2719

Views & Citations1719

Likes & Shares

Objective: To study the supply and needs of sexual and reproductive health (RH) services for women incarcerated at the Ouagadougou prison (MACO) in Burkina Faso.

Methodology: This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. The study population included female residents of MACO. Data were collected using a form containing the study variables and were subsequently analyzed on Epi-info.

Results: Fifty-four incarcerated women were included in the study. The mean age was 31.5 years. Forty-five women raised complaints pertaining to their sexual and reproductive health. The complaints were related to pelvic pains in 26 cases. The most common (60% of cases) gynecological pathology was a suspicion of mild and acute genital infections. All women were screened for cervical cancer with VIA/VIL; one positive case was recorded. The minimum package of activities offered by the MACO care unit is essentially curative. Routine RH prevention activities are not conducted in the MACO infirmary.

Conclusion: Our study observed that the incarcerated women did not have access to quality RH services compared to women in the outside world. These points need to be included in different RH programs organized in Burkina Faso.

Keywords: Female prisoners, Needs and supply of services, Sexual and reproductive health, Burkina Faso

Abbreviations: LPK: Precancerous Lesions; VIA: Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid; VILI: Visual Inspection with LuguolThe prison population is growing globally, and a major proportion of the inmates belong to the sexually active age group. More than 11 million people are imprisoned at any given time, and more than 30 million pass through the prison system annually [1]. In Burkina Faso, prisons and correctional facilities are overcrowded. Despite the theoretical national capacity being only 4,980 inmates, remand prisons in the country housed 6,368 inmates in the year 2017 [2]. In 2018, the Ouagadougou Prison and Correctional Centre (MACO) had 2364 detainees-or 30.3% of the country's 7812 detainees [3]. Furthermore, out of the total number of detainees at the national level, 249 were women (3.2%). Ghanaian prisons housed between 11,000 and 14,000 inmates, with women constituting about 2% of the prison population [4]. The proportion of women in prison is increasing rapidly. However, little is known about their health care needs [5]. Most prisoners in the sexually active age group demonstrate the importance of having reproductive health policies for prisons.

Studies in the United States have shown that incarcerated women have higher rates of unintended pregnancies and an unmet need for contraception compared to the general population. These studies further suggested that offering family planning services in correctional facilities can improve access to contraception [6]. One study by Clarke [7] also showed that women in prison are more likely to suffer from a variety of health problems, including sexually transmitted diseases; gynecological problems; mental health problems; kidney infections and chronic health problems such as hepatitis, HIV, hypertension, emphysema and asthma [7,8].

The WHO Kiev Declaration (2009) on Women's Health in Prison states that advice and methods of contraception should be made available to women in detention [9]. According to the WHO, women in prison are at a high risk of sexual and reproductive diseases, including cancer and sexually transmitted infections. This is in part due to the typical background of women in prison, which may include a history of drug use, sexual abuse, violence and engaging in sex work and unsafe sex practices [9]. Women who have been abused may, therefore, engage in high-risk sexual behaviors, thereby increasing their risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections.

Despite the WHO recommending the inclusion of screening programmes for reproductive diseases such as breast cancer in the standard operating procedure in women's prisons [9], reproductive health care is not systematically available in these settings. This is especially true in low-income countries such as Burkina Faso. Furthermore, women in prison do not receive the health care they need and have a lower utilization rate compared to other women [10]. Services that are available are inadequate and very limited to effectively meet women's health needs.

The 2009 WHO recommendation on women's health in prison has, unfortunately, not been followed by national and regional policies. Relatively few countries have instituted policies governing access to reproductive health care for women in prison, and, in case such policies exist, they vary widely [11].

The sexual and reproductive health of prisoners is an important public health issue because there are interactions between prisons and society [11]. The increase in the number of women in prison makes the need to address such health needs of women in prison even more important. In Burkina Faso, remand prisons with infirmaries provide curative care services to prisoners. However, they are neither sufficiently staffed nor equipped to deal with prisoners' sexual and reproductive health problems [2].

This study, which is the first of its kind in Burkina Faso, aims to explore the needs and supply of sexual and reproductive health services for women in prison settings in Ouagadougou. Therefore, it fills a major gap in the existing literature and could, in fact, serve to improve health services in penitentiary institutions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

Burkina Faso has three types of detention facilities: the Maisons d'Arrêt et de Correction (MACs), which are penitentiaries for persons awaiting trial and convicted persons; the Centres Pénitentiaires Agricoles (agricultural penitentiary centers), which receive convicted persons under the semi-liberty regime and the Centres de Re-education et de Formation Professionnelle (re-education and vocational training centres), which receive children convicted of crimes. There are 27 prison centres (MACs) and one agricultural prison centre in Baporo, and each prison centre has a section for minors.

The Ouagadougou prison is the largest prison in Burkina Faso. As mentioned previously, in 2018, it held 2,364 inmates, or 30.3% of the country's total prison population [3]. MACO is located in the city of Ouagadougou. Established in 1962, its structures were extended in 1994 and, in 2010, other 'quarters' were constructed to alleviate the difficulties of overcrowding and issues inherent in cohabitation between people of different ages and sexes. Since then, it has housed 5 wards: 2 adult male wards (a large building and a new building); one amendment ward (political prisoners' and businessmen's ward); one women's ward and one juveniles' ward. Despite this expansion, the problem of overcrowding remains. This, as expected, is not without health consequences for the prisoners [12].

Participants

The study was conducted at the Ouagadougou prison (MACO) and all its female inmates during the study period formed the study population. A clinical examination of the subjects was conducted to identify their health problems. The investigators were health workers who were specialized in sexual and reproductive health – including 2 gynecologists and 2 midwives mobilized by SOS medicine in collaboration with the Society of Obstetrical Gynecologists of Burkina Faso (SOGOB).

Type of study

A quantitative cross-sectional study was undertaken during the months of July and August in 2012 at the Maison d'Arrêt et de Correction de Ouagadougou (MACO) in Burkina Faso. Another descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted during the period from the 7th to 13th of October 2018.

Ethical considerations

This study was previously approved by the management of MACO. Throughout this period, all the imprisoned women were invited to take part in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and data confidentiality was ensured during data collection. Refusing to take part in the study did not lead to any sanctions whatsoever and was not reported to the prison management.

Collection process

Individual interviews were conducted with the inmates of the facility. For each inmate, the variables were socio-demographic characteristics, reasons for incarceration, sexual and reproductive health complaints, screening results for precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions, gynecological pathologies, management of diagnosed pathologies and routine care at the MACO infirmary (family planning, prenatal consultations, delivery, post-natal consultation, STI/HIV/AIDS prevention, management of gynecological pathologies).

Data analysis

Data entry was done using Epi-info. Descriptive analyses were undertaken with SPSS and consisted of simple frequency calculations.

RESULTS

During the period of our study, the total prison population was 2329 inmates with 67 women representing 2.9% of all inmates. We collected data from 54 women; 13 of them refused to participate, thereby representing a participation rate of 80.6% of women.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Women Inmates

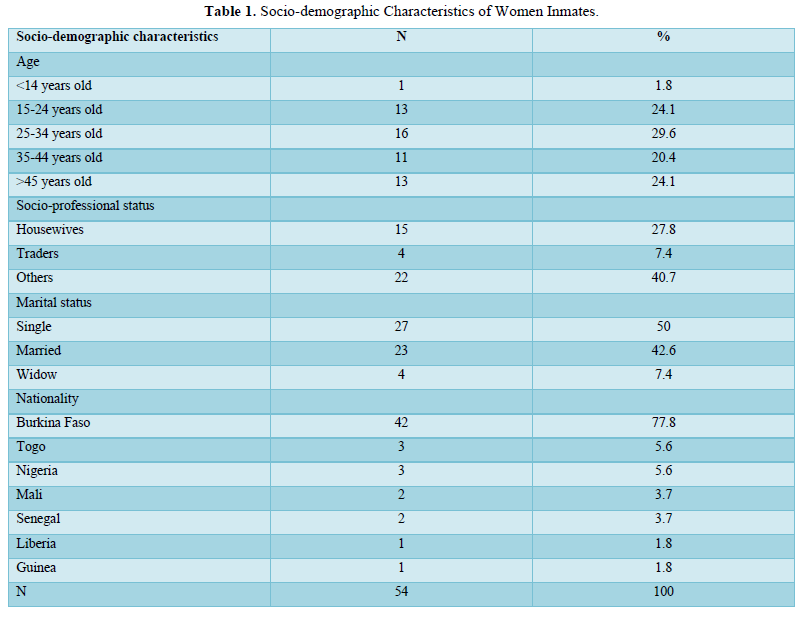

The ages of our clients ranged from 12 to 75 years with an average of 31.5 years. According to nationality, citizens constituted 77.8% and foreigners 22.2%. The socio-demographic characteristics of the inmates at MACO are recorded in Table 1.

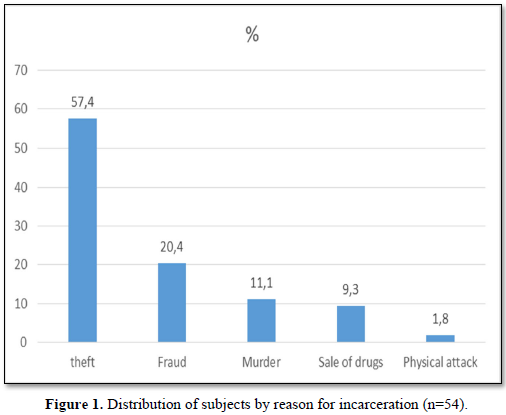

More than half (57.4%) of the inmates were incarcerated for theft and 20.4% for fraud (Figure1).

Reproductive Health Problems in Female Inmates

Complaints related to the sexual and reproductive health of women prisoners

Gynecological pathologies encountered

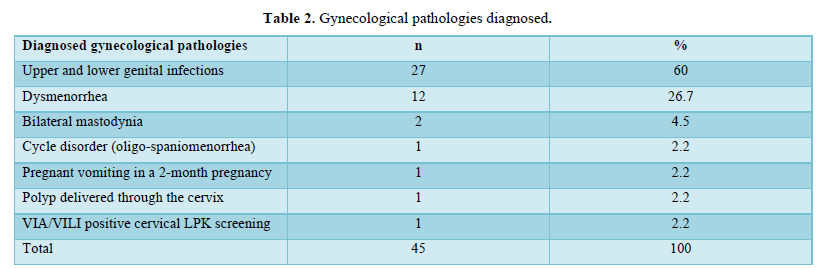

The gynecological pathologies observed during our study period are recorded in Table 2. The recurrent pathologies were upper and lower genital infections (60%) and dysmenorrhea (26.7%).

The management of gynecological pathologies in women was based on drug prescription in 35 women, polyp bistournage, cryotherapy for precancerous cervical lesion (VIA/VILI positive), one case of intrauterine device removal, and hygiene-dietary counseling. The drug prescriptions included analgesic/antispasmodic drugs in 24 women, antibiotics in 13 women, antimycotics in 07 women, antiparasitic drugs 11 women, antiemetics in 1 woman and oestrogen-progestin pills in 1 woman.

Provision of Reproductive Health Services at MACO

MACO's Nursing Care Services

The minimum activity package offered by the MACO care unit is essentially curative care. Cases of complications are referred to Saint Camille Hospital or the Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital Centre.

No family planning services are offered at MACO, and women prisoners reported never having heard of family planning at MACO. Monthly reports from the infirmary check-off for this activity. Moreover, it was found that no prenatal delivery and postnatal consultation services are available at MACO.

Prevention of STI/HIV/AIDS

With regard to this component, only the HIV/AIDS screening activity is carried out by some humanitarian NGOs at MACO.

DISCUSSION

In our study, the average age of the women was 31.5 years. This is not too far from the average age found by Ramaswamy [13] and Clarke [7], which were 33.9 and 30.7 years, respectively. The dynamism of the inmates in our study could be explained by the high level of physical and sexual activity in this age group and the greater need for health services appropriate to their needs, including sexual and reproductive health services. However, in the face of the difficulties of life, they are driven to wrongdoing by society in order to cling to the rhythm of life.

Women of childbearing age are a growing segment of the prison population, and many become pregnant while they are incarcerated [14]. In our study, one case (1.8%) of a 2-month pregnancy was noted. Our result is lower than that of Mignon [15] and Bronson [16] who, in their study, found that 3% and 5% of inmates respectively were pregnant at the time of incarceration. Among pregnant women entering state prisons, 94% underwent an obstetrical examination, but only 54% reported receiving prenatal care. In our study, activities such as prenatal visits were not conducted routinely; this points to a need to improve the provision of sexual and reproductive health services to women inmates.

Dysmenorrhea was present in 12 women (26.7%) in our study. Our results corroborate the data in the existing literature. Dysmenorrhea, which refers to painful menstruation, has a prevalence of 20%-90% in the female population [21,22]. Depression is cited as one of the risk factors for dysmenorrhea. Since our study was conducted in a prison setting, where most women are anxious, and which can be a source of depression, it may explain the onset of dysmenorrhea [22]. Genital infections that cause pelvic inflammatory disease and smoking are also some of the risk factors for dysmenorrhea [21]. In accordance with this, in our study, 60% of the women had a suspicion of upper and lower genital infections.

Bilateral mastodynia was found in 2 women or 4.5% of cases. Mastodynia, which is a functional sign that may indicate the existence of mammary pathology, was the reason for outpatient consultation at the CHUYO in 15.3% of cases [23]. Women in prison, as any female population, are also prone to various mammary pathologies. Hence, there is a need to take this population group into account in the provision of RH services.

In our study, one inmate or 1.8% of the respondents of VIA/VILI screened positive for precancerous lesions. Studies conducted show that cervical cancer is the most common cancer in prisons. The prevalence of CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) diagnosed by cytology in inmates ranged from 0% to 22%. Imprisoned women have a higher risk of cervical cancer than the general population. The prevalence of human papillomavirus infection and precancerous lesions was high in this population. Targeted programs for the control of risk factors and the development of more effective cervical cancer screening programs are hence recommended [24,25].

CONCLUSION

Prison inmates have numerous sexual and reproductive health needs. This study tells us that these incarcerated women do not have access to quality RH services as compared to other women in the outside world. Suggestions ranging from equipping them with quality human resources and medico-technical materials to meet their different sexual and reproductive health needs should be considered. The RH programs in place in the country should take the women in prison into account.

- Kouyoumdjian F, Schuler A, Matheson FI, Hwang SW (2016) Health status of prisoners in Canada: Narrative review. Can Fam Physician 62: 215-222.

- Bonkoungou J (2017) Surpopulation carcérale : Le Centre pour la qualité du droit et la justice veut y remédier, Lefaso.net.

- Ministère de la justice du Burkina Faso (2019) Annuaire statistique 2018.

- Ghana Ministries and Agencies of State (2020) Ghana prisons service.

- Barry LC, Adams KB, Zaugg D, Noujaim D (2020) Health-care needs of older women prisoners: Perspectives of the health-care workers who care for them. J Women Aging 32: 183-202.

- Liauw J, Foran J, Dineley B, Costescu D, Kouyoumdjian FG (2016) The Unmet Contraceptive Need of Incarcerated Women in Ontario. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada 38: 820-826.

- Clarke JG, Hebert MR, Rosengard C, Rose JS, DaSilva KM, et al. (2006) Reproductive health care and family planning needs among incarcerated women. Am J Public Health 96: 834-839.

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Parker S, Gjelsvik A, Mena L, Chan PA, et al. (2016) Condom use and incarceration among STI clinic attendees in the Deep South. BMC Public Health 16: 1-8.

- WHO (2009) Women’s health in prison.

- Dasgupta A, Davis A, Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, El-Bassel N (2018) Reproductive Health Concerns among Substance-Using Women in Community Corrections in New York City: Understanding the Role of Environmental Influences. J Urban Health 95: 594-606.

- Olugbenga-Bello AI, Adeoye OA, Osagbemi KG (2013) Assessment of the Reproductive Health Status of Adult Prison Inmates in Osun State, Nigeria. Int J Reprod Med 2013: 1-9.

- Zida A, Barro-Traoré F, Dera M, Bazié Z, Niamba P (2015) Aspects épidémiologiques et étiologiques des mycoses cutanéo-phanériennes chez les détenus de la maison d’arrêt et de correction de Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). J Mycol Med 25: e73-e79.

- Ramaswamy M, Kelly PJ (2015) Sexual health risk and the movement of women between disadvantaged communities and local jails. Behav Med 41: 115-122.

- Grassley JS, Ward M, Shelton K (2019) Partnership between a Health System and a Correctional Center to Normalize Birth for Incarcerated Women. Nurs Womens Health 23: 433-439.

- Mignon S (2016) A questão da saúde nas mulheres encarceradas nos Estados Unidos. Cienc e Saude Coletiva 21: 2051-2060.

- Bronson J, Sufrin C (2019) Pregnant Women in Prison and Jail Don’t Count: Data Gaps on Maternal Health and Incarceration. Public Health Rep 134: 57S-62S.

- Garaycochea CM (2013) Sexually transmitted infections in women living in a prison in Lima, Peru. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 30: 423-427.

- Vaz RG, Gloyd S, Folgosa E, Kreiss J (1995) Syphilis and HIV infection among prisoners in Maputo, Mozambique. Int J STD AIDS 6: 42-46.

- Montaño K (2018) Rapid diagnostic testing to improve access to screening for syphilis in prison. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 20: 81.

- Madariaga CFA, Garcés GBE, Parra CA, Foster J (2017) Sexuality behind bars in the female central penitentiary of Santiago, Chile: Unlocking the gendered binary. Nurs Inq 24: e12183.

- Osayande AS, Mehulic S (2014) Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician 89: 341-346.

- Speer L (2005) Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician 71: 285-291.

- Komboigo BE (2017) Pathologies mammaires dans le service de gynecologie du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Yalgado Ouedraogo: Epidemiologie, diagnostic et prognostic. J LA SAGO (Gynécologie-Obstétrique Santé la Reprod pp: 2.

- Brousseau EC, Ahn S, Matteson KA (2019) Cervical Cancer Screening Access, Outcomes, and Prevalence of Dysplasia in Correctional Facilities: A Systematic Review. J Womens Health 28: 1661-1669.

- Escobar N, Plugge E (2020) Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in imprisoned women worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 74: 95-102.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Advance Research on Endocrinology and Metabolism (ISSN: 2689-8209)

- International Journal of Diabetes (ISSN: 2644-3031)

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

- Journal of Oral Health and Dentistry (ISSN: 2638-499X)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- International Journal of Radiography Imaging & Radiation Therapy (ISSN:2642-0392)

- BioMed Research Journal (ISSN:2578-8892)