Research Article

IS ELEPHANT WATCHING HELPFUL FOR MITIGATING HUMAN ELEPHANT CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA

2768

Views & Citations1768

Likes & Shares

The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus maximus) in Sri Lanka is the most prominent symbol of conservation as a ‘true flagship species’ (Desai, 1998). Attempts to ensure its continued survival in the wild is supported by a majority of Sri Lankans who consider it to be a valued resource (Bandara & Tisdell, 2003a, & b). But the Human-elephant conflict (HEC) is one of the biggest environmental and socio-economic crises of rural Sri Lanka. The intensification of HEC in recent times has been due primarily to the cumulative impact of the increase in human population, especially around the forest fringes, and the concomitant loss and fragmentation of habitats of Asian elephants (Santiapillai et al., 2010). The establishment of human settlements in wildlife habitats or corridors (i.e., elephant migration routes) is one of the major causes of HEC. The corridors are the connecting paths of protected areas in which preferable habitats, mainly water and food sources, are available.

Keywords: Education, Awareness, Contribution to mitigation measures through paying a conservation tax

INTRODUCTION

Although more than LKR 800 million is allocated for elephant conservation and compensation and for implementing HEC mitigation measures by the DWC, these outlays in expenditures have not succeeded in mitigating HEC. Due to budgetary constraints, the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) finds itself unable to spend more funds to implement mitigation measures in order to solve HEC. In the meantime, wildlife and nature lovers who visit national parks for ‘elephant watching’ express their concern, over the death of elephants due to HEC, arising partly out of an altruistic desire to prevent their extinction and partly out of a desire to observe these majestic animals in the wild during visits to national parks (DWC, 2003).

The present paper investigates whether visitors to these national parks are willing to ‘pay a tax’ for elephant conservation (which is called ‘conservation tax’) or for mitigating HEC in addition to their entrance fee. We argue that the revenue earned through taxing could be used by the Government of Sri Lanka to implement HEC mitigation measures. With this in mind, the main objective of the present study is to estimate the visitors’ willingness to pay a conservation tax which could then be used to implement strategies for the purpose of mitigating HEC in Sri Lanka.

STUDY SITES

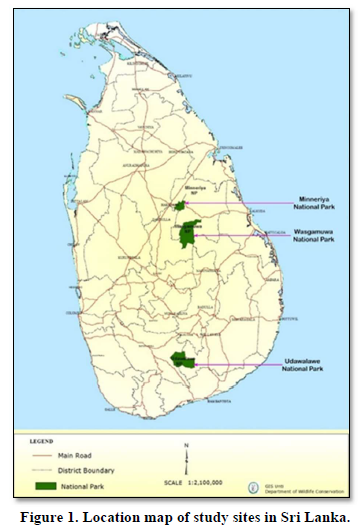

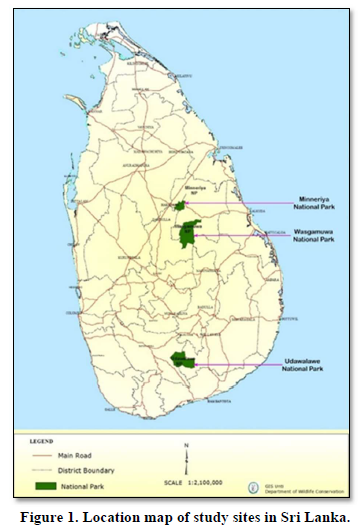

The study was carried out in three national parks, namely, MNP (249km2), UNP (308.21 km2) and WNP (395.85 km2), in Sri Lanka, which is an island located in the Indian Ocean (Figure 1). The tropical, dry, mixed, Semi Evergreen Forest predominating in all three sites offers a prime habitat for large mammals including Asian elephant. The main tourist activities in the three parks are wildlife safari, camping and overnight stays at the bungalows within the parks. In 2018, the MNP, UNP and WNP attracted 196,103, 330,381 and 31,609 visitors, respectively, where the majority of the visitors came to enjoy ‘elephant watching’.

METHOD

In the present study, the visitor demand for HEC mitigation strategies as the visitors’ willingness to pay a conservation tax at park level was estimated which could be used for implementing HEC mitigation measures to conserve elephants in the wild. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) was conducted at three national parks presenting different options for mitigating HEC.

Following Bateman et al., 2002, Hanley, 2002, Wright & Koop, 2002 the attributes and their levels found in DCE were defined and finalized based on a thorough discussion with local villagers around the three national parks and consultation with local experts. This method assumed that choices with regard to the mitigation of HEC can be described using a set of mitigation attributes such as ‘Implementation of short-term, medium term and long-term HEC mitigation measures’, ‘Education and awareness’, and ‘Contribution to mitigation measures through paying a conservation tax’.

RESULTS

The marginal WTP values were estimated using the resulted co-efficient values in the multinomial regression analysis (Table 1).

The highest MWTP values, ranging from LKR 21.27 to LKR 37.90, were recorded for the options, in terms of levels, under the attribute ‘Implementation of long-term mitigation measures. Under this attribute, visitors are willing to pay more, ranging from LKR 32.09 to LKR 37.90, for the option ‘Establishment and maintenance of park boundary electric fences’. The results of the study also show that visitors are willing to pay more for a proper compensation package for crop losses, property damages, attacks on humans, and human deaths at UNP and MNP, the amount being LKR 21.56 and LKR 38.17, respectively. But visitors to WNP are willing to pay more for the option ‘Each household is given thunder flares to safeguard themselves’ under the above attribute. Under the attribute called ‘Education and extension programs for HEC’, the visitors are willing to pay more, ranging from LKR 6.77 to LKR 31.68, for the combined options of ‘Awareness programs on HEC’ and ‘Awareness programs on household level mitigation measures for HEC’. If the total of highest MWTP values resulting from each preferred attribute is considered as a conservation tax for mitigating HEC, the conservation tax will be LKR 112.11, LKR 85.38 and LKR 95.37 at MNP, UNP and WNP, respectively.

CONCLUSION

This study reveals results from the application of a choice experiment to assess national park visitors’ preferences and willingness to pay a conservation tax for different strategies for mitigating HEC in Sri Lanka. The results show that a significant portion of respondents was willing to pay for the proposed HEC mitigation measures in order to conserve wild elephants. A majority of respondents were willing to pay more for the implementation of the long-term mitigation measures status-quo alternative which means visitors believe that there should be a long-term solution for mitigating HEC. The overall average MWTP as a conservation tax was LKR 98.76 per person per visit while the existing park entrance fee to a national park is LKR 60.00 per person excluding taxes. The resultant economic values thus constitute useful and reliable information for policy makers to make policy decisions regarding the levying of a conservation tax on visitors to national parks for mitigating HEC. The annual total number of visitors to MNP, UNP and WNP was 558,093 and, hence, if LKR 98.76 is charged as the conservation tax, LKR 58.12 million could be generated for elephant conservation. The total annual allocation by the Government for mitigating HEC is less than LKR 500 million at present. Therefore, from these three parks alone, 11% of the total expenses can be recovered. Accordingly, if this type of conservation tax is charged at other national parks, the Department of Wildlife Conservation will easily be able to generate the required allocation for mitigating HEC. In addition, public perception of elephant conservation, as evident from the survey, would be of value in generating more awareness in society regarding the importance of elephant conservation.

- Bandara, R., & Tisdell, C. (2003). Comparison of rural and urban attitudes to the conservation of Asian elephants in Sri Lanka empirical evidence. Biological Conservation 110: 327-342.

- Bandara, R., & Tisdell, C. (2003). Use and Non-use Values of Wild Asian Elephants A Total Economic Valuation Approach. Sri Lanka Economic Journal 4(2): 3-30.

- Department of Wildlife Conservation DWC (2003). Unpublished Report of Visitor Survey of National Parks in Sri Lanka Department of Wildlife Conservation.

- Department of Wildlife Conservation DWC. (2019). Unpublished Annual Reports of Department of Wildlife Conservation. Battaramulla Sri Lanka Department of Wildlife Conservation.

- Desai, A. A. (1998). Conservation of Elephants and Human-Elephant Conflict in Sri Lanka. Unpublished Technical Report. Department of Wildlife Conservation, Colombo Sri Lanka.

- Do, T.N., & Bennet, J. (2009). Estimating wetland biodiversity values a choice modeling application in Vietnams Mekong River Delta. Environment and Development Economics 14(2): 163-186.

- Hanley, N., Wright, R.E., & Koop, G. (2002). Modelling recreation demand using choice experiments: rock climbing in Scotland. Environmental and Resource Economics 22: 449-466.

- Santiapillai, C., Wijeyamohan, S., Bandara, G., Athurupana, R., Dissanayake, N., et.al. (2010). An assessment of the human elephant conflict in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Journal of Science 39(1): 21-33.