INTRODUCTION

Today, with the bitter division of the nation-state in many of the third-world countries and lacking the basic facilities of citizenship, the issue of immigration, asylum, and in its new meaning, "diaspora," has entered a new stage. The migration of people and elite people to developed countries has become more than ever. Therefore, the diaspora has caused conflicts in the discourse of national identity and nationalism. Therefore, the creation and expansion of the nationalism of Middle Eastern societies in Western societies and sending new ideas to the motherland is of great importance in sociology. Nationalism is theorized in the diaspora and practiced in the homeland. Therefore, diaspora communities significantly impact discourse, territorial politics, and conflicts. Nationalism occurs in the diaspora, and the diaspora communities significantly impact the discourse and territorial policies (Dianat, 2018, p. 54). On the other hand, one field that has faced the issue of diaspora for some time now is the field of sports, where many athletes migrate to other countries every year and acquire the citizenship of the destination country.

The Islamic Republic of Iran is one of the countries that have continuously faced the phenomenon of brain drain (elite athletes). According to the statistics provided by the United Nations, among 72 developing countries in the world, Iran ranks third in brain drain according to its population (5). On the other hand, according to the latest International Organization for Migration, Iran ranked 69th among 188 other countries with a rate of 3.4% of immigration.

Among the media's interpretation of this phenomenon as the "escape of athletes," the formation of the Olympic refugee team for the first time in the 2016 Rio Olympic Games and the presence of ten athletes from the countries of South Sudan, Congo, Ethiopia, and Syria in the three disciplines of judo, swimming and athletics in these games, and two Iranian and Syrian athletes in the 2016 Rio Paralympic Games caused the international sports literature to encounter a new phenomenon called "refugee sports".

Nevertheless, the immigration of athletes is an important issue due to the cultural and social impact of the issue, the media streams and public opinion addressing it, and the acceptance of foreign citizenship. The emigration of Iranian athletes in the last two decades has been different according to field and gender. According to the research findings, the most emigrated athletes belong to judo, with seven athletes; Taekwondo and rowing, with five athletes; and gymnastics and chess, with four athletes. We have seen the migration of athletes in wrestling, archery, lifeguard, veterans and disabled, football, karate, fencing, boxing, and handball. On the other hand, during the last year, the process of these migrations has increased so that about five national chess players have either migrated or resigned from the national team, and the last national athlete to migrate is also an Olympic medalist. Iran is in Taekwondo. The critical point is that the migrations in sports fields are primarily individual, and almost all are Olympic.

In Iran's sports arena, the asylum of two prominent athletes, Kimia Alizadeh, a taekwondo player who won a bronze medal at the Rio Olympics, and Saeed Moulaei, who won the first judo medal under the flag of Mongolia at the Tokyo Olympic Games. This news caused much speculation among the people of Iran to point the arrow toward Sports and political officials of the country, the politicization of sports, and the issue of political power and corruption. These reactions took on a new face in the virtual space because, with the emergence of new media, the possibility of communication conversations in the virtual space platform has increased. The platform allows users to create an online diasporic community and allow them to comment on It gives political phenomena such as the diaspora of athletes. Especially in more restricted countries like Iran, where mass media play a one-way role, users can exchange opinions and conflict opinions in the social media space, especially Twitter (which is limited in Iran).

In open democracies, social media are a supplement to offline demonstrations and an addition to the existing communication channels in which citizens can freely express their ideas (Zeng, 2020). On the contrary, street protests are not allowed in a restrictive society like Iran, and the media are systematically censured and monitored. In this context, social media, e.g., twitter, plays a more critical role as the citizens' only chance to engage in politics beyond severe restrictions, which are applied to traditional venues such as newspapers and TV (Sohrabi, 2021). In other words, social media is a choice for Western people to engage in politics, but they are a must for Iranians who want to play a role in the country's political sphere. Here, there is a high chance that the real struggles over political happenings with all sides involved occur on Twitter rather than other conduits; this is not necessarily true for Western democracies (Kermani & Tafreshi, 2022).

Therefore, the issue of this research is to analyze the tweets of Iranian users of the Twitter network about athletes (Alizadeh & Moulaei) who have acquired citizenship of another country to analyze the themes in Twitter and examine their discursive arrangements to respond to this political-sports reality. Also, this research aims to identify the involved and conflicting discourses in the Diaspora of Iranian athletes to draw essential signifiers in the occurrence of this phenomenon from the users' point of view, in addition to drawing its discursive order. This research is innovative because it is original in Iran's sports and media field. Since the Iranian diaspora has entered new dimensions and many athletes have emigrated, it is necessary to deal with people's reactions in the virtual space. Understanding their verbal discourse in criticizing the dominant discourse is essential.

Background

Diaspora as aesthetic formation: community sports events and the making of a Somali diaspora" is a research title by (Ramon Spaaij & Jora Broerse, 2018). The paper discusses how articulations of Somali diasporic become tangible and embodied in subjects who participate in this event. The authors conclude that these materialization practices can simultaneously elicit multiple forms and levels of belonging that foster a sense of integration and belonging to the nation.

Stuart Whigham, 2015 wrote an article on "Internal migration, sport and the Scottish diaspora in England." His paper aims to contribute to understanding this relationship by reflecting upon the role sport plays for members of the Scottish diaspora living in England. In particular, the discussion attempts to draw attention to the central role sport plays for these individuals to maintain a cultural attachment to their Scottish birthplace. Comparisons are also drawn with studies of the Scottish diaspora in more distant geographic contexts, as well as similar diasporic groups in the English context, such as the Irish diaspora.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Diaspora

There have been various interpretations of the concept of diaspora. In each of them, a part of the components of diasporic societies has been highlighted. However, it is necessary to look at the concept of diaspora and its different perceptions. The turn to the diaspora in the 1990s increased theoretical breadth and depth (Clifford, 1997). According to Carrington (2010), "Diaspora" is possibly the main idea in contemporary social hypothesis and a blossoming area of concentration across different disciplines.

Nevertheless, it is habitually and shockingly overlooked in sports studies and the sociology of games. Also, according to Brubaker (2005: 2), "most early discussions of the diaspora were firmly rooted in a conceptual 'homeland.'" Diaspora is a crucial heuristic for thinking about cultural heritage. While Diasporas are often constructed as homeless and displaced, they also draw on modes of cultural production, such as sport, to feel at home or emplaced (Joseph, 2014).

On the other hand, diaspora is a multivalent idea with changing definitions given individual chronicles, disciplinary assumptions, and the political directions of its defenders. It concurred that the term diaspora is from a Greek word meaning the dispersing of seeds and alludes to the formation of deterritorialized countries, or at least, "an association between groups across various country expresses whose shared characteristic gets from an original but perhaps eliminated country" (Anthias, 1998, pp. 559-560). Diaspora alludes to a condition of (poly-) cognizance and multilocality (Agnew, 2005), of being situated "here" in the spot of home and "there" in the country or some other spot scattered people groups have settled. Gilroy, (1993) and Hall, (1990) have been vital contributors in moving away from an essentialized understanding of diaspora to developing diaspora as a concept. For Hall (1990: 235, italics original), diaspora is defined "not by essence or purity, but by the recognition of a necessary heterogeneity and diversity; by a conception of 'identity' which lives with and through, not despite, difference; by hybridity".

However, the classical theory associated with Diasporas whose dispersal from their homeland and exile among various nations was caused by trauma, referred to a population. The population sustains a collective identity and solidarity preserved through a historical memory, a vision, or a myth regarding the homeland, often combined with a longing to return to it. This sense of belonging to an ideal homeland includes a commitment to maintaining or restoring the homeland and to its well-being and prosperity (Safran, 1991; Tölölyan, 1996; Sheffer, 2006).

Diasporas are formed through cultural forms such as music, fashion, literature, visual art, film, and sport, which cross borders or travel various "routes" and can unite dispersed people (Clifford, 1997; Gilroy, 1993; Hall, 1994). At the end of this section, it should be mentioned that according to Joseph, (2014). "While Diasporas are often constructed as homeless and displaced, they also draw on modes of cultural production, such as sport, to feel at home or emplaced." Despite definitions of diaspora, conceptually and theoretically, the definition forms our work is based on being separated from the homeland.

The Iranian diaspora and sports

In the history of Iran, we have seen five waves of immigration before the establishment of the Islamic Republic of (Iran &1979). Revolution (Neuvve-Eglise, 2007& Adelkhah, 2003) and three waves after that (Falahi & & Monavarian, 2008). The complexities of immigration and the existence of different criteria and indicators to define it have made it difficult to access accurate statistics. In contrast, Iranian immigration, including due to its politicization, has become more complicated, which has made it more difficult to access reliable statistics. However, the evidence clearly shows an increase in the tendency to migrate in recent years, especially among young people, due to the lack of economic, political, cultural, and social infrastructure. Furthermore, up until the early 1990s, the original Iranians in exile, the people who had seen the disturbance and experienced horrible loss, made up for their yearning for the nation of origin «as they had known it» by nostalgically recreating their thought process of as «authentic» Iranian culture (Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2015). Over 35 years after the Iranian revolution, which denoted the start of the proceeding with history of Iranian immigration, the diaspora has turned into a critical term for composing or portraying this continuous history, «what Iranians experience because of having left Iran» (Elahi/Karim 2011, p.382).

While talking about the rise of an Iranian diaspora, this implies, most importantly, that such perspectives have become «reconciled» and interweaving. Thus, the subsequent identification of an Iranian diaspora is over a simple proliferation of the «authentic» Iranian personality and culture of the nation of origin. It remembers the impacts and encounters of life in the «new home country» - including those feeling not at ease, evacuated, and minimized - and fashions them into another wellspring of character. In this, Iran, the old home nation, stays a significant guide, working not just as an «intermediary» that shapes this «reconciliation» but, considerably more critically, advises the condition regarding Iranians abroad. Many struggles described the setting wherein the Iranian diaspora appeared - one might call it a diaspora created by struggle - which implies it accompanies significant verifiable stuff. Scholarly as well as famous discussions about the Iranian diaspora are overwhelmed by the view that «Iranians abroad» comprise only a lot of philosophically divided, contending, and generally detached gatherings, particularly with regards to their relations to and political mentalities towards the nation of origin (Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2015). According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) statistics, immigrants with high skills and unique expertise make up the most significant percentage (35%) of the world's immigrants. According to the latest statistics published in 2015, Iran was ranked 69th among 188 other countries and had a rate of 3.4% in immigration. Also, the net migration rate of our country from 2015 to 2020 has a negative growth of 0.4 (IOM.int).

In Iranian sports, many factors have caused discouragement and migration of athletes. These issues include financial issues, lack of meritocracy, staying behind the line, problems in international laws and international federations, social freedoms, immigration laws of immigrant-receiving countries, federations' neglect of the conditions of their athletes, the existence of non-sports managers, the indifference of officials, the inefficiency of managers and lack of spiritual support. With the increase of globalization and professionalization between sports fields, athletes increasingly migrate to find work. This way, their sports, non-sports growth, and progress are formed and marked in different countries.

As indicated by a new report by Iran's official news agency IRNA, 29 of the athletes who moved from Iran until May 2022 made sense of the justification behind their flight as "inconvenience with the federation, impediments to the improvement of expert physicality" and 23 of them proclaimed political and religious reasons. While eight athletes referenced individual and family reasons, six competitors offered no expression. This information is terrific; they show firsthand that the movement of competitors originates from the inside and outside elements of the country. Essentially, scholarly distributions in light of field concentration uncover that there are institutional, social, financial, political, and social purposes behind the migration of competitors.

Social networks and diaspora

Being digital has become a key feature of contemporary lives. The term 'digital diaspora' - also known as e-diaspora or virtual diaspora - captures the relationship between technology, digital connectivity, migration, and diaspora. Digital diaspora is organized on digital and social media platforms. They use the internet and social media platforms for information, networking, education, and organizing/mobilizing (Yu & Sun, 2019. Brinkerhoff, 2009). Tsagarousianou, (2004) believes that the media and new information and communication technologies are used by members of diasporic communities and allow them to create new spaces in which spaces, distant places, and different experiences of people are united. According to Moerbeek and Timmermans (2010: 1-4), with the help of virtual communication networks, diasporas easily find people with everyday needs and interests and find the possibility to discuss various and even sensitive issues with each other on the internet and at least find solutions.

Today, Diasporas are in trans-temporal and trans-spatial situations (Mitchell: 1997: 534). Internet and virtual space have created exceptional value for geographically dispersed people. The capabilities of the internet encourage people to create online communities, using which they change the distance between people and the time for their interactions (Mitra, 2005). These groups use the internet to maximize the benefits of an online community (Lee, 2012, p. 1). Online diasporic communities need to be examined in the context of the 'networked public sphere (Benkler, 2006) or the 'global network society (Castells, 2001). As the internet crosses borders, it allows people from different countries to be interconnected. In the 21st century, it plays a crucial role in the global public sphere by enhancing and strengthening the link among people sharing the exact ethnic origins or political convictions (Castells, 2001; Calhoun, 2004; Dahlberg, 2007). it can be said that with the help of new media, the diaspora has become vocal. Diaspora's voice means the possibility of being heard and reaching a public opinion. According to Mitra, it is even possible for the marginalized voices of Diasporas to be transformed into a discourse (Mitra, 2005). According to Lee, unlike traditional media, the internet allows users to more easily and quickly produce a discourse that may challenge hegemonic views (Lee, 2012). In this way, their influence continues until, according to Karim, through their discursive activity in virtual space, new images of their society and nation emerge) (Karim, 2003: 175).

In addition to the fact that virtual space and social media allow the emergence of diasporic communities in all parts of the world based on familiar concepts it also creates opportunities for conversations for people who have migrated and settled in the host country. Social networks allow talking about the diaspora phenomenon among users, creating a kind of digital public domain.

METHODOLOGY

In this research, the three-level model of Fairclough's discourse analysis and its integration with the thematic analysis method has been used to perform the analysis.

Fairclough (1989, 1992, 1995, 2001) described that a text is not a process but rather than is a product and is just a part of discourse - the whole process of social interaction. He developed a three-dimensional framework of CDA consisting of three stages: description, interpretation, and explanation. The first stage, description, "is concerned with formal properties of the text" (p. 26), where the text is the object of analysis, which generally deals with identifying and labeling specific formal properties or features of the language, such as vocabulary, grammar, and textual structures. The second stage, interpretation, "is concerned with the relationship between text and interaction" (p. 26). In this stage, the text is seen "as the product of a production process and as a resource in the process of interpretation," and analysis deals with the "cognitive processes of participants" (pp. 26-27). The third stage, explanation, "is concerned with the relationship between interaction and social context - with the social determination of the processes of production and interpretation, and their social effects" (p. 26).

In addition, another method of this research is thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is the process of identifying patterns or themes within qualitative data. Braun & Clarke (2006) suggest it is the first qualitative method to be learned as 'it provides core skills that will be useful for conducting many other kinds of analysis' (p.78). The goal of thematic analysis is to identify themes, i.e., patterns in the data that are important or interesting, and use these themes to address the research or say something about an issue. This is much more than simply summarizing the data; an excellent thematic analysis interprets and makes sense of it.

Regarding applying these two methods in this research, since thematic analysis remains mainly at the level of description and interpretation, CDA leads to a better explanation of the research problem. We have used the two levels of description and interpretation in Fairclough's approach with the method of thematic analysis and the explanatory level of Fairclough's CDA and social theories. Also, as Braun and Clarke stated, the thematic analysis provides a basis for other analyses, which in this research became the basis for analyzing the discourse of the research problem.

The credibility of interpretations made from discourse analysis approaches is enhanced when the researcher uses a common, shared set of rules, beliefs, or frame of reference to interpret the analyzed sign. The credibility of discourse analysis is also enhanced when the text's interpretation is critical-illuminating the role of language in maintaining and reproducing social, political, economic, and structural inequities and dominance concerning the actors involved (Jaipal & Jamani, 2014). It has been tried to use specific rules regarding data extraction to analyze Iran's sports diaspora and the research problem and use social actions to deconstruct the existing sub-discourses and the relationship between the actors.

Also, in this research, all the hashtags related to #Kimia_Alizadeh (#کیمیا-علیزاده) and #Saeed_Moulaei (#سعید-مولائی) were considered as a statistical population. Then the sample selection was made using the Purposeful theoretical sampling method with the maximum variation strategy.

RESULTS

Description and interpretation

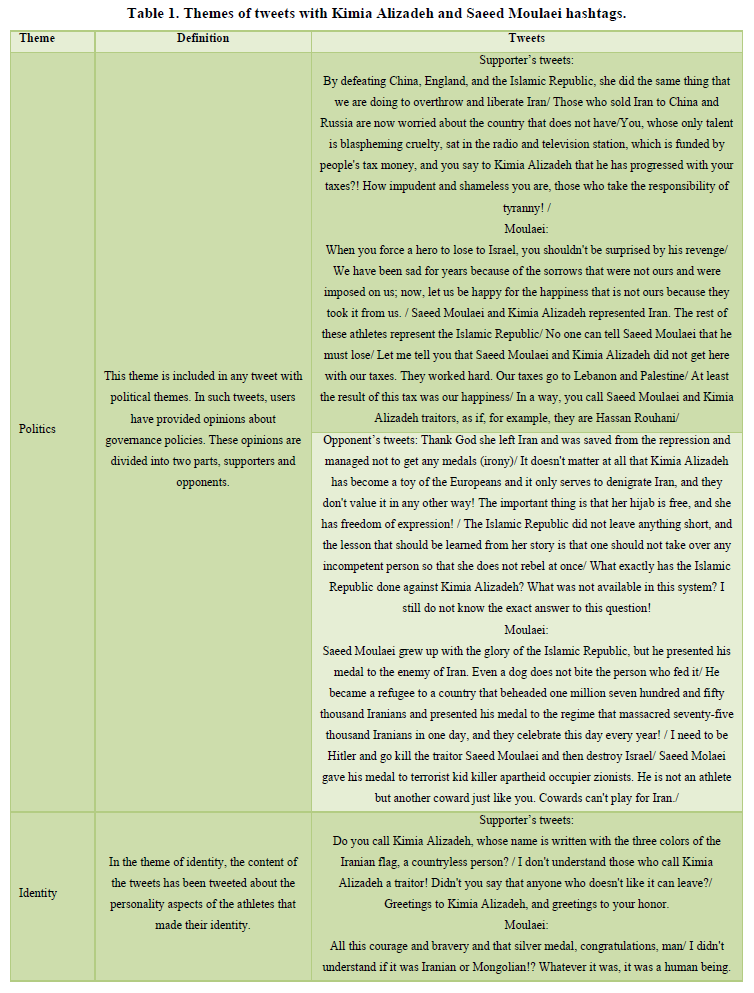

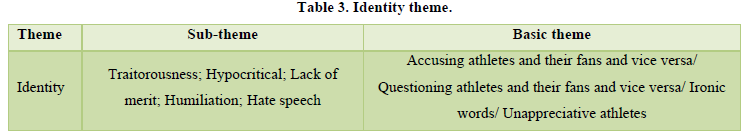

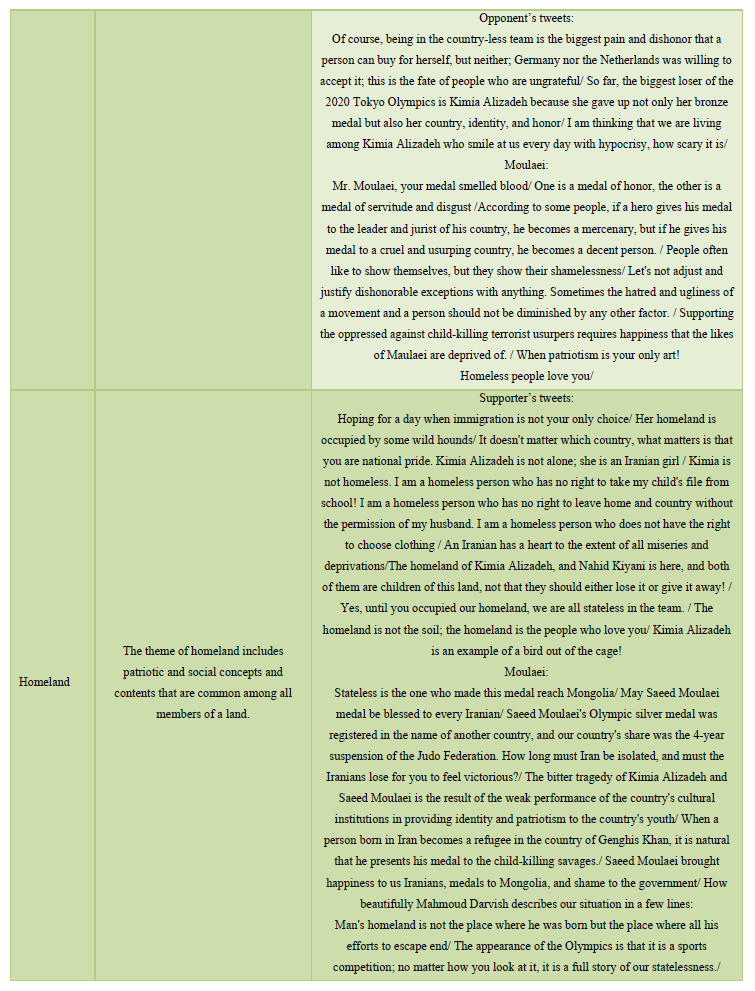

In this section, we try to describe and interpret the themes that users have raised in their tweets about the migration of athletes, which is as follows (Table 1).

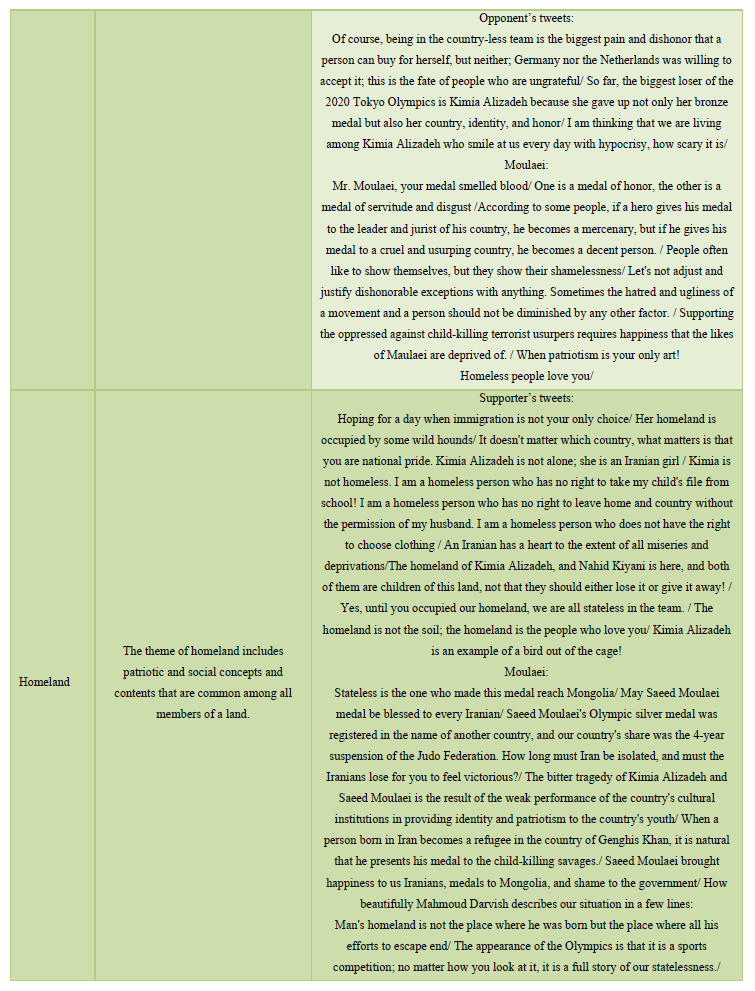

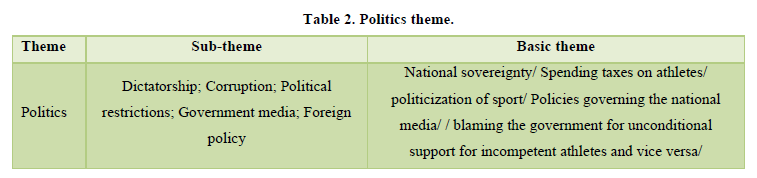

According to Table 2 number, referring to keywords such as dictatorship, corruption, political restrictions, state media, and foreign policies were the main themes of political tweets. Users are divided into two groups’ supporters and opponents. Supporters of athletes' migration consider political issues and ruling ideology as the cause of migration and support their decision. Opponents, on the other hand, point to the possibilities that the government has provided for the success of athletes and defend the ruling ideology.

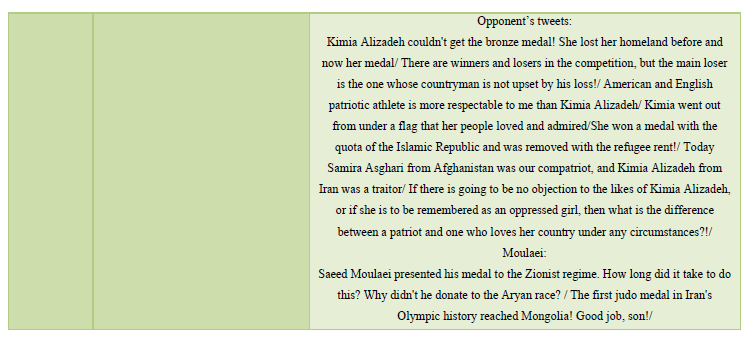

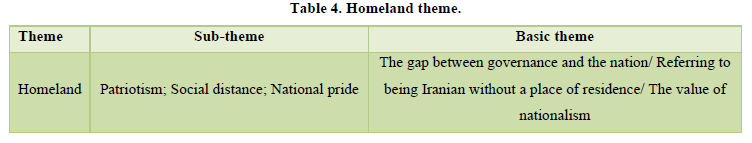

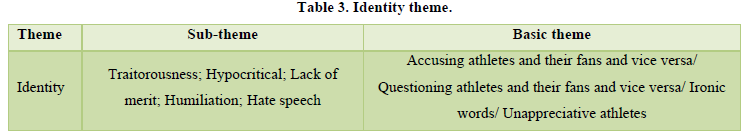

According to Table 3 number, these tweets' main themes are treachery, hypocrisy, inadequacy, humiliation, and hatred. Users have mentioned the personality and identity aspects of the athletes. Supporters of the athletes believe that this decision has nothing to do with their lack of honor because they still love their homeland and consider humanity a more important criterion for judging. However, on the other hand, the opponents question the identity of these people, calling them ungrateful people. They know their country. They humiliate the sports and personal identity of the athletes, and they consider this a danger to the future of sports. In this context, encouragement and congratulations from the fans can also be seen. In these tweets, athletes have been considered as a person whose personality traits are the main topic of the tweet, regardless of other political and social contexts.

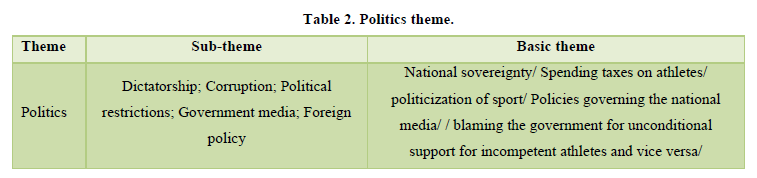

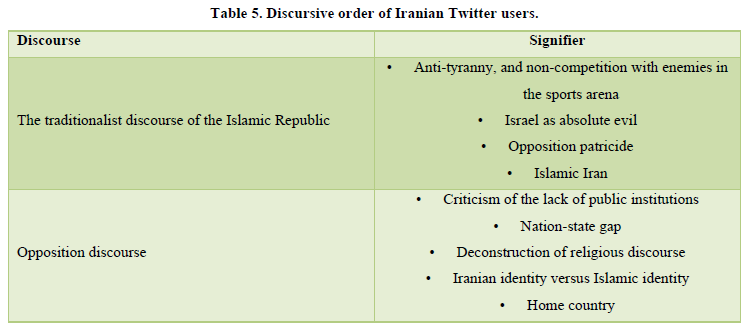

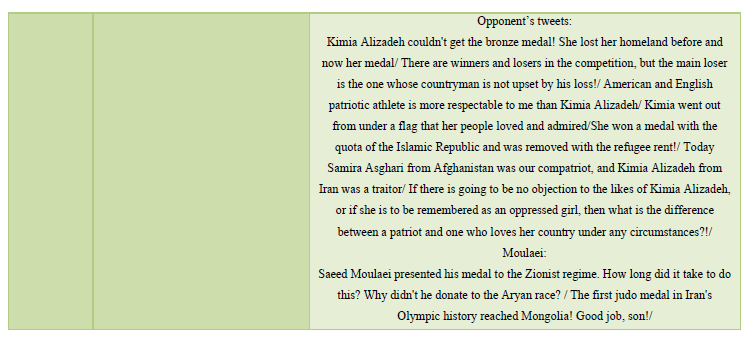

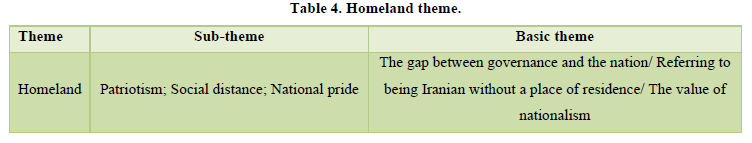

According to Table 4 number, patriotism, social distance, and national pride are the main themes of tweets. Athletes are not considered individuals, but their collective and national identity is the central theme. Supporters point to the gap between the government and the nation and consider the Iranian identity distinct from the ruling system. The users do not consider the land as a physical category but rather as a deep feeling within the human being; that is why the fact that the athletes are Iranian is enough to make them feel national pride. On the other hand, the opponents see the value of nationalism in enduring hardships and appreciating minimum facilities and consider such migrations to be the cause of social disruption and the collapse of collective and national identity. They are called stateless who have turned their backs on their race and country and cooperate with their enemies.

EXPLANATION

In Fairclough's model, interpretation deals with the relationship between meanings and discourse contexts. This model attributes the explanation of meanings to social, cultural, and political contexts. It also provides a possibility to understand the text in the light of the objective context and, at the same time, rethink the objective context in the light of the text.

Studies show that ideologies often have a polarized structure and reflect the competition or conflict of group members and are the factor of classification into two categories: in-group and out-group (Van Dijk, 2005). The analysis of these tweets indicates the existence of such biases. Under the identity discourse of the Islamic Republic of Iran, people in the group are considered to compete only under the banner of the Islamic Republic of Iran; otherwise, they are addressed with nicknames such as patriot, traitor, dishonorable and ignorant. In these tweets, we see that people who have a discourse approach in line with the dominant discourse of the Islamic Republic are trying to challenge the performance of Kimia Alizadeh and Saeed Moulaei, because they believe that leaving the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran is nothing but a failure. According to Van Dijk, (2005) this explains why many ideological mental infrastructures or ideological functions are polarized based on in-group and out-group differences, especially generally between "us" and "them".

On the one hand, we are witnessing the creation of two new sub-discourses under Iranian identity. First, the Iranian opponents of the country's current situation in society and the field of sports in particular (supporters of athletes' immigration) consider the historical approach to national identity. These people look at the issue of Iranian identity retrospectively because they believe that Iran's identity has been challenged due to the performance of the Islamic Republic. Second, these people consider the Iranian identity an exception after the revolution and its overlap with the discourse of the Islamic Republic and are supporters of the status quo and critics of the athletes' immigration. They find success meaningful in the shadow of the homeland and the Islamic Republic. Here we are witnessing the intersection of two topics and the macro discourse of politics and identity. The political dimension of sports and society and the issue of power have changed identity. In fact, according to Lacla and Mouffe, identity is considered here as an empty signifier to which different actors attribute their desired meaning.

The traditionalist discourse of the Islamic Republic

After the Islamic revolution's victory, the Islamic Revolution discourse was raised with the support of Imam Khomeini (RA) and the clergy. This discourse gradually established its signs and concepts in a discourse conflict and confrontation with other discourses. Concepts such as religious democracy, Islamic human rights, jurisprudence, ijtihad, and defense of the deprived and the oppressed, gradually became prominent in this discourse and formed its discourse manifestations. The principles of the Islamic Revolution of Iran are God-centeredness, the right of people to determine their destiny, intertwining of religion and politics, anti-tyranny, justice, spirituality, rationality, and universal audience (Jahanian and Shafazadeh, 1392: 113).

The discourse of the Islamic revolution shaping and placing the "Islamic government" or "religious democracy" in the form of the Islamic Republic has sought to give meaning to the fact that religion and politics and religion and the state are inextricably linked. From the point of view of religious experts, the particular essential task of the Islamic political system is to create a foundation for getting closer to God. All the decisions and programs in this system aim to realize this goal. Therefore, the discourse of the Islamic Republic is partly based on anti-tyranny and support for the Palestinian people and hostility to Israel; through the lens of this discourse, sports competition with Israeli athletes is prohibited. In the discourse of the Islamic Revolution, these losses are considered a victory in God's presence. Saeed Moulaei also decided to emigrate due to not fighting with Israel and presented it to Israel under the flag of Mongolia after winning the silver medal at the Tokyo Olympics. This caused adverse reactions in the eyes of supporters of the Islamic Revolution, who called him an animal and unworthy.

In any case, the dominant discourse is obviously trying to marginalize the alternative discourse. Here, the discourses try to highlight their strengths and superiority and the weaknesses of the opponent's discourse. On the other hand, they push their weaknesses and the opponent's strengths to the sidelines. The dominant discourse of the Islamic Republic (here, sports) tries to humiliate the opposition's discourse to honor the athletes' actions with the Islamic Republic's goals. It uses discursive measures such as sanctification, irony, labeling, insulting, and insignificance. It aims to destroy the opposition's discourse and the athlete's performance. Pay attention to this tweet:

Tweet 1: The fact that Saeed Moulaei presented his medal to Israel it is because he can kiss Israel's foot for any humiliation; maybe he can be saved from Mongolia, he can live somewhere else, and otherwise, the dog will not give his medal to Israel.

Tweet 2: What exact boundary has Imam Musa Sadr drawn with his words that Israel is absolute evil and if Israel and the devil fight together, we will stand by the devil #Saeed-Molaei.

Tweet 3: When a person born in Iran becomes a refugee in Genghis Khan's country, it is natural to present his medal to child-killing savages. #Saeed-Molaei.

Tweet 4: And the end of selling the homeland is nothing but bananas. #Kimiya Alizadeh.

Tweet 5: Thank God that Saeed Moulaei won a medal because by presenting it to Israel, he showed that he is an animal forever and ever #Kimiya Alizadeh.

These tweets with derogatory and insulting sentences show that the discourse of the Islamic Republic does not reflect any kind of going under the flag of another country to oppose the principle of sovereignty of the Islamic Republic. In fact, in their eyes, acting in line with Israel's goals is like the highest evil, and Saeed Moulaei is also a friend of absolute evil and darkness.

OPPOSITION DISCOURSE

In contrast to the discourse of the Islamic Republic of Iran, there is the discourse of the opposition, which has both domestic and foreign origins, but the majority of Iran's opposition, which is the reformist opposition, resides within the borders of Iran. The foundation of opposition thought is related to the possibility of redistribution of political power in society. A fundamental change in power relations and its distribution method can lead to the emergence of legal opposition. However, the way of perception and dealing or the political ideology of the political power holders has an important effect on the distribution of power resources, and the ideology of the rulers has an effect on the type of political system and the form of the opposition. The existence of a competitive political system requires the existence of a competitive ideology among the rulers, and an absolute ideology that considers power to be absolute, sacred, and pure obedience prevents the emergence of the living beings necessary for competition and political opposition. In fact, it is based on the discourse approach, where its relationship with the cultural and political functions of the society is considered. It is possible to consider two general interpretations regarding the problem of athletes' diaspora, namely, Kimia Alizadeh and Saeed Moulaei.

The reason for their opposition in cyberspace is based on the two main approaches of the Islamic Republic regarding their issue. First, in the case of Kimia Alizadeh, the limitations of women's sports (competition with hijab, etc.), the lack of structural equality with men's sports, and the limited infrastructure facilities for women's sports. In the case of Saeed Moulaei, the most important ideological factor that causes his migration is the influence of the dominant political ideas of the society on the sphere of sports, which has caused the sports activities of athletes to undergo negative and profound changes. Saeed Moulaei was the world's first-ranked player and world gold medalist, who lost to Kazakhstan's judoka in the fourth round of the Paris Grand Slam 2019, so he did not face the Zionist judoka in the semi-finals.

Since Iran's dominant ideology is absolutist and not competitive, political flexibility cannot be expected in various fields, including sports; for this reason, the intellectual claims of the dominant discourse dictate that the political and ideological goals of the country be implemented because if outside the scope of this discourse If an action is taken, the actors will be rejected. This is also about Saeed Moulaei and the dominant discourse's desire not to compete with the Israeli athlete, which caused him to lose to his Kazakh opponent. This happens while the lack of fighting and losing in the ethics of the athletes is contrary to their sports performance, and this can cause the formation of opposition among the victim athletes.

According to Fekri & Rahbar, (2022) credible opposition is the opposition that exists inside the country and is legal because the process of objectivity and existence is focused on the current programs and policies of the system and participates in the complex process of relations between the society and the government. In other words, this opposition deals with the issues in an objective and concrete manner. Some critics have a structural approach and not overthrowing the government.

In the view of such oppositions, there is a weakness of the public sphere and civil institutions, which creates the cause of such destructive activities as the sports diaspora. In fact, the attempt to suppress civil institutions and social movements takes the political and social breathing space from the sections of society that try to raise their legal and trade union demands through legal and legitimate channels and forces them to abandon their legal and social demands. And their trade unions, and due to the lack of opportunity for dissatisfaction in the form of reformist movements within the system, the possibility of structural disturbances increases. The same can be found in the etiology of the diaspora and the migration of athletes and actions contrary to the discourse of the Islamic Republic.

Tweet 6: The bitter tragedy of Kimia Alizadeh and Saeed Moulaei is the result of the weak performance of the country's cultural institutions in providing identity and patriotism to the country's youth #Saeed_Moulaei.

At the time of these sports deconstructions, the opposition sometimes considers the issue of Iranian identity:

Tweet 7: The most Iranian medal ever received.

By reading Saeed Moulaei's performance as an Iranian, users separate themselves from the identity of the Islamic Republic and equate actions that contradict the Islamic Republic's discourse with the Iranian identity. In fact, the duality of Iran/Islamic Republic or the people/Islamic Republic is formed, each of them trying to deconstruct the competing discourse in their total discourse. Because according to Iranian thinkers such as Bashirieh (2003), Iran's identity politics has a wide connection with the government and especially the ideology of the government or tweet.

Tweet 8: Again, Iran won over the Islamic Republic #Kimiya Alizadeh.

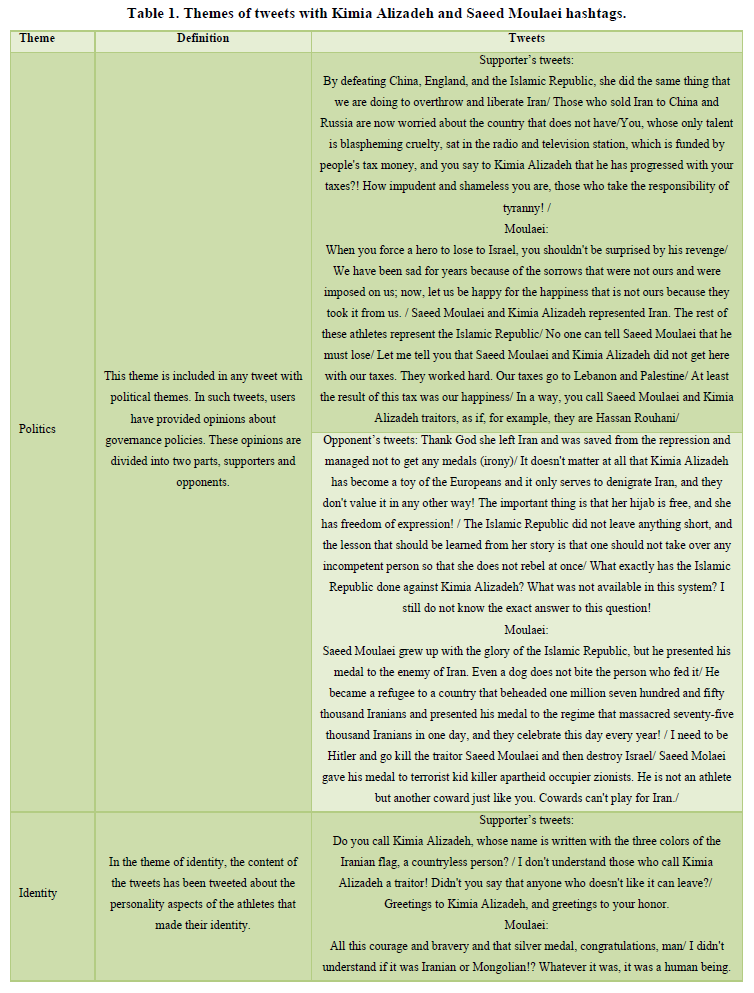

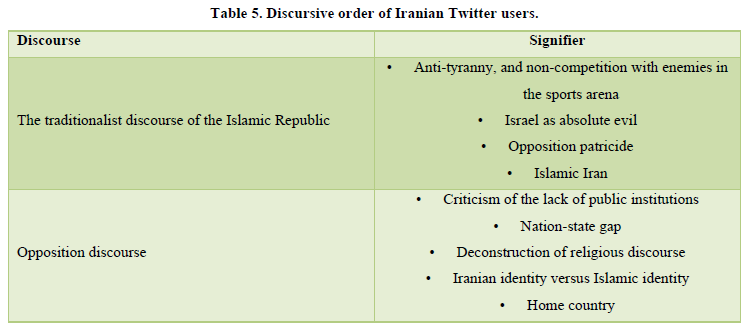

On the Twitter, which is interactive, there is a space for discussion; we are witnessing an atmosphere of hostility regarding the existing discourse competitions about the Iranian diaspora (Alizadeh & Moulaei), where each of the discourses tries to give meaning to the actions of the athletes and their identity under their own discourse. Fairclough understands the meaning of the atmosphere of conflict in the social structures of power relations. Therefore, Twitter users' interpretation of their intended meaning becomes important, and discourse order is also formed. However, according to the topics in Table 5, which mostly have a discourse approach, it is possible to identify the roots of the formation of the national opposition that supports the activities of athletes and the policies governing the sports environment that create the phenomenon of Iranian athletes' diaspora. However, according to the analyzed tweets and recognition of the discourses raised in the Twitter space, the discursive order of the research is as follows:

On the other hand, considering the discussed issues, apart from the discourse conflicts that have formed between the two traditionalist discourses of the Islamic Republic and the opposition, we are witnessing its continuation in the Twitter space regarding the issue of athletes' immigration. There are two issues regarding these two study cases that migrated and brought the Iranian sports diaspora into a new dimension:

Restrictions on women's sports: the general policy of the country regarding women's sports and the restrictions created for it, along with the general restrictions on Iran's sports, has created the causes of the Iranian diaspora, which we saw reflected in tweets.

Anti-sports macro policies: the impact of politics on sports and neglect of some Olympic sports, administrative corruption in the structure of society and existing institutions, and the lack of meritocracy in the management of large sports organizations, etc., have caused the creation of diaspora and the migration of athletes, which in tweets Its burden has been drawn through the lens of paying to the homeland and the administrative and political defects of that homeland.

Tweet 9: I wish the homeland was a place to stay #Kimiya Alizadeh.

Tweet 10: Hoping for a day when immigration is not your only choice #Kimiya Alizadeh.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This research was done to investigate the problem of Iran's sports diaspora and its reflection in people's thoughts and its expression on Twittersphere as a social media to answer the themes of the opponents and supporters of immigration regarding the Diaspora of Kimia Alizadeh and Saeed Moulaei. Moreover, finally, by using Fairclough's model at the level of explanation, let us find out what discourses are involved in these comments and draw the discursive order. This research shows that despite the Twitter filter in Iran, this social network has become a public domain for expressing opinions and discussions. As Castells (2001), Calhoun, (2004), and Dahlberg, (2007) have pointed out that social networks have formed links in various fields. A field where there are discourses and themes from different spectrums. In the subject examined in this article, on one side of the spectrum is the traditionalist discourse of the Islamic Republic and on the other is the opposition discourse. Common themes are used in both discourses. The meaning of each sub-theme varies depending on the desired discourse of the users. While the opposition discourse uses the sub-themes of ideology and political restrictions to support the immigration of athletes, the traditionalist discourse considers these two sub-themes in the direction of the principles of the Islamic revolution and the centrality of Islamic government and democracy. Tweets with the theme of identity, using irony, humiliation, tagging, and spreading hatred, in line with the two main discourses, have addressed the athletes' personality characteristics. In this context, traditionalist discourse has judged the character of Alizadeh and Moulaei and their supporters, and opposition discourse has questioned the character of the traditionalists. In this context, the primary audience of the opposition discourse is the supporters of the traditionalist discourse, while the primary audience of the traditionalist discourse is mainly two sports personalities. In both discourses, using this theme, regardless of political and social contexts, the users have targeted the personality and individual identity of the athletes. Another noteworthy point in the tweets analysis was the users' use of poetry to taunt and irony the rival's discourse. Another critical point in all three themes is that they share the sub-theme of treason in accusing the rival discourse. In the theme of homeland, users in both discourses had a completely different definition of homeland, originating from the different processes of socialization and worldview of people. Furthermore, it caused social distance within society; this social distance, to the point of creating a gap between the government and the nation, has progressed; What is defined as patriotism in the traditional discourse means patriotism in the opposition discourse and vice versa. In fact, as Tsagarousianou, (2004) says, social networks have created a space to create unity in groups supporting a particular discourse. The analysis of the themes and discourse of the diaspora issue on Persian Twitter showed that Dianat's (2018) ideas about the impact of the diaspora on the discourses about Iranian society apply. In such a way, discourses have moved towards hostility. According to Fairclough, (1989) such an atmosphere is derived from power relations. Such relations and structures in the issue of the Iranian sports diaspora have caused two competing discourses to have opposite and hostile definitions of typical verbal sub-themes. Also, the concept of gender was not the theme and sub-theme of the investigated tweets. Only one user mentioned the discrimination of news coverage of Alizadeh and Moulaei; in fact, the theme of the homeland and the sub-theme of nationalism were more important than the concepts of gender and race in both discourses.

On the other hand, identity, which forms the basis of the diaspora formation, has been split. A concept formulated under a homeland and land, but the meanings attributed to it are different, and it is considered an empty signifier. The opposition's discourse sees identity from a historical and retrospective perspective, sees Iran as opposed to and separate from the Islamic Republic, and negates this part of identity. In fact, in this discourse, Iran is like a people. Therefore, the formation of athletes' diaspora, in addition to having identity roots, also has structural roots. The poor performance of existing management institutions and the unification of politics and sports have led to the migration of athletes such as Alizadeh and Moulaei.

Adelkhah, F (2003). Partir sans quitter quitter sans partir Critique Internationale. Presses de sciences pp: 141-155.

Agnew, V. (2005). Diaspora Memory and Identity A Search for Home. Toronto University of Toronto Press.

Ananda, M. (2005). Creating immigrant identities in cybernetic space Examples from a non-resident Indian website. Media Culture and Society 27,371-390.

Anthias, F. (1998). Evaluating diaspora: Beyond ethnicity. Sociology 32,557-580

Bashirieh, H, (2003). Political ideology and social identity in Iran critic.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Brinkerhoff JM (2009) Digital Diasporas Identity and Transnational Engagement. Cambridge University Press.

Brubaker, R. (2005). The diaspora. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28,1-19.

Calhoun, C. (2004). Information technology and the international public sphere. In D. Schuler & P. Day Shaping the network Society The new role of civil society in cyberspace. Cambridge MIT Press.

Carrington, B. (2010). Race Sport and Politics the Sporting Black Diaspora. London Routledge.

Castells, Manuel. (2001). The Internet galaxy. Oxford Oxford University Press.

Clifford, J. (1997). Routes Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press.

Dahlberg, L. (2007). The Internet deliberative democracy and power radicalizing the public sphere. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 3, 47

Dianat, M. (2018). Kurdish Diaspora Elites Diaspora. State Studies, 4, 79-108.

ELAHI, B,Persis Karim (2011). Introduction Irianian diaspora. Comparative Studies of South Asia Africa and the Middle East 31, 381-387.

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and Power. New York Longman.

Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and Socil Change. Cambridge Polity Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis The critical study of language. London Longman.

Fairclough, N., Wodak, R., Meyer, M. (2001). Critical Discourse Analysis as a method in social scientific research. In. & Methods of critical discourse analysis. London Sage Publications.

Falahi, K. Monavarian, A. (2008). A Study on the Factors of Elits Human Capital Immigration and Suggesting Appropriates to Prevent this Phenomenon. Knowledge and Development 15, 103- 132.

Fekri, M., & Rahbar, A. (2022). Recognition of the confrontation between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the opposition, on the fortieth anniversary of the Islamic Revolution. Political Sociology of Iran, 5, 1-30.

Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge MA Harvard University Press.

Hall, S. (1994). Cultural identity and diaspora. In Williams P and Chrisman L Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory. New York Columbia University Press pp: 392-403

Hall, S. (1990). The emergence of cultural studies and the crisis of the humanities. October 53, 11-23.

Heinrich Böll Foundation, (2015). Publication series on democracy 40 identity and Exile the Iranian Diaspora between Solidarity and Difference Edited by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in cooperation with Transparency for Iran Idea and editing Resa Mohabbat Kar. Available online at: https://www.iom.int/countries/iran-islamic-republic.

Jaipal Jamani, K. (2014). Assessing the validity of discourse analysis: transdisciplinary convergence. Cultural Studies of Science Education. Cultural Studies of Science Education. 9, 1-7.

Joseph, J. (2014). Culture community consciousness The Caribbean sporting diaspora. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 49,669-687.

Karim, H. (2003). The Media of Diaspora. New York Routledge. Lee Eunkyung Digital diaspora on the web The formation and role of an online community of female Korean im migrants in the US for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication Information and Library Studies. Graduate School New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Mitchell, K. (1997). Different Diasporas and the hype of hybridity. Environment and Planning D Society and Space, 15, 533-553.

Moerbeek, Kimon & Timmermans, Nikki. (2010) Social media Empowering Migrant Communities. A written report on Panel Discussion. Amsterdam Kennisland. Available online at: http://www.lmi.ub.es/bridgeit/files/101101_Report_Migration_DP_BridgeIT.pdf

Neuve Eglise, A. (2007). La diaspora iranienne dans le monde un acteur transnational au centrale De flux et de jeux d influences multiples revue de Téhéran. 14.

Ratten, V. (2022). The role of the diaspora in international sports entrepreneurship. Thunderbird International Business Review, 64,235-249

Safran, W. (1991). Diasporas in modern societies Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora A Journal of Transnational Studies 1, 83-99.

Sheffer, G. (2006). Transnationalism and Ethnonational Diasporism. Diaspora 15, 121-145.

Spaaij, R, Broerse, J. (2018). Diaspora as aesthetic formation community sports events and the making of a Somali diaspora, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45, 752-769.

Tsagarousianou, R. (2004). Rethinking the concept of diaspora mobility connectivity, and communication in a globalized world. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 1, b52-b65.

Tölölyan, K. (1996). Rethinking Diaspora Stateless Power in the Transnational Moment. Diaspora 5, 3-36.

Van Dijk, T. (1998). Politics ideology and discourse. Elsevier Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Volume on Politics and Language pp: 799-870.

Whigham, S (2015). Internal migration sport and the Scottish diaspora in England Leisure Studies, 34. 438-456.

Yu, H., & Sun, W. (2019). Introduction social media and Chinese digital diaspora in Australia. Media International Australia, 173, 17-21.