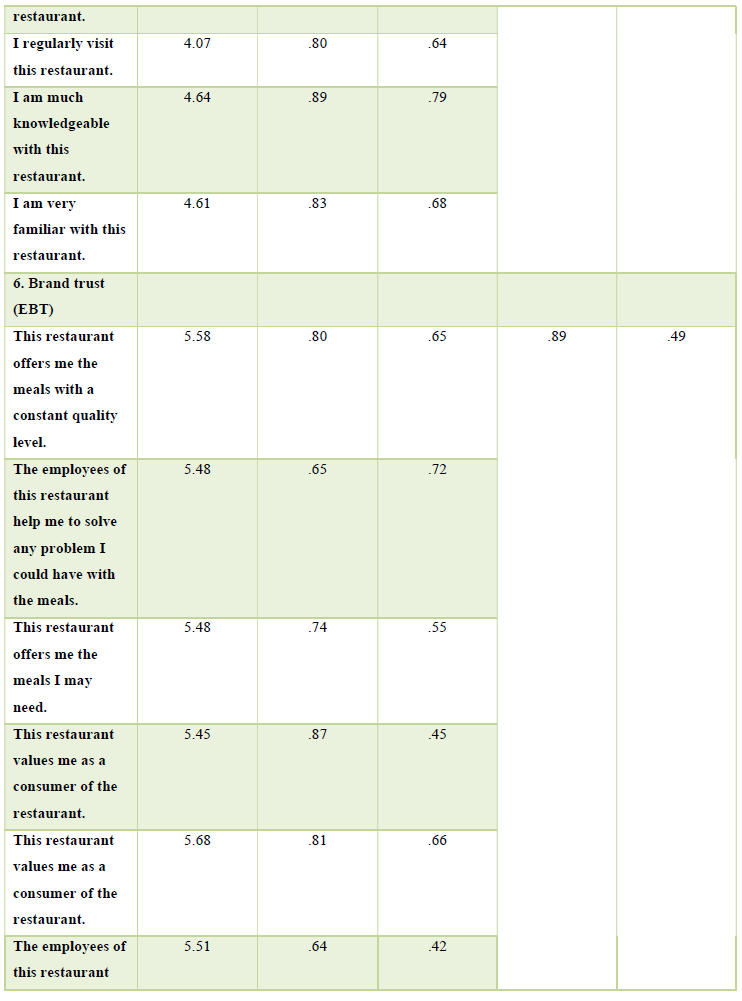

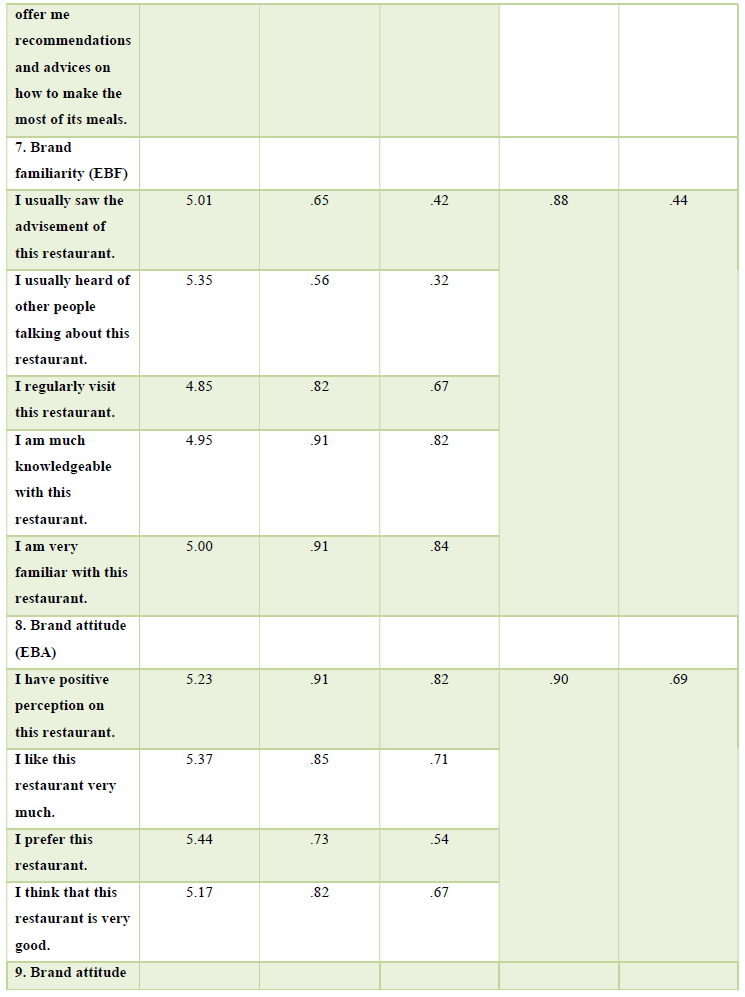

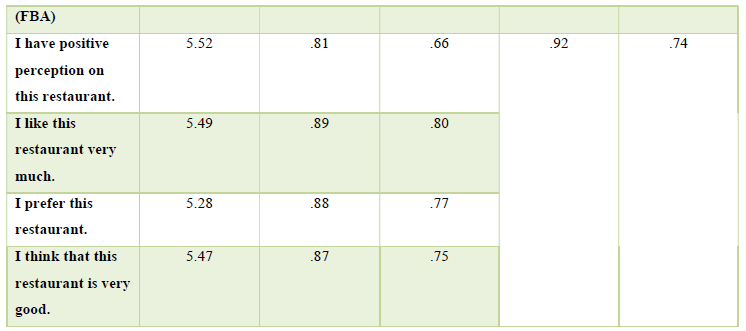

Focused on chain restaurants, the measurement tools included 10 parts: part 1 to part 5 were brand image, perceived quality, brand awareness, brand trust, brand familiarity of parent brand restaurant respectively, part 6 to 8 were brand trust, brand familiarity and brand attitude of extended brand restaurant respectively, part 9 was brand attitude of brand family, and part 10 was respondents’ demographics information. The 7-point Likert-type was used in these scales, from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” (from 7 to 1 points). The questionnaire gathered respondents’ demographic information (such as gender, age, marital status, educational level, occupation and monthly income) and the frequency of eating out (by weekly). The scale of brand image (6 items) was referred and modified from Chiang and Jang (2006), Kim and Kim (2005) and Tsai (2005). The scale of perceived quality (5 items) was referred and modified from Kim et al. (2008). The scale of brand awareness (3 items) was referred and modified from Kim et al. (2008). The scale of brand trust (6 items) was referred and modified from Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Aleman (2001). The scale of brand familiarity (5 items) was referred and modified from Alba and Hutchinson (1987) and Kwun (2010). The scale of brand attitude (4 items) was referred and modified from Kwun (2010). Please refer to Table 1.

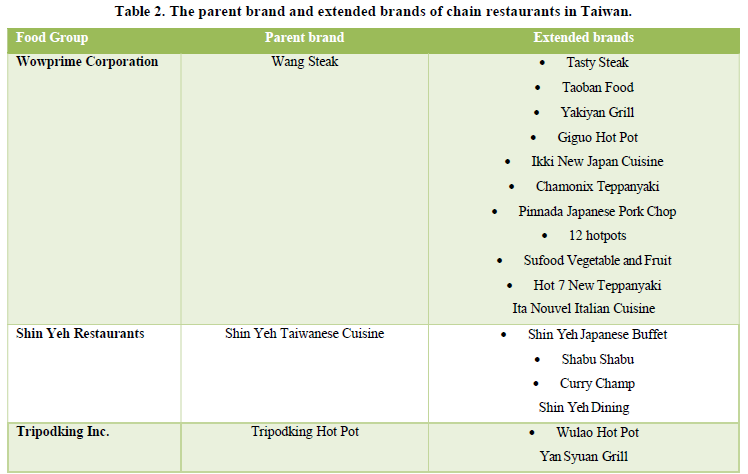

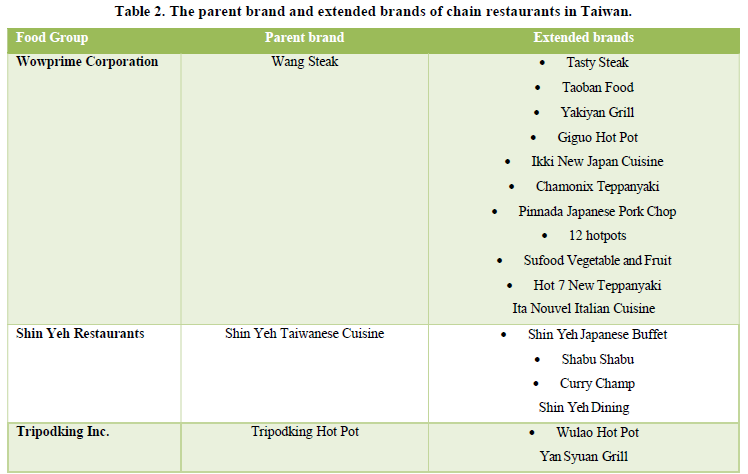

Sampling design

The chain restaurants which implemented brand extension in Taiwan included Wowprime Corporation, Shin Yeh Restaurants, Tripodking Inc. The customers who ever had dining experience in the restaurant of parent brand and any restaurant of extended brand that were belonged to the same group were taken as the objects in this research. By cooperating with the restaurateurs, the interviewers distributed the questionnaires in one of the extended-brand restaurants. Before distributing the questionnaires, they need to ask the interviewees if they ever had dining experience in the parent-brand restaurant. The purposive sampling was employed to select the chain restaurants, and the convenience sampling was used to proceed the questionnaire distribution. The sample size was determined by the question items of the scales, around 10 times of the items were appropriate (Roscoe, 1975). The parent brand and extended brand of chain restaurants in Taiwan were listed in Table 2.

Data analysis

The analyzing tool is SPSS for Windows 20.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Science). Reliability analysis was utilized to understand internal consistency of the variables. Descriptive statistics was employed to understand the structure of respondents. To test the hypotheses, we conducted a bootstrapping analysis for moderated mediation developed by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007) using the PROCESS macro in SPSS for Model 4 and Model 9 (Hayes, 2012).

THE FINDINGS

Respondents’ profile

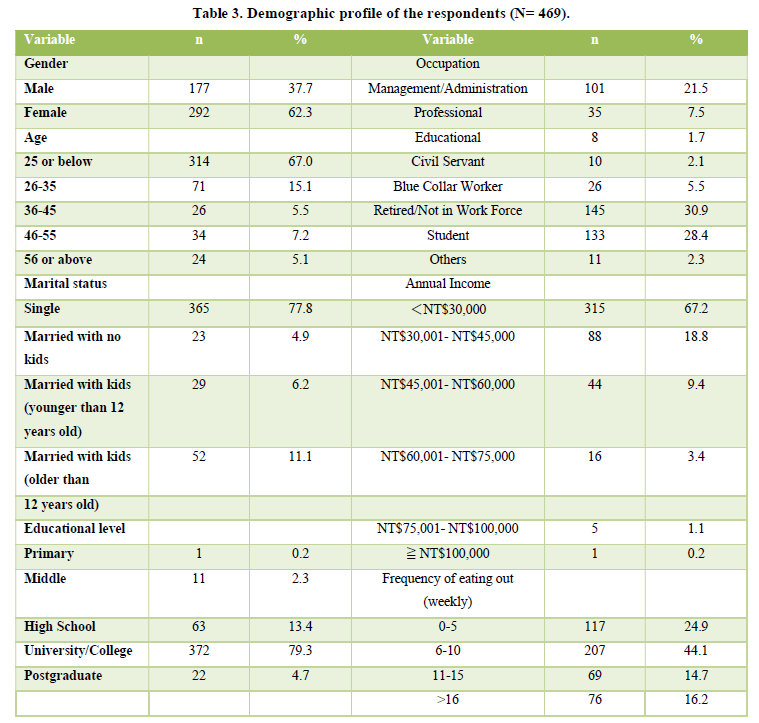

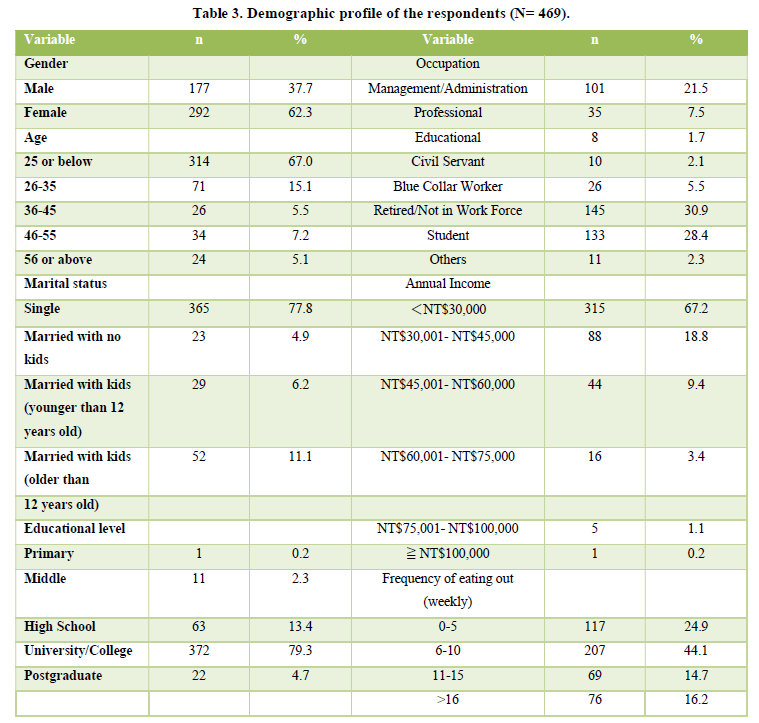

A total of 550 questionnaires were distributed and 469 valid responses were obtained after removing incomplete samples, yielding a response rate of 85.3%. As illustrated in Table 3, the majority of respondents were female (61.3%). Furthermore, 67.0% of respondents were aged younger than 25 years old, and 15.1% were aged between 26 and 35 years old. Moreover, 79.3% of respondents had bachelor degree and 30.9% of respondents were retired or not in work force. Additionally, 67.2% of respondents had annual income of less than 15,000 USD per year, and 18.8% had income of between 15,000 to 29,999 USD per year. Finally, most respondents’ frequency of eating out was 6-10 times a week (44.1%) (Table 3).

Results of data analysis

There were two research models formed in this research. The results of data analysis for the two models were presented as follows.

Test of reliability and validity

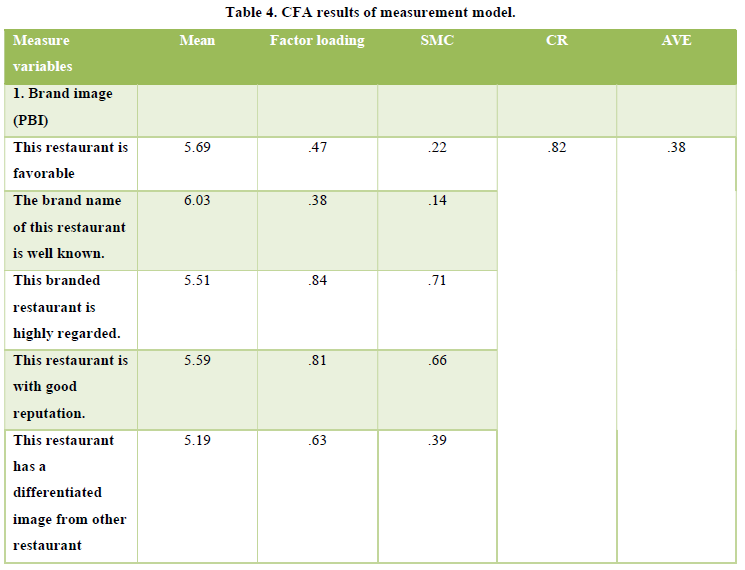

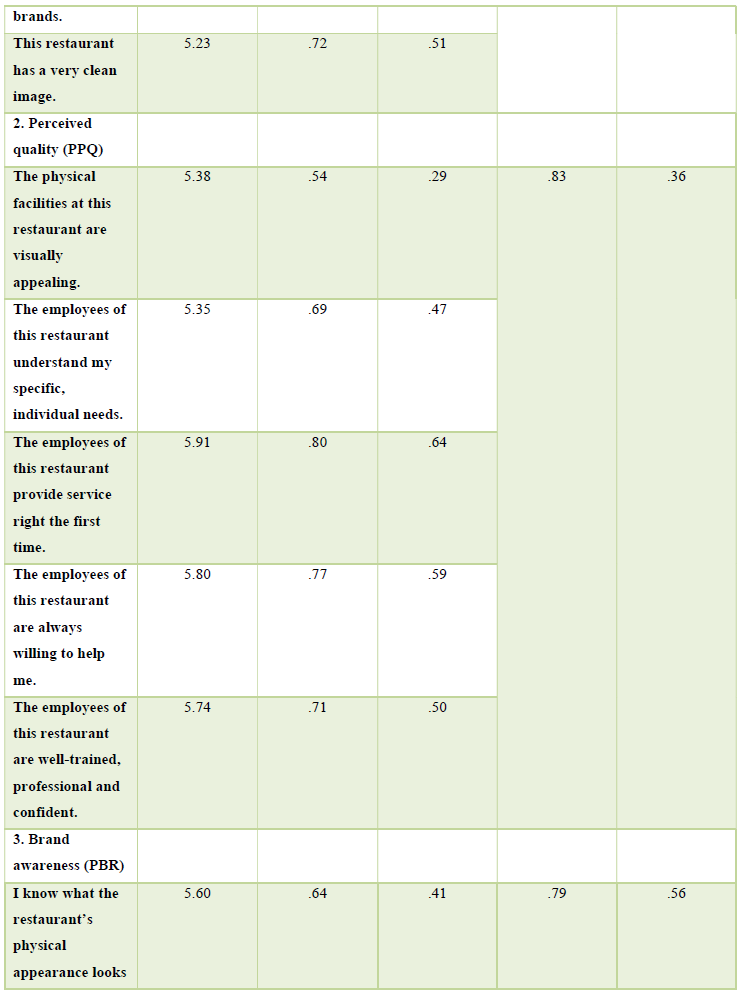

Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated to determine the credibility of the scales and each of their constructs. Ideally, Cronbach’s α should be higher than 0.70 (DeVellis, 1991; Nunnally, 1978). For parent brand, the Cronbach’s α of PBI, PPQ, PBR was 0.831, 0.905 and 0.751 respectively. The Cronbach’s α of PBT and PBF was 0.865 and 0.808. For extended brand, the Cronbach’s α of EBA, EBT and EBF was 0.944, 0.891 and 0.883 respectively. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s α of FBA was 0.950. These results equal to or larger than ideal value suggested that each component had acceptable credibility. Furthermore, the proposed measurement model was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The results showed that the composite reliability of the seven latent variables ranged between 0.79 and 0.92; thus, all were above 0.7 threshold (Fornell & Larcker 1981; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2009). The average variances extracted (AVE) reflected the overall variance in the indicators that was explained by the latent construct. The AVEs of most dimensions were higher than 0.50, it revealed that each scale had acceptable convergent validity (Table 4).

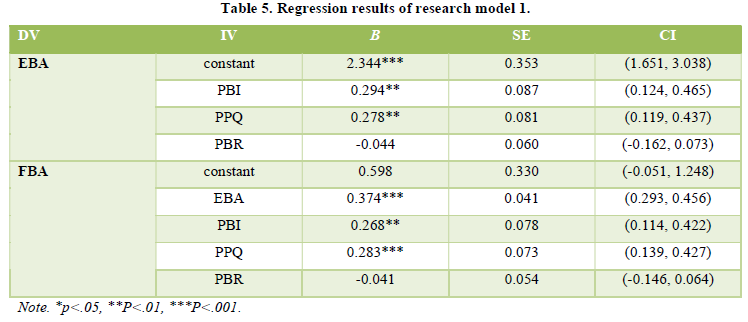

The results of research model 1

In research model 1, PBI, PPQ and PBR were independent variables, FBA was the dependent variable; and EBA was the mediating variable, PBT and PBF were the moderating variables. The research model 1 included mediation and moderation model. Therefore, at first, to proceed the examination of mediating effect, then to proceed the examination of moderating effect. The PROCESS software was employed in the data analysis (Hayes, 2012). The model 4 of PROCESS was applied in the analysis of indirect effect. Owing to there was no intervention, the model 9 of PROCESS was used to proceed data analysis. The findings revealed that PBI and PPQ had significant influence on EBA (β=0.294, SE=0.087, p<.01; β=0.278, SE=0.081, p<.01), whereas PBR didn’t have significant influence on EBA (β=-0.044, SE=0.060, p>.05). For FBA, PBI, PPQ and EBA had significant influence on FBA (β=0.374, SE=0.041, p<.001; β=0.268, SE=0.078, p<.01; β=0.283, SE=0.073, p<.001), whereas

PBR didn’t have significant influence on FBA (β=-0.041, SE=0.054, p>.05) (Table 5).

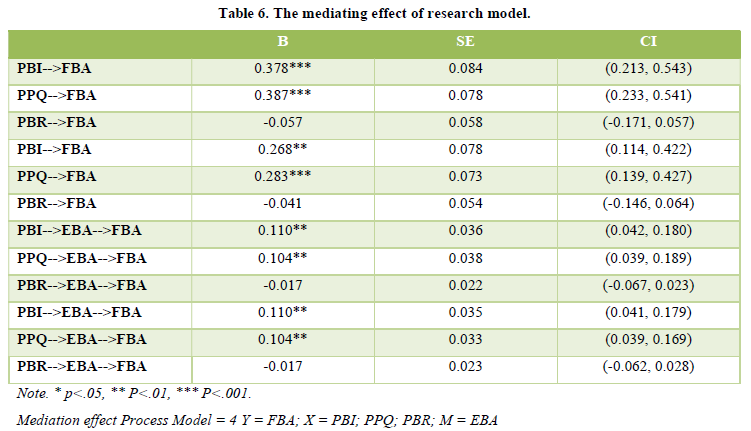

Regarding the mediating effect in research model 1, the total effect is the sum of direct effect and indirect effect. According to table 6, such as, for the total effect of PBI on FBA, it’s 0.378, which is equal to the sum of 0.268 and 0.110. According to the findings, two indirect effects were proved, which were the total effect of PBI on FBA (PBI-->EBA-->FBA) and the total effect of PPQ on FBA (PPQ-->EBA-->FBA). And, the p value is less than 0.05, the sobel test revealed that the confidence interval didn’t include 0 which was significant. Regarding the mediating effect, the findings showed that EBA had mediating effect on the relationship of PBI and FBA, and also on the relationship of PPQ and FBA (Table 6).

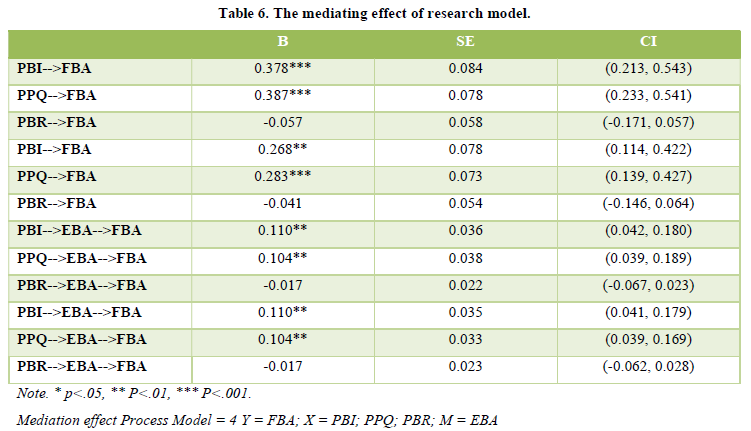

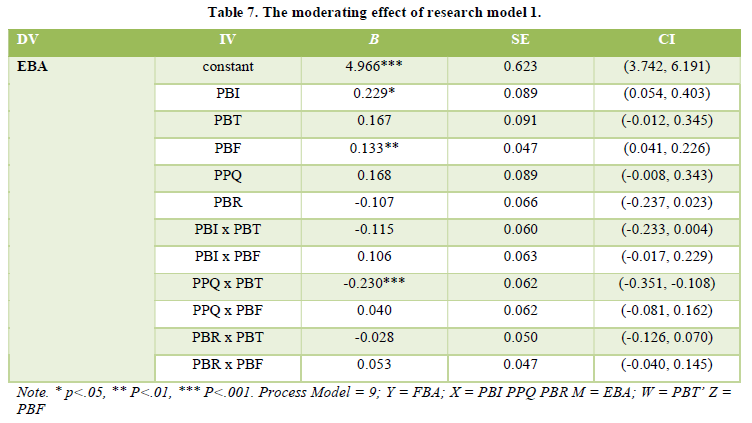

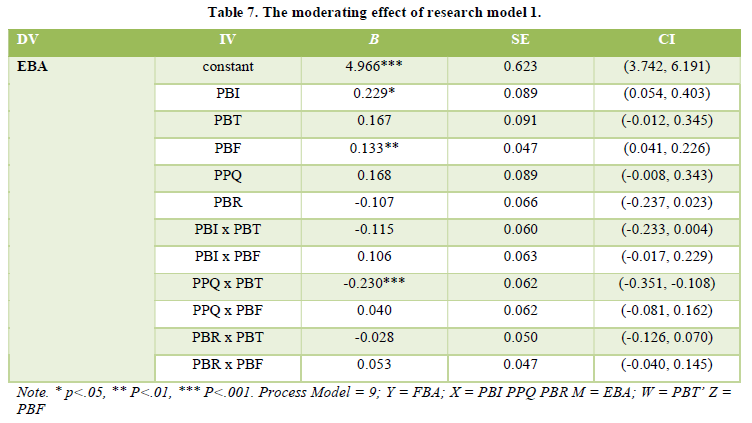

While completing the examination of mediating effect, next, the moderating effect was examined. The PROCESS model 9 was employed. There were three independent variables- PBI, PPQ and PBR and two moderating variables- PBT and PBF, hence, there were six moderating effects needed to be analyzed. According to the table 7, the results revealed that one moderating effect- PPQ x PBT was supported. Namely, the PBT had moderating effect on the relationship of PPQ and EBA, whereas PBF didn’t have moderating effect on the relationship of PPQ and EBA (Table 7).

The results of research model 2

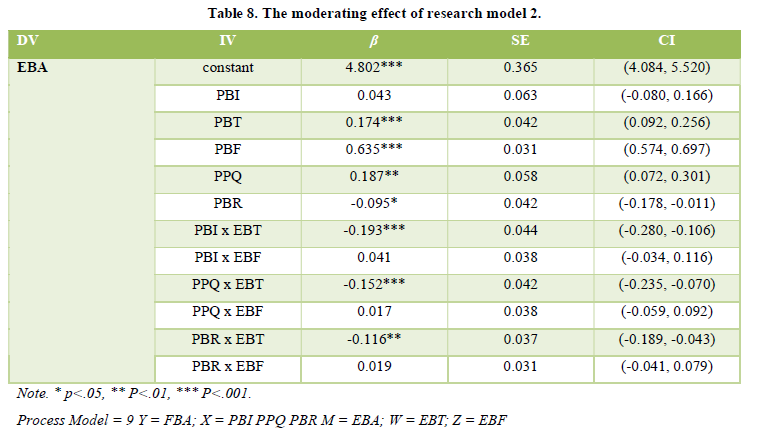

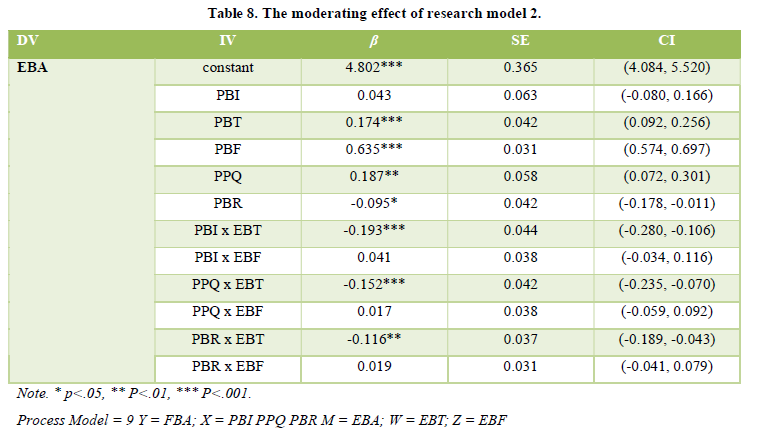

In research model 2, the three independent variables were PBI, PPQ and PBR, and the moderating variables were EBT and EBF. The mediating effect was the same as those of model 1. In research model 2, there were six moderating effects to be examined. According to table 8, the results revealed that three moderating effects- PBI x EBT, PPQ x EBT and PBR x EBT were supported. Namely, the EBT had moderating effect on the relationships of PBI and EBA, PPQ and EBA, and PBR and EBA, whereas EBF didn’t have moderating effect on the relationships of PBI, PPQ, PBR and EBA (Table 8).

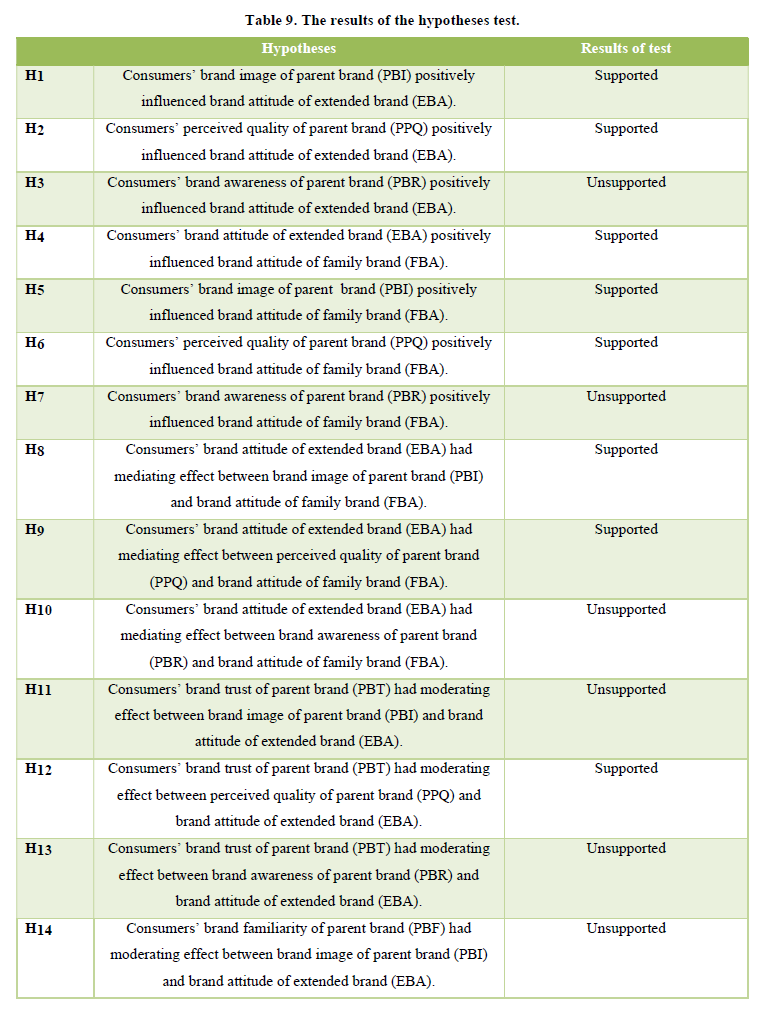

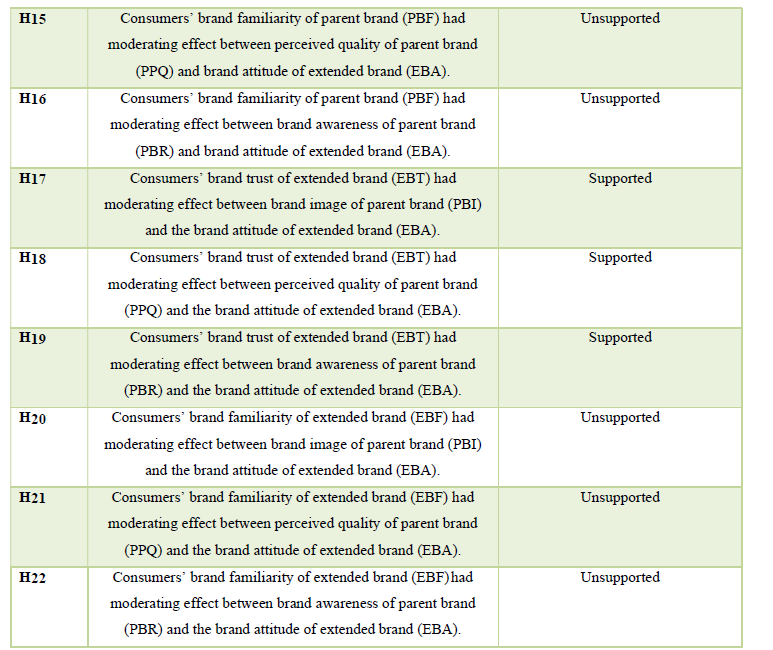

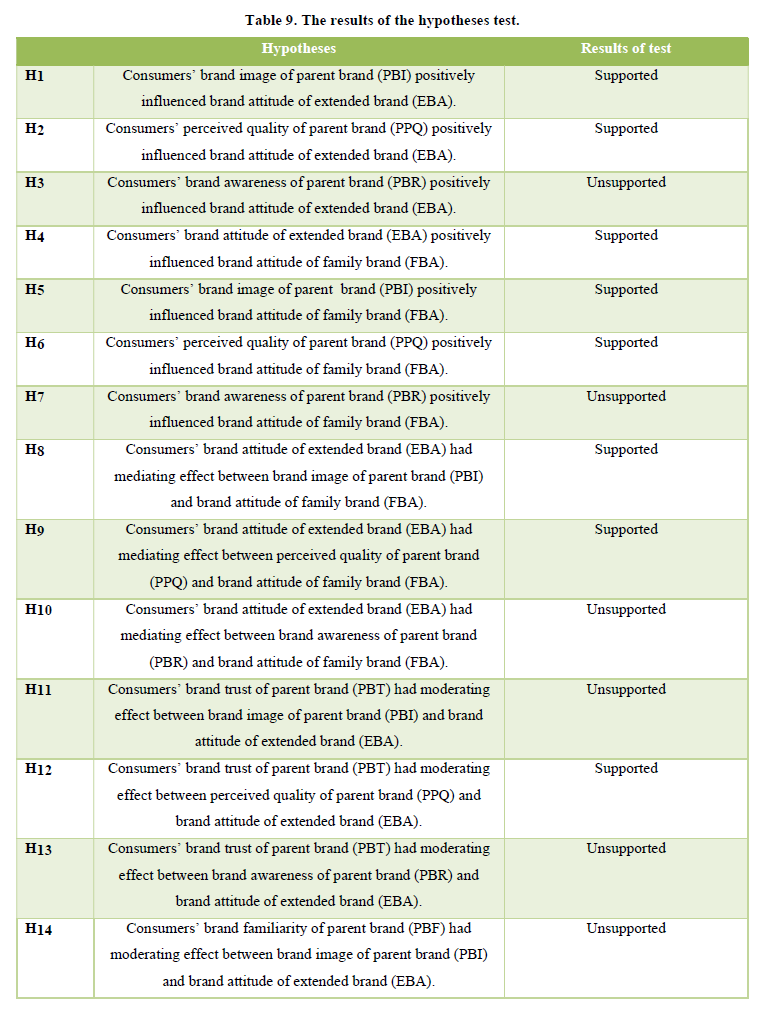

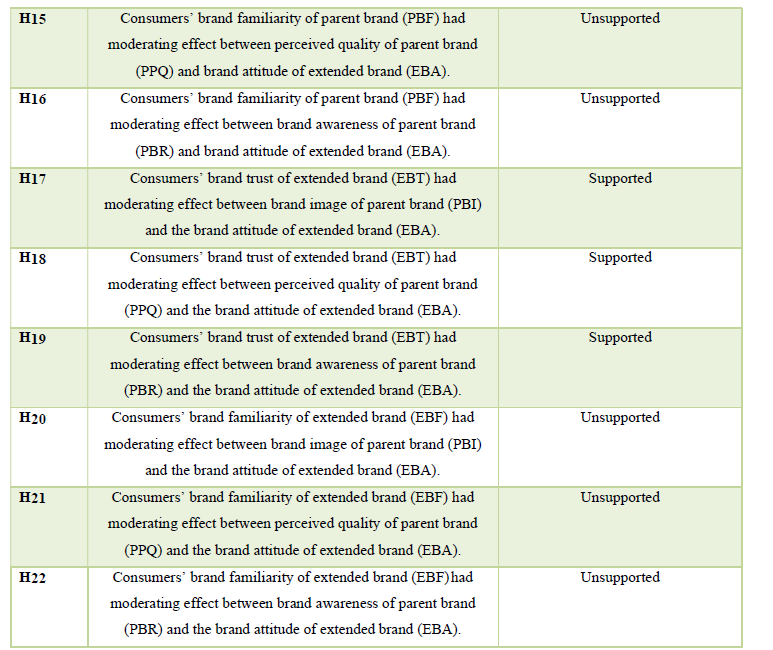

In this research, the twenty-two hypotheses for two research models were examined. According to data analysis, the results of the hypothesis test were listed in Table 9.

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

Conclusions

In this research, two research models were examined. In these two research models, the independent variables were brand image (PBI), perceived quality (PPQ) and brand awareness (PBR) of parent brand, the dependent variable was brand attitude of family brands (FBA), and the mediating variable was brand attitude of extended brand (EBA). In research model 1, brand trust of parent brand (PBT) and brand familiarity of parent brand (PBF) were moderating variables. In research model 2, brand trust of extended brand (EBT) and brand familiarity of extended brand (EBF) were moderating variables. Through the examination of two research models, the impact of brand image, perceived quality and brand awareness of parent brand on brand attitude of extended brand and family brands was proved. And, the roles of brand trust and brand familiarity on the relationship of parent brand and extended brand, family brands were explored and clarified.

According to the findings, brand image (PBI) and perceived quality (PPQ) of parent brand had significantly positive influence on the brand attitude of extended brand (EBA) and brand attitude of family brands (FBA). Brand image and perceived quality had significantly positive influence on brand attitude, it coincided with that of previous research (Milberg et al., 2013; Lin, 2006). In this research, it was explored further for the impact of brand image and perceived quality of parent brand on brand attitude of extended brand. However, for the impact of brand awareness on brand attitude, it was not proved in this research which was different from the results of previous research (Lee & Jhu, 2013). The brand awareness of parent brand didn’t have significantly positive influence on brand attitude of extended brand. While employing brand extension, it was usually expected to utilize brand awareness of parent brand to make the consumers have better brand attitude toward extended brand. In this research, it was found that brand image and perceived quality of parent brand were crucial to consumers’ attitude. For the family brands, brand image and perceived quality of parent brand had significantly positive influence on brand attitude of family brands, whereas the brand awareness of parent brand didn’t.

The influence of brand attitude was also examined. It showed that the brand attitude of extended brand (EBA) had significantly positive influence on brand attitude of family brands (FBA). It coincided with Kwun’s (2010), proposing that consumers’ attitude toward parent brand could influence the entire evaluation of family brands. Regarding the mediating effect of brand attitude of extended brand, it was found that the brand attitude of extended brand (EBA) had mediating effect on the relationship of brand image (PBI), perceived quality (PPQ) of parent brand and brand attitude of family brands (FBA). It meant that brand image, perceived quality of parent brand could have positive influence on brand attitude of family brands through the impact of brand attitude of extended brand. It revealed that brand attitude of extended brand was important to brand extension.

For the moderating effect, it was proved that brand trust of parent brand (PBT) had moderating effect on the relationship of perceived quality of parent brand (PPQ) and brand attitude of extended brand (EBA). As regards with the moderating effect of brand trust of extended brand (EBT), it revealed that the brand trust of extended brand (EBT) had moderating effect on the relationship of brand image (PBI), perceived quality (PPQ) and brand awareness (PBR) of parent brand and brand attitude of extended brand (EBA). It showed that brand trust did have significant influence on the relationship of parent brand and extended brand.

To summarize the findings of this research, several conclusions could be proposed for the exploration of brand extension. Based on the findings, regarding brand awareness, it was not a key factor influencing brand attitude. The parent brand awareness didn’t significantly influence brand attitude of extended brand and family brands. This finding was different from previous research addressing that parent brand awareness could affect consumers’ perceived value on extended brand (Lee & Jhu, 2013). The other findings argued that brand image and perceived quality significantly influenced brand attitude of family brands. It revealed that the key factors affecting the effect of brand extension were brand image and perceived quality. Namely, even though a parent brand was very popular and famous for the public, maintaining good brand image and service quality were still crucial to the success of band extension.

From the examination of mediating effect, the extended brand attitude had significantly mediating effect between parent brand image and brand attitude of family brandss, also significant between perceived quality of parent brand and brand attitude of family brandss, not significant between brand awareness of parent brand and brand attitude of family brandss. It meant that parent brand image and perceived quality could affect brand attitude of family brandss through extended brand attitude. Thus, brand image and perceived quality of parent brand were key factors affecting consumers’ attitude toward family brands.

Regarding the examination of moderating effect, it was proved that brand trust of extended brand had significantly moderating effect between parent brand (including brand image, perceived quality and brand awareness) and extended brand attitude. It showed if consumers’ trust was damaged by extended brand, the original effect of parent brand could be diminished; on the contrary, if consumers’ trust was promoted by extended brand, the effect of parent brand would be enhanced. The role of brand trust for brand extension was emphasized in this research.

Suggestions

In this research, brand trust and brand familiarity were employed to explore the relationship of parent brand and extended brand in foodservice industry. The role of brand trust for brand extension was clarified in this research. For brand trust of parent brand and brand trust of extended brand, both of them had moderating effect between perceived quality of parent brand and brand attitude of extended brand. It revealed that perceived quality of parent brand was affected by brand trust of parent brand and extended brand. It meant that the quality provided by the restaurant of parent brand indeed had impact on customers’ trust for the restaurant of parent brand and extended brand. While planning to launch brand extension, the restaurateurs need to keep in mind that maintaining and improving quality was crucial to the success of brand extension. In addition, while implementing the strategy of band extension to access different market segment, utilizing brand trust of parent brand was as important as maintaining and improving brand trust of extended brand. Otherwise, it could cause customers’ negative brand attitude as brand dilution which was addressed by Loken and Roedder (1993).

Brand trust of extended brand also had moderating effect between brand image, perceived quality, brand awareness of parent brand and brand attitude of extended brand. It showed that brand trust of extended brand was as important as brand trust of parent brand. Moreover, its impact could be more evident than that of parent brand. Therefore, while employing the strategy of brand extension to extend the market, the enterprise needs to realize its negative impact. If the extended brand was well performed to be with good brand trust, it could have mutually beneficial influence between parent brand and extended brand. Conversely, if the extended brand was not well performed, it could damage the parent brand; namely, the brand dilution was caused (Loken & Roedder, 1993). In this research, the role of brand trust was proved to be imperative to prevent brand dilution.

While reviewing the food safety events of past decade in Taiwan, the issue of food safety influenced consumers’ perception on the quality provided by the restaurant. If there was any negative report regarding food safety, it did damage consumers’ trust on the brand of foodservice industry. Especially while implementing brand extension, whether the food safety problem occurring in parent brand or extended brand, it could damage consumers’ trust on parent brand, extended brand and even the whole family brands. It was proved in this research. This key success factor for brand extension was emerged in this research. It also provided important implications for the industry. Brand familiarity was the other moderating variable in this research; however, it was not proved in the two research models. It revealed different findings from previous research (Kwun, 2010). Even though brand familiarity was a main motivator for the enterprise to launch brand extension, it couldn’t prolong its advantages if the brand image, perceived quality and brand trust were not maintained or improved.

To sum up the above, it was suggested that brand image and perceived quality were crucial to brand establishment and development of an enterprise. By providing quality service and building good brand image, it was the most important way to the success of a brand. Thus, it could obtain customers’ trust on the brand. The findings of this research revealed that brand trust was a factor affecting the impact of brand image, perceived quality on brand attitude. Furthermore, while promoting brand extension, brand trust was a factor which need to be emphasized. The enterprise needs to maintain and even promote brand trust while developing extended brand. Nowadays the enterprise tended to employ line extension to launch a new product by using the existed brand into a new market segment, especially for down-line extension to develop a brand with lower-price product. The effect of brand awareness and brand familiarity couldn’t be kept prolonged for brand extension. It was the most important for an enterprise to offer quality products and quality service to establish good brand image and obtain brand trust to facilitate sustainable development of family brands.

In this research, the role of brand trust was deeply explored while implementing brand extension. The findings help understand more on the role of brand trust for brand extension. It’ll be beneficial to the theory development of brand extension. And, while facing the issue of food safety, the solid suggestions proposed for brand extension implementation will facilitate appropriate brand extension to increase the entire benefit of family brands.

The limitation of this research was the questionnaire distribution. Owing to the limited budget and labor cost, the survey was implemented in the Northern Taiwan. The other area of Taiwan was hard to be accessed. Finally, for the direction of future research, the model of this research could be applied to other enterprises such as lodging industry. Especially, it could be focused on the difference between up extension and down extension; such as the parent brand is luxury hotel extending its brand to establish economic hotel, and vice versa. Further research identifying and testing the influential mechanism is expected.

- Aaker, D.A. (1990). Brand extensions: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Sloan Management Review 31(4): 47-56.

- Aaker, D.A., & Keller, K.L. (1990). Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing 54: 27-41.

- Alba, J.W., & Hutchinson, J.W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research 13(4): 411-435.

- Andaleeb, S.S. (1992). The trust concept: Research issues for channels of distribution. In N. S. Jagdish (Ed). Research in Marketing (Vol. 11). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Assael, H. (1998). Consumer behaviour and marketing action. Ohio: South-Western College Publishing.

- Bei, L.-T., & Cheng, S. (2004). The factors of endorsing effects in corporate umbrella branding strategies. Sun Yat-Sen Management Review 12(2): 269-305.

- Bhat, S., & Reddy, S.K. (1997). Investigating the dimensions of fit between a brand and its extension. Paper presented at the AMA 1997 Winter Educators’ Conference, Chicago, IL.

- Boo, H.C., & Mattila, A.S. (2002). A hotel restaurant brand alliance model: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Foodservice Business Research 5(2): 5-23.

- Broniarczyk, S., & Alba, J. (1994). The importance of the brand in brand extension. Journal of Marketing Research 31(2): 214-228.

- Burmann, C., Jost-Benz, M., & Riley, N. (2009). Towards an identity-based brand equity model. Journal of Business Research 62(3): 390-397.

- Campbell, M.C., & Keller, K.L. (2003). Brand familiarity and advertising repetition effects. Journal of Consumer Research 30: 292-304.

- Central News Agency (2014). Regain the confidence of food safety Wowprime Corporation set up the department of food and security. Retrieved October 21, 2014. Available online at: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/ch/news/2599063

- Chang, B.-H., & Chan-Olmsted, S.M. (2010). Success factors of cable network brand extension: Focusing on the parent network, composition, fit, consumer characteristics, and viewing habits. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 54(4): 641-656.

- Chang, J.W. (2002). Will a family brand Image be diluted by an unfavorable brand extension? A brand trial-based approach. Advances in Consumer Research 29: 299-304.

- Chiang, C.-F., Huang, Y.-M., & Huang, C.-T. (2017). Evaluating customer’s brand attitude toward hospitality brand extension. Journal of Global Management and Economics 13(1): 73-92.

- Chiang, C.F., & Jang, S.C. (2006). The effects of perceived price and brand image on value and purchase intention leisure travelers’ attitudes toward online hotel booking. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing 15(3): 49-69.

- Delgado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Aleman, J.L. (2001). Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing 35(11/12): 1238-1258.

- Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Aleman, J.L., & Yagüe-Guillén, M.J. (2003). Development and validation of a brand trust scale. International Journal of Market Research 45(1): 35-53.

- DeVellis, R. F. (1991). Scale development theory and applications. London: SAGE.

- Doney, P.M., & Cannon, J.P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 61(2): 35-51.

- Doyle, P. (1990). Building successful brand: The strategic options. Journal of Consumer Marketing 7(2): 5-20.

- Engel, J. E., Blackwell, R. D., & Miniard, P. W. (1993). Consumer behavior. Chicago: The Dryden Press.

- Farquhar, P., Herr, P.M., & Fazio, R.H. (1990). A relation model for category extensions of brands. Advances in Consumer Research 17(1): 856-860.

- Fazio, R. H. (1986). How do attitudes guide behavior? In R. M. & Sorrentino E. T. Higgins (Eds.), The handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (pp. 204-243). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18(3): 382-388.

- Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 58(2): 1-19.

- Ha, H. (2004). Factors influencing consumer perceptions of brand trust online. Journal of Product & Brand Management 13(5): 329-342.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hardesty, D.M., Carlson, J.P., & Bearden, W. (2002). Brand familiarity and invoice price effects on consumer evaluations: The moderating role of skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising 30(2): 1-15.

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hiscock, J. (2001). Most trusted brands. Marketing 1: 32-33.

- Ho, Y.-C., Su, Z.-S., & Chang, Y.-F. (2004). The effects of customers’ experiences and information processing on the buying intentions of extended brands. Marketing Review 1(1): 1-20.

- Howard, J. A. (1994). Consumer behavior: application of theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Huang, G. (2016). Moderating role of brand familiarity in cross-media effects: An information processing perspective. Journal of Promotion Management 22(5): 665-683.

- Huang, J.-S., & Zhou, L. (2016). Negative effects of brand familiarity and brand relevance on effectiveness of viral advertisements. Social Behavior & Personality 44(7): 1151-1162.

- Hyun, S.S. (2009). Creating a model of customer equity for chain restaurant brand formation. International Journal of Hospitality Management 28(4): 529-539.

- Iyer, S.G., Banerjee, B., & Garber, L.L. (2011). Determinants of consumer attitudes toward brand extensions: An experimental study. International Journal of Management 28(3): 809-823.

- Jin, N.P., Nathaniel, D.L., & Merkebu, J. (2016). The impact of brand prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 25: 523-546.

- Kang, J., Manthiou, A., Sumarjan, N., & Tang, L.R. (2017). An investigation of brand experience on brand attachment, knowledge, and trust in the lodging industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 26(1): 1-22.

- Keller, K.L., & Aaker, D.A. (1992). The effects of sequential introduction of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing Research 29(1): 35-50.

- Kim, H.-B., & Kim, W. G. (2005). The relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance in luxury hotels and chain restaurants. Tourism Management 26: 549-560.

- Kim, W. G., & Kim, H.-B. (2004). Measuring customer-based restaurant brand equity. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 45(2): 115-131.

- Kim, W.G., Jin-Sun, B., & Kim, H.J. (2008). Multidimensional customer-based brand equity and its consequences in midpriced hotels. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 32(2): 235-254.

- Kwun, D.J.W., & Oh, H. (2007). Consumers’ evaluation of brand portfolios. International Journal of Hospitality Management 26(1): 81-97.

- Kwun, D.J. (2010). How extended hotel brands affect the Lodging Portfolio. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property 9(3): 179-191.

- Lee, Y.-H., & Jhu, J.-H. (2013). The effect of extension methods on a typical brand extension evaluation and parent brand feedback. Fu Jen Management Review 20(2): 27-50.

- Li, C.Y., & Wang, Y.H. (2018). Love me, love my dog? The influence of brand attachment on brand extension evaluation. Sun Yat-Sen Management Review 26(2): 173-209.

- Lin, C.-H. (2006). The influence of brand extension of sports goods on consumers’ brand image perception and purchase intention. Journal of Physical Education and Sports 17(3): 1-16.

- Loken, B., & Roedder, J.D. (1993). Diluting brand beliefs: when do brand extension have a negative impact. Journal of Marketing 57: 71-84.

- Mabkhot, H.A., Shaari, H., & Salleh, S.M. (2017). The influence of brand image and brand personality on brand loyalty, mediating by brand trust: An empirical study. Jurnal Pengurusan 50: 71-82.

- Milberg, S.J., Goodstein, R.C., Sinn, F., Cuneo, A., & Epstein, L.D. (2013). Call back the jury: Reinvestigating the effects of fit and parent brand quality in determining brand extension success. Journal of Marketing Management 29(3-4): 374-390.

- Mollahosseini, A., Kermani, Z.Z., & Abassi, A. (2011). Identification and investigation of effective factors on consumer’s primary attitudes formation towards brand extension of Pegah company of Kerman. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research 5(2): 71-80.

- Morrin, M. (1999). The impact of brand extension on parent brand memory structures and retrieval processes. Journal of Marketing Research 36: 517-525.

- Nunnally, J.C., (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Perreault, Jr., W.D., & McCarthy, E.J. (2002). Basic marketing: A global managerial approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Pina, M., Iversen, N.M., & Martinez, E. (2010). Feedback effects of brand extensions on the brand image of global brands: a comparison between Spain and Norway. Journal of Marketing Management 26(9-10): 943-966.

- Regent Hotels Group (2018). Available online at: https://www.regenthotelsgroup.com/about-us

- Ries, A.L., & Trout, J. (1986). Positioning: The battle for your mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Roscoe, J.T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral science, international series in decision process (2nd Ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.

- Ryu, K., Han, H., & Kim, T. (2008). The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management 27(3): 459-469.

- Shin Yeh Restaurants (2018). http://www.shinyeh.com.tw/content/EN/about.aspx Song, Y., Hur, W.-M., & Kim, M. (2012). Brand trust and affect in the luxury brand-customer relationship. Social Behavior and Personality 40(2): 331-338.

- Starwood Hotels and Resorts (2018). Starwood preferred guest. Available online at: https://www.starwoodhotels.com/preferredguest/about/index.html

- Styles, C., & Ambler, T. (1995). Brand management. In S. Crainer (Ed.), Financial times handbook of management (pp. 581-593). London: Pitman.

- Sujan, M., & Bettman, J. R. (1989). The effects of brand positioning strategies on consumer’s brand and category perceptions: Some insights from schema research. Journal of Marketing Research 26: 454-467.

- Tauber, E.M. (1981). Brand franchise extension: New product benefits from existing brand names. Business Horizons 24: 36-41.

- Tauber, E.M. (1988). Brand leverage: Strategy for growth in a cost-control world. Journal of Advertising Research 28: 26-30.

- Ting, J.-H., & Lo, C.M. (2006). The exploration of the key successful factors of brand extensions. Journal of Global Management and Economics 2(1): 69-85.

- Tripodking Inc. (2018). Available online at: https://www.tripodking.com.tw/brand.php

- Tsai, S.P. (2005). Utility, cultural symbolism and emotion: A comprehensive model of brand purchase value. International Journal of Research in Marketing 22(3): 277-291.

- Tsai, Y.-S., Lu, W.-C., & Lin, S.-C. (2010). The development of a scale for measuring dilution effects of brand extension. Journal of National Taipei University of Technology 43(1): 1-19.

- Tseng, C.-H., & Wang, Y.-P. (2006). Does brand trust influence brand extension? An empirical evidence in Taiwan. Pan-Pacific Management Review 9(1): 1-23.

- Wang, Y.-Y., Chen,,S.-C., Lu, W-C., & Ho, W.-C. (2019). A study on the correlation between light food restaurant experience marketing, brand trust and brand value. Journal of Management Practices and Principles 13(2): 23-39.

- Wowprime Corporation (2018). Available online at: https://www.wowprime.com/investor/en/stores.aspx