Research Article

Judicial Waiver Decision in the Tri-State Area: A Study of Judicial Perceptions

5802

Views & Citations4802

Likes & Shares

A review of the waiver literature reveals that it is not as well developed as the juvenile justice sentencing literature. This study contributes to contemporary research on judicial waivers by examining the relationship between individual characteristics of juvenile court judges and referees and their perceptions regarding judicial waiver. In determining these relationships, the analysis sought to answer the following question. Is there a difference in juvenile court judges’ perceptions about whether transferring juveniles to the adult criminal justice system deters crime based on age, gender, ethnicity, political party affiliation, tenure on bench, previous position held, and jurisdiction? A significant interaction was found for jurisdiction and previous position. The researchers acknowledge that there are differences in the definitions for the words transfer and waiver; however, to reduce confusion for the purposes of this study, the words waiver will be used for both. Suggestions for future research are offered.

Keywords: Waiver, Transfer, Juvenile court, Juvenile court judge, Juvenile justice

INTRODUCTION

From the inception of the juvenile court, judges have had the discretion to waive jurisdiction to the adult criminal court. Juveniles waived to the adult criminal court via judicial waiver generally fit one of three case types: serious offense, extensive juvenile record, or juvenile near the age limit. A judicial waiver occurs when a juvenile court relinquishes their right to prosecute the juvenile offender. When this right to prosecute is relinquished then the juvenile can be certified and tried as an adult.

The three types of judicial waiver are discretionary, presumptive, and mandatory. In discretionary waiver, juvenile court judges have the discretion to waive the case to the adult criminal court. At the end of 2009, there were 45 states that had the discretionary waiver mechanism [1]. In presumptive waiver, laws define which types of cases are presumed appropriate to waive from juvenile court to adult criminal court. The decision is in the hands of the judge; however, waiver is presumed. In presumptive waiver, the juvenile assumes the burden of proof to demonstrate why they should not be waived to the adult criminal court. At the end of 2009, there were 15 states that had the presumptive waiver mechanism [1]. Mandatory waiver applies to situations in which cases that meet certain criteria are waived to the adult criminal court. With mandatory waiver, a fitness hearing is conducted to determine whether the juvenile is “amenable to treatment” in the juvenile justice system. At the end of 2009, there were 15 states that had the mandatory waiver mechanism [1]. The most popular judicial waiver method is discretionary.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Fifty years ago, juvenile justice policy debates focused on issues of decriminalization of status offenses, due process, deinstitutionalization, and diversion. More recently, policy debates are focused on the question of whether serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders should remain in the

juvenile justice system or be waived to the adult criminal justice system.

Traditionally, the most popular method to waive has been the judicial waiver, which exists in forty-seven states and the District of Columbia. Juvenile court judges weigh a variety of factors in determining whether to waive a juvenile to the adult criminal court; however, the criteria for waiver are still not completely standardized because states have the ability to set age, offense, and other criteria governing the waiver of juveniles [1,2].

Deterrence Theory

There is conflicting empirical support for the deterrence theory, particularly when examining juvenile waiver. Overall, the research literature has elaborated on many of the concerns that are typically expressed about judicial waiver, including the belief that judges are vested with too much discretion, the belief that race influences the waiver decision; minorities are waived at a higher rate, that gender influences the waiver decision; males are waived at a higher rate, and that age influences the waiver decision; older juveniles are waived at a higher rate. Most studies would seem to suggest that waiving juveniles to the adult criminal court increases recidivism rather than reducing it [3-11]. In addition, these studies indicate that juveniles in adult correctional facilities suffer higher rates of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and suicide [12,13]. Furthermore, studies indicate that juveniles are being waived to the adult criminal court for less serious property and drug offenses thus making net widening a very real possibility [13-15]. Finally, studies indicate that juveniles waived to the adult criminal court can result in less punitive punishment, i.e., dismissals, plea bargains, diversion programs, and probation.

Judicial Waiver

A review of the waiver literature and in particular judicial waiver reveals that it is not as well developed as the juvenile justice sentencing literature. The judicial waiver literature tends to narrowly focus on the legal factors associated with juvenile waiver such as the seriousness of the offense, the need to protect the community, whether the offense was committed in an aggressive, violent, premeditated, or willful manner, whether the offense was against a person or property, the merit of the complaint, whether the juvenile’s associates will be tried in adult criminal court, the juvenile’s sophistication, maturity, record, and previous history, and the reasonable likelihood of rehabilitation. In addition, other extra-legal factors have been looked at such as the defendant’s age, race, gender, education status, family structure, and socio-economic status. What has not been examined are the judges’ perceptions, attitudes, and sanctioning ideologies with regard to judicial waiver and if there are a difference in the belief about how a judicial waiver affects juvenile crime based on individual characteristics of the juvenile court judges themselves.

Attitudinal Theory

Despite several decades of social science research on judicial decision making the literature is still incomplete. In particular, the impact of two variables is poorly understood; judges’ perceptions and sanctioning ideologies [17]. While there is research to suggest that perceptions and sanctioning ideologies are important predictors of behavior, no research has been successful in developing a single model incorporating perceptions and sanctioning ideologies and judges’ decision-making behavior [16-18].

Attitudinal theory asserts that an individual’s perceptions are shaped by their beliefs and values and are formed by their cumulative life experiences [19-21]. Attitudinal theory is defined as the physical expression of an emotion [16,17,19,22]. In 1934, LaPierre’s [23] study of hotel and restaurant personnel brought attitudinal theory to the forefront. There have been numerous studies conducted since the 1930s using attitudinal theory to show that individuals’ behaviors can be predicted based on their perceptions, and cognitive social psychologist believed that people with positive perceptions behave positively toward the attitude object [16,17,19,20,24].

Researchers Ajzen and Fishbein [19], Brigham and Wrightsman [17], Gibson [18], Pennington [18], Penrod [21] tend to agree that attitudes and/or perceptions are learned and differ according to an individual’s life experiences and cultural environment. It is these perceptions then that give rise to an individual’s intentions and determine an individual’s behavior [16-21,24]. Social Psychologists [18] assert that perceptions are extremely important because they are the key component in developing a complete understanding of an individual’s behavior.

There have been several studies Atkins [25], Atkins and Green [26], Atkins and Zavonia [27], Ajzen and Fishbein [19], Brigham and Wrightsman [17], Gibson [16], Howard [28], Pennington [18], Penrod [21] conducted using attitudinal theory to predict judges’ decision-making process. However, this research primary focuses on the Federal Court System and Federal Court judges. These studies suggested that although individual perceptions of the judges may influence their decisions, there are many other factors involved as well. Individual Supreme Court Justices consider the opinions of other members of the Court prior to making their decisions. This research does not apply to juvenile court judges’ decision making with regard to judicial waiver; thus, there is no further need to review such literature. However, there is research that has examined how particular characteristics; age, race, gender, political party, and jurisdiction, of the court judges affect their decisions making process [20,29-31].

First, age has been suggested to affect an individual’s decision-making process. Attitudinal theory asserts as an individual ages they accumulate life experiences. It is these life experiences that shape the individual’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Following this logic then, one could hypothesize that younger juvenile court judges have different life experiences than those who have been on the bench longer. Younger, i.e., newer, juvenile court judges would likely maintain different perceptions than older juvenile court judges regarding judicial waiver and punishment philosophies. As an individual grows older, he or she may adopt a more cynical attitude toward juvenile offenders [31]. However, Myers [30] reported just the opposite. He found that older judges handed down more lenient sentences than younger judges.

D’Angelo [20] in her dissertation, Juvenile court judges’ perceptions of what factor affects juvenile offenders’ likelihood of rehabilitation found that both male and non-minority judges perceive that extra-legal characteristics of juvenile delinquents: gender, race, social-economic status, location of residence, and family structure, affected efforts at rehabilitation. In addition, D’Angelo [20] found that a larger percentage of Democrats and Republican judges ranked socio-economic status as a very important factor for rehabilitation success. Furthermore, according to D’Angelo [20] all judges seem to believe that family structure and prior record are almost equally important. Finally, given these findings, D’Angelo [20] concluded that although juvenile court judges consider legal factors, they also include criteria that are not permitted by law in their waiver decisions.

D’Angelo [20] in her article Juvenile Court Judges’ Attitudes Toward Waiver Decisions in Indiana looked at gender and age as well as where the juvenile court was located to see what if any affects this may have on juvenile court judges’ perceptions of the factors, they believed should be used in their waiver decisions. There was no statistical significance between gender and the factors judges perceived to be important in making the decision to waive [20]. In addition, there was no statistical significance between age and the factors judges perceived to be important in making the decision to waiver; however, there was a statistically significant relationship between the location of the juvenile court and judges’ perceptions of factors they consider in their waiver decisions. D’Angelo [20] did not include race in her analysis due to the lack of non-minority judges.

D’Angelo [20] in her article, the complex nature of juvenile court judges’ transfer decisions: A Study of Judicial Attitudes looked at offender characteristics: age, gender, race, gang membership, family structure, type of abuse, and severity of abuse with respect to judicial waiver. She found that 58 percent of juvenile judges believe that age, gang membership, and a two-parent household are factors in the rehabilitation of juvenile offenders [20]. Furthermore, a substantial number of judges believe that juveniles who dropped out of school had less chance for success than those who graduated. This is consistent with other finds.

Similarly, race has been suggested to affect an individual’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Attitudinal theory asserts that non-minority juvenile court judges would have different life experiences than minority juvenile court judges. Therefore, non-minority juvenile court judges would likely maintain different perceptions than minority juvenile court judges. Following this logic then, one could hypothesize that non-minority and minority juvenile court judges would likely maintain different perceptions and sanctioning ideologies with regard to judicial waiver. Welch [32] found in his study that African American judges tend to hold more liberal views and therefore are more lenient than non-minority judges.

In addition, gender has been suggested to affect an individual’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Attitudinal theory asserts that male juvenile court judges would have different life experiences than female juvenile court judges. Therefore, male juvenile court judges would likely maintain different perceptions than female juvenile court judges. Following this logic then, one could hypothesize that males and female juvenile court judges would likely maintain different perceptions and sanctioning ideologies with regard to judicial waiver. Research by Erikson and Luttbeg [33] has shown that women are more liberal in their beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions. Furthermore, with respect to the issue of crime control, studies show that female judges are more lenient compared with male judges [34,35].

A large majority of research by Curtis [22], Gibson [16], Goldman [36], Nagel [37], Smith and Wright [38] has focused on the relationship between political party affiliation and judges’ decision-making process. Attitudinal theory would suggest that Republican and Democrat judges’ perceptions, attitudes, and sanctioning ideologies differ because they are likely to maintain different life experiences. Curtis [22] found that conservative judges tend to be more punitive than liberal judges. Other studies found that 82 percent of the Republican judges supported get tough punishment policies whereas only 50 percent of Democrat judges supported such policies [38,39]. Scholars suggest that Democrats tend to be more working class oriented in their perceptions, attitudes, values, and behavior than Republicans [16,37]. Therefore, scholars suggest that Democrat judges are more sympathetic to the plight of the lower and working class resulting in more lenient sentences [16,37].

Finally, cultural environment has been suggested to affect an individual’s decision-making process. Research found a relationship between the jurisdiction (i.e., rural v. urban) of the judges’ court and punishment severity [40-43]. They suggested that the culture of the surrounding area leads to differing perceptions, attitudes, and sanctioning ideologies between judges from rural and urban areas. In other words, the beliefs that shape an individual’s attitudes differ according to where he or she resides. Researchers found that judges from rural areas will impose more punitive penalties on female offenders than male offenders as compared with judges from urban areas. Such research suggests that rural areas maintain more traditional attitudes towards men and women’s roles in society [40-43]. Following this logic then, one could hypothesize that judges in jurisdictions that are rural have different live experiences than judges in jurisdictions that are more urban. Therefore, juvenile court judges in jurisdictions that are rural have different perceptions and sanctioning ideologies than juvenile court judges in jurisdictions that are more urban.

METHODS

This study sought to examine the relationship between individual characteristics of juvenile court judges and referees and their perceptions regarding judicial waiver. In determining these relationships, the analysis sought to answer the following question: Is there a difference in juvenile court judges’ perceptions about whether transferring juveniles to the adult criminal justice system deters crime based on age, gender, ethnicity, political party affiliation, tenure on bench, and previous position held, and jurisdiction? Additional questions asked juvenile court judges/referees the following:

- What, if any, problems exist with the use of judicial waiver?

- In your opinion, what are the strengths of the judicial waiver procedures?

- In your opinion, what are the weaknesses of the judicial waiver procedures?

- Do you have any additional comments on judicial waivers or deterring juvenile crime?

Given that there have been few studies on juvenile court judges’ and referees’ perceptions regarding judicial waiver this study was exploratory. The independent variables were age, gender, ethnicity, political party affiliation, tenure on the bench, previous position, and jurisdiction. The dependent variable was “juvenile court judges’ perceptions regarding judicial waiver”. The independent variable “Political party affiliation” was divided into three categories: Democrat, Republican, and Independent. “Tenure on the bench” was assessed in years. The “way in which the judge acquired his or her position” was divided into three categories; elected, appointed, and other. “Previous Position” was divided into three categories: prosecutor, defense attorney, and other. Age was assessed in years. Gender was dichotomized, male and female. Race was divided into five categories: White, not of Hispanic origin, Black, not of Hispanic origin, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander. Jurisdiction was divided into three categories: urban, suburban, and rural. The dependent variable “juvenile court judges’ perception regarding judicial waiver” was divided into five levels; Completely Agree, Agree, No Opinion, Disagree, and Completely Disagree.

Participants

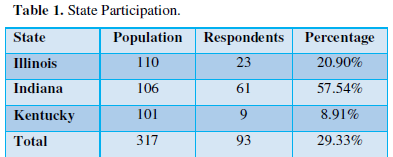

The population for this study consisted of all juvenile court judges and referees in the Tri-State area, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky. The nonrandom sampling technique used to select this population was purposive sampling. These states were chosen because they all utilized judicial waiver. The estimated total population for this study was 317. The expected rate of return for this study was set at 30 percent (n=95). The researcher came to this minimum acceptable return rate after reviewing literature on judicial return rates [20,44-47].

Instrumentation

The survey instrument for this study sought to assess judicial perceptions with regard to judicial waiver. The researcher developed the survey instrument based upon previous literature [46,20]. The instrument consisted of four sections: court information, sanctioning and disposition issues, demographic information, and qualitative strategy questions.

Procedures

A survey was mailed out to the juvenile court judges and referees in the Tri-State area, Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky. All survey responses were considered confidential and no individual identifiers were used. All surveys were destroyed once the analysis was completed. The survey was accompanied by a letter of explanation, an information sheet for consent to participate in a research study, and a self-addressed stamped envelope was provided to the participants. Participants were given the opportunity to receive via email a copy of the executive summary by responding to the email provided in the letter of explanation. If potential participants had not returned their questionnaires after two weeks, a follow-up letter was mailed to the non-respondents reminding them that their participation was greatly appreciated. If potential participants had still not returned their questionnaires after two weeks, a third and final follow-up letter was mailed to the non-respondents.

Data Analysis

All the data derived from the survey instruments was entered into SPSS 19.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the means, frequencies, and standard deviations for the demographic information collected from the participants in this study. The data was then analyzed using Chi-square. The alpha level for this study was set at .05.

RESULTS

Descriptive

Of the total population (N= 317), 93 juvenile court judges and referees returned usable questionnaires for an overall response rate of 29.33 percent (Table 1).

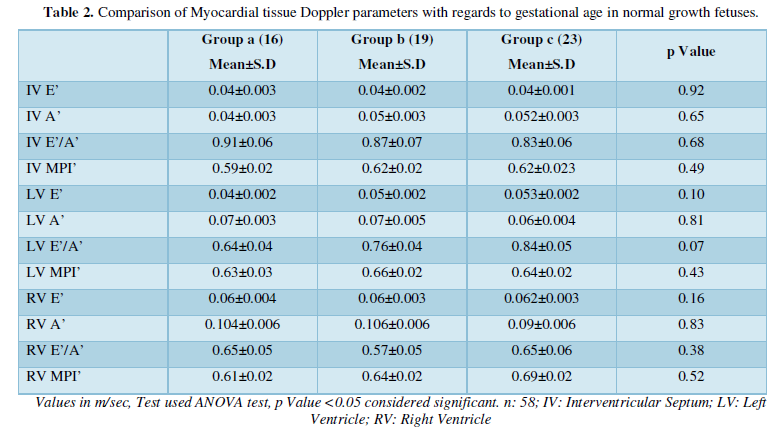

The 93 respondents ranged in age from 35 to 70. The mean age of the respondents was 57.53 with a standard deviation of 8.28 years. The descriptive statistics for the demographic questions are provided below in Table 2. This sample consisted of more males than females. Of the total respondents (n=93), 67 were male (72%). Regarding race, 92 respondents were white, not of Hispanic origins (99%). Of the 93 respondents, 24 were Democrats (25%), 41 were Republicans (44%) and 22 were Independent (24%). Of the 93 respondents 87 were judges (93%). The newest judge/referee in the group had been on the bench for one year. The judge with the greatest tenure in juvenile court had thirty-six years of experience. Of the 93 respondents, 67 were elected (72%) to the current post of juvenile court judge. Of the 93 respondents, 29 were prosecutors (31%) prior to becoming juvenile court judges, 32 were defense attorney (34%) and 32 were other (34%). Some examples of other previous positions held prior to becoming a juvenile court judge or referee were Civil Law Attorney, Federal Clerk, State Attorney, DCS Attorney, Divorce Court, and Private Practice. Finally, of the 93 respondents, 16 were located in an urban jurisdiction (17%), 18 were located in suburban (19%), and 59 were located in rural (63%).

Of the total respondents (n=93), 92 completely agreed/agreed that the primary goal of the juvenile justice system is rehabilitation (99%). Forty respondents (43%) did not believe that transferring juveniles to the adult system deters crime, 25 had no opinion (27%), and 28 completely agreed/agreed (30%). Fifty-Five of the 93 respondents (59%) believed that that judicial waives ensure community safety, 16 had no opinion (17%), and 22 completely disagreed/disagreed (24%). Sixty-six (71%) of the 93 respondents reported not considering public opinion in their decision to waive, 13 had no opinion (14%) and 14 admitted to considering public opinion (15%). Thirty-nine (42%) of the respondents reported considering their state’s “once and adult, always an adult” provision in their decision to waive. Fifty-one (55%) of the respondents had no opinion on rates of re-arrest being higher for juveniles who are waived to the adult system when compared to juvenile who remain in the juvenile justice system. Of the 93 respondents, 75 (81%) considered the recommendations of the juvenile probation officers in their decision to waive. Forty-one (44%) of the respondents did not believe juveniles who are waived to adult court have a higher likelihood of conviction than those who remain in juvenile court. Finally, sixty-two (67%) agreed that juveniles who are waived to adult court have a greater chance of incarceration than those adjudicated in juvenile court.

Statistical Analysis

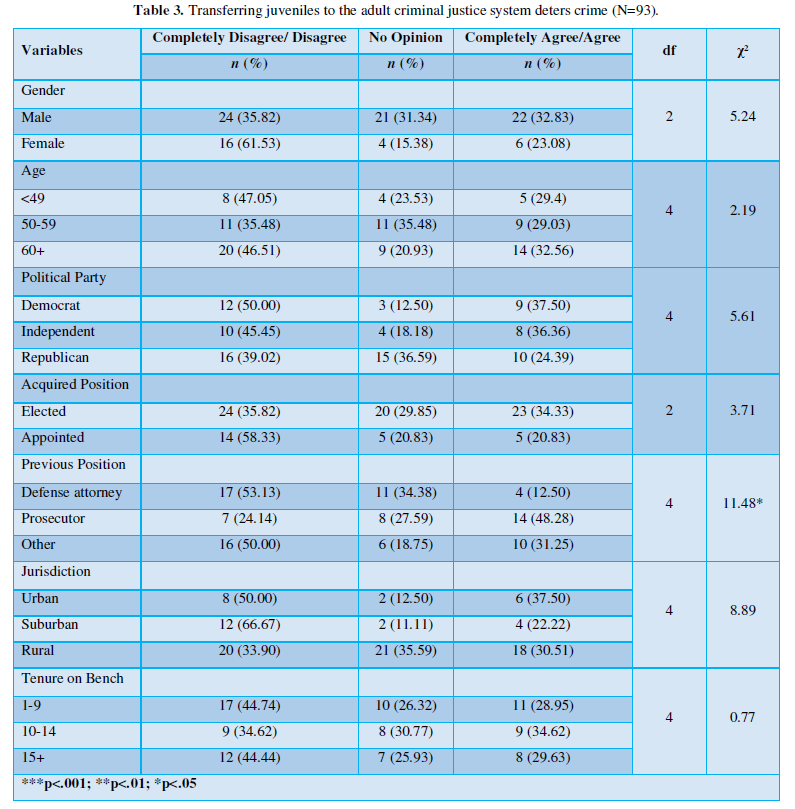

Chi-square tests of independence were used to understand the relationship between judicial perceptions with regard to judicial waiver and independent variables of age, gender, ethnicity, political party affiliation, tenure on bench, and previous position held, and jurisdiction. The dependent variable “juvenile court judge’s perception regarding judicial waiver” was collapsed into three categories; completely disagree/ disagree, no opinion, and completely agree/agree. The independent variables “age” and “tenure on the bench” were continuous, quantitative values that were arbitrarily divided. The chronological age range of the judges was divided into thirds creating categories of less than 49 (18%), 50-59 (33%) and 60+ years (46%). Two judges did not report their age (2%). Tenure in years was roughly divided into thirds creating categories of 1-9 (41%), 10-14 (28%) and 15+ (29%) years. Two judges did not report their tenure in years (2%).

Contingency tests were performed using Paleontological Statistics (PAST), version 3.05 that provided both Chi-square and Fisher’s exact values [48,49]. For significant results, standardized residuals are used in an informal manner to describe the pattern of association among the cells of a contingency Table 3 [50]. The equation for a standardized residual is the observed (fo) minus the expected (fe) values divided by the standard error (se). Agresti and Finlay [50] calculate the standard error (se) through the square root of the expected value multiplied by one minus the row proportion multiplied by one minus the column proportion.

z= (fo-fe)/se = (fo-fe)/√fe(1-row proportion)(1-column proportion)

Z-scores beyond ±2 provide evidence against independence in that cell, and values beyond ±3 are “very convincing evidence of a true effect in that cell” [50].

Of the 93 respondents, 92 were white, not of Hispanic origin (99%). Due to the lack of diversity, ethnicity was removed from the Chi-square equation. No significant relationship was found between age (χ²(4) = 2.19, p > .05), gender (χ²(2) = 5.24, p > .05), political party (χ²(4) = 5.60, p > .05), tenure on the bench (χ²(4) = 0.77, p > .05), way in which they acquired their position (χ²(2) = 3.17, p > .05), and jurisdiction (χ²(4) = 8.89, p > .05) (Table 3).

A significant interaction was found for previous position (χ²(4) = 11.48, p < .05; Fisher’s exact, p < .05). Juvenile court judges/referees who were previously defense attorneys were more likely to completely disagree/disagree (53%) with the statement Transferring juveniles to the adult criminal justice system deters crime, while those that were previously prosecutors were more likely to completely agree/agree with the statement (48%). Based on an analysis of standardized residuals, significantly more defense attorneys disagreed with the statement (z=+3.17), while significantly more prosecutors agreed with the statement (z=+2.57).

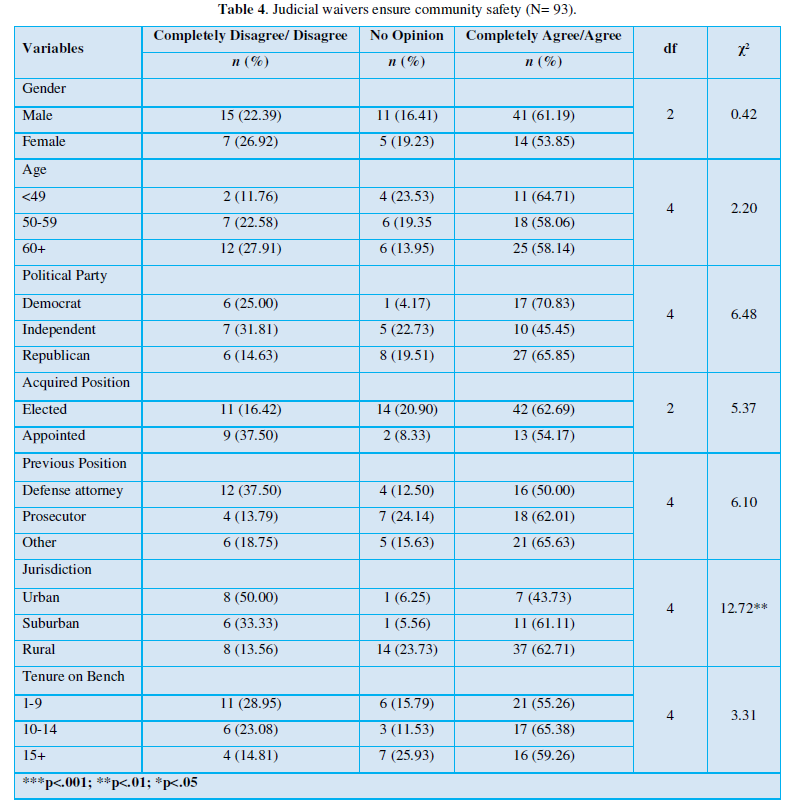

Of the 93 respondents, 92 were white, not of Hispanic origin (99%). Due to the lack of diversity, ethnicity was removed from the Chi-square equation. No significant relationship was found between age (χ²(4) = 2.20, p > .05), gender (χ²(2) = 0.42, p > .05), political party affiliation (χ²(4) = 6.48, p > .05), tenure on bench (χ²(4) = 3.31, p > .05), way in which they acquired their position (χ²(2) = 5.37, p > .05), and previous position held (χ²(4) = 6.10, p > .05) (Table 4).

A significant interaction was found for jurisdiction (χ²(4) = 12.72, p < .05; Fisher’s exact, p < .05). Rural (63%) and suburban (61%) judges/ referees were more likely to completely agree/agree with the statement “Judicial waivers ensure community safety”, while urban (50%) judges/ referees were more likely to completely disagree/disagree. Based on an analysis of standardized residuals, significantly more urban judges disagreed with the statement (z=+2.73). Although more suburban (z= +0.19) and rural judges (z=+0.92) agreed with the statement, the differences were not significant.

Participants were given the opportunity to provide their own comments regarding the judicial waiver process and deterring juvenile crime. Of the 93 respondents, 57 (61%) answered at least one of the four qualitative strategy questions. The juvenile judges and referees made numerous assertions with regard to judicial waivers and deterring juvenile crime. The juvenile court judges/referees did not appear to be opposed to the use of judicial waiver or in waiving juveniles to the adult criminal court; however, they asserted that juveniles should only be waived after there was the opportunity to review the juvenile’s entire history. Other responses to the qualitative strategy questions are as follows.

What, if any, problems exist with the use of judicial waivers?

- Lack of consistency and reliable data

- Petition to waive for less serious criminal acts poses a challenge.

- The proof of “beyond rehabilitation” in the juvenile system is difficult call.

- Exposing juveniles to adult incarceration, which negatively impacts the juvenile

- Possible racial and ethnic bias.

In your opinion, what are the strengths of the judicial waiver procedures?

- Allows for a full consideration and complete review of the serious offender by the state and is demonstrative of the juvenile efforts to reform behavior.

- Public awareness

- When judges have discretion

- Protect the community

- They allow the very serious matters to be handled in a more appropriate setting.

- The constitutional right to jury trial

- Usually only applied to repeat offenders or where multiple crimes alleged.

In your opinion, what are the weaknesses of the judicial waiver procedures?

- The length of sentence in the adult system without discretion to regular review for rehabilitation.

- It focuses more on punishment than providing services.

- The stigma: an error that would follow the child.

- They can be overused.

Do you have any additional comments on judicial waivers or deterring juvenile crime?

- The need to keep accurate data and statistics.

- The adult system is not set up to deal with the juvenile who is waived. Rehabilitation efforts are not as intense, and incarceration is not used due to the fear of a juvenile being with adults.

- Yes, stop the flow of heroin and marijuana to our children.

- Waivers do not deter juvenile crime. They are a “straw-that-broke-the-camel’s-back” last resort remedy for a habitually troublesome juvenile.

- More money needs to be spent on the juvenile justice system to increase available resources in order to eliminate waiver as a necessity.

CONCLUSION

The fact that this study found limited significant relationships is important. This study revealed that, in the Tri-State area: Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky, juvenile court judges and referees reported that they are not influenced by extra-legal factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, political party affiliation, and tenure on bench when making the decision to waiver a juvenile to the adult system. A significant interaction was found for previous position and jurisdiction. Chi-square tests for independence that were not significant tended to have medium effect sizes and powers below 80%. To increase power above 80%, sample sizes would need to be increased to over 107 for contingency tables with df =2 and 133 for contingency table with df=4 [51,52].

These findings provide some evidence that juvenile court judges are not ignoring or bending (belief that judges are vested with too much discretion) the due process requirements of the Fourteen Amendment as previous literature suggest but are in fact being objective in their use of judicial waiver. The results from this analysis indicate that juvenile court judges report that they are not influenced by extra-legal factors and make their decisions based on legally appropriate considerations suggesting that they are in the best positions to decide whether or not to waive juveniles to the adult criminal court, not the District Attorney or the Legislatures. Further analysis is needed to confirm this assertion.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The researchers make several suggestions for future research. First, the researchers suggest that additional states be included. The results of such a study would be more beneficial in terms of generalization. In addition, a follow-up study should be conducted using scenarios. The researchers suggest that scenarios be created or found and given to juvenile court judges. The juvenile court judges should be asked for their course of action to include the use of judicial waiver. This type of study would allow for between study comparisons and for a better understanding of juvenile court judge’s perceptions with regard to the use and deterring effect of judicial waiver.

In addition to the above recommendations for continued future research on judicial waivers, the researchers would suggest further research be conducted on the effect of probation officer sentencing recommendation on judicial decisions. The researchers asked the respondents the question, “Juvenile court judges consider the recommendation of the juvenile probation officer in their decision to waive.” Significant interactions were found for tenure on the bench (χ²(4) = 10.19, p < .05; Fisher’s exact, p < .05) and jurisdiction (χ²(4) = 16.15, p < .01; Fisher’s exact, p < .01). Although most judges either completely agreed or agreed with the statement, significantly more judges serving 10-14 years completely agreed with the statement (42%) (z = +2.72). In addition, significantly more suburban judges completely agreed with the statement (56%) (z = +3.72). Further analysis is needed to confirm this assertion.

- Griffin P, Addie S, Adams B, Firestine K (2011) Trying juveniles as adults: An analysis of state transfer laws and reporting (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention No. 232434). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice. Available online at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/232434.pdf

- NCJFCJ (2006) Juvenile Justice Reform Initiatives in the states 1994-1996. In Juvenile transfer to criminal court. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of Justice.

- Bishop DM, Frazier CE, Lanza-Kaduce L, Winner L (1996) The transfer of juveniles to criminal court: Does it make a difference? Crime Delinq 42: 171-191.

- Bishop DM, Frazier CE, Henretta JC (1989) Prosecutorial waiver: Case study of a questionable reform. Crime Delinq 35: 179-209.

- Lanza-Kaduce L, Lane J, Bishop DM, Frazier CE (2005) Juvenile offenders and adult felony recidivism: The impact of transfer. J Crime Justice 28: 59-77.

- Maitland AS, Sluder RD (1998) Victimization and youthful prison offenders: An empirical analysis. Prison J 78: 55-73.

- Mason CA, Chang S (2001) Re-arrest rates among youth incarcerated in adult court. Miami, FL: Miami-Dade County Public Defender's Office.

- McShane MD, Williams FP (1989) The prison adjustment of juvenile offenders. Crime Delinq 35: 254-269.

- Myers DL (2001) Excluding violent youths from juvenile court: The effectiveness of legislative waiver. New York: LFB Scholarly.

- Myers DL (2003) Adult crime, adult time: Punishing violent youth in the adult criminal justice system. Youth Violence Juv Justice 18: 173-197.

- Winner L, Lanza-Kaduce L, Bishop DM, Frazier CE (1997) The transfer of juveniles to criminal court: Reexamining recidivism over the long term. Crime Delinq 43: 548-563.

- Frost M, Fagan J, Vivona TS (1989) Youth in prisons and training schools: Perceptions and consequences of the treatment custody dichotomy. Juv Fam Court J 40(1): 1-14.

- Lawrence R, Hemmens C (2008) Juvenile justice a text/reader. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Butts JA, Mitchell O (2000) Brick by brick: Dismantling the border between juvenile and adult justice. In C. M. Friel (Ed.), Boundary changes in criminal justice organizations. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice. 22: 167-213.

- Myers DL, Kiehl K (2001) The pre-dispositional status of violent youthful offenders: Is there a "custody gap" in adult criminal court? Justice Res Policy 345(12): 115-143.

- Gibson JL (1978) Judges' role orientations, attitudes, and decisions: An interactive model. Am Pol Sci Rev 72(3): 911-924.

- Brigham J, Wrightsman L (1982) Contemporary issues in social psychology. Monterey, CA: Brooks and Cole.

- Pennington D (1986) Essential social psychology. London: Edward Arnold.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1977) Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol Bull 84(5): 888-918.

- D'Angelo JM (2000) Juvenile court judges' perceptions of what factors affect juvenile offenders' likelihood of rehabilitation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, American University, College of Arts and Sciences.

- Penrod S (1986) Social psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Curtis MS (1991) Attitude toward the death penalty as it relates to political party affiliation, religious belief, and faith in people. Free Inq Creat Sociol 19(2): 205-212.

- LaPiere RT (1934). Attitudes v’s actions. Soc Forc 13: 230-23

- D'Angelo JM (2007) The complex nature of juvenile court judges' transfer decisions: A study of judicial attitudes. J Soc Sci 44: 147-159.

- Atkins B (1974) Opinion’s assignment on the United States court of appeals: The question of issue specialization. West Pol Quarterly 27: 409-428.

- Atkins B, Green J (1976) Consensus on the United States court of appeals: Illusion or reality? Am J Pol Sci 20: 735-748.

- Atkins B, Zavonia W (1974) Judicial leadership on the court of appeals: A probability analysis of panel assignment in race relations cases on the fifth circuit. Am J Pol Sci 18: 701-711.

- Howard JW (1981) Courts of appeals in the federal judicial system: A study of the second, fifth, and District of Columbia circuits. Princeton: Princeton University.

- D'Angelo JM (2007) Juvenile court judges' attitudes toward waiver decisions in Indiana. Prof Iss Crim Justice 2(2).

- Myers M (1988) Social background and the sentencing behavior of judges. Criminology 26: 649-670.

- Schwartz IM, Shenyan G, Kerbs JJ (1993) The impact of demographic variables on public opinion regarding juvenile justice: Implications for public policy. Crime Delinq 39(1): 5-28.

- Welch S, Combs M, Gruhl J (1988) Do black judges make a difference? Am J Pol Sci 32: 126-135.

- Erikson RS, Luttbeg NR (1973) American public opinion: Its origins, content, and impact. New York: Wiley.

- Gruhl J, Spohn C, Welch S (1981) Women as policymakers: The case of trail judges. Am J Pol Sci 25: 308-322.

- Krtizer HM, Uhlman TM (1977) Sisterhood in the courtroom: Sex of the judge and defendant in criminal case disposition. J Soc Sci 14: 77-88.

- Goldman S (1975) Voting behavior on the U.S. courts of appeals revisited. Am Pol Sci Rev 69: 491-506.

- Nagel S (1961) Political party affiliation and judges' decisions. Am Pol Sci Rev 55: 843-850.

- Smith MD, Wright J (1992) Capital punishment and public opinion in the post-Furman era: Trends and analysis. Sociol Spect 12: 127-144.

- Taylor V (1989) Social movement continuity: The women's movement in abeyance. Am Sociol Rev 54(5): 761-775.

- Feld BC (1991) Justice by geography: Urban, suburban, and rural variations in juvenile justice administration. J Crim Law Criminol 82: 156-210.

- Johnson DR, Scheuble LK (1991) Gender bias in the disposition of juvenile court referrals: The effects on time and location. Criminology 29(4): 677-699.

- Myers M, Talaricco S (1986) The social contexts of racial discrimination in sentencing. Soc Problem 33(3): 236-251.

- White L, Booth A (1978) Rural-urban differences in Nebraska: Debunking a Myth. In Nebraska Annual Social Indicators Survey (Bureau of Sociological Research No.5). Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

- Cruz SJ (1998) Perspectives from the bench: A look at Alabama juvenile court judges. Unpublished Thesis, Jacksonville State University, Criminal Justice Department.

- Cruz SJ (2011) From juvenile court to the adult criminal justice system: An examination of judicial waiver. (Doctoral dissertation). The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS.

- Hays S, Graham CB (1993) Handbook of court administration and management. New York: CRC Press.

- Keenan SJ, Rush JP, Cheeseman KA (2015) Judicial waiver decisions in two southern states: A study of judicial perceptions. Am J Crim Law 40(1): 100-115.

- Hammer O (2015) PAST version 3.05. Accessed on: February 22, 2015. Available online at: http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/

- Hammer O, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Available online at: https://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/past.pdf

- Agresti A, Finlay B (2009) Statistical methods for the social sciences. 4th Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

- Myers DL (2003) The recidivism of violent youths in juvenile and adult court: A consideration of selection bias. Youth Violence Juv Justice 181: 79-101.

- Myers DL (2005) Boys among men trying and sentencing juveniles as adults. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Spine Diseases

- Journal of Immunology Research and Therapy (ISSN:2472-727X)

- International Journal of Anaesthesia and Research (ISSN:2641-399X)

- International Journal of Clinical Case Studies and Reports (ISSN:2641-5771)

- Journal of Renal Transplantation Science (ISSN:2640-0847)

- Journal of Clinical Trials and Research (ISSN:2637-7373)

- Oncology Clinics and Research (ISSN: 2643-055X)