Research Article

MERCHANTS AND BELIEVERS: RELIGIOUS TOURISM AND THE BUSINESS OF FAITH

1177

Views & Citations177

Likes & Shares

Religious tourism is a phenomenon that in the Los Altos de Jalisco region has found a fertile field since the seventeenth century with the emergence of devotion to the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos, and which has increased since the year 2000. the influx of visitors due to the canonization of the Cristeros martyrs, this has resulted in an official tourist promotion program called "Cristero route" and the emergence of new centers of religious devotion that only in the case of Santa Ana de Guadalupe receives approximately one million visitors a year.

Therefore, in this article the objective has been to show some relevant aspects about how the tourist vocation based on religious factors has developed in the Altos de Jalisco area. For this, a qualitative methodology has been used to review scientific articles about religious tourism, as well as a review of tourism policies in Jalisco related to religious tourism.

Among the main conclusions that could be obtained from this research, it is found that the tourist infrastructure of religious sites is very precarious and it is necessary to try to improve it so that they are no longer only places of faith and are spaces of tourist attraction.

Keywords: Religious tourism, Altos de Jalisco, Cristero route, Economy, Religion

INTRODUCTION

Religion is a phenomenon that has been associated with humans since time immemorial, so the interest in knowing and visiting places considered sacred has an ancient history (Lanquar & World Tourism Organization, 2007), the mobilization of people from a population or region to another for religious reasons is not something new, however, the value that this type of tourism really has has not been given because it does not respond in general terms to the principles of marketing that seeks to stimulate the desire of a person to visit or know a specific tourist destination (Aulet & Vidal, 2018; Enríquez Acosta et al., 2017; Esteve Secall, 2009).

Since the motivation of tourists who visit religious centers is not necessarily promoted by marketing in principle, these sites become of little interest to tourist agents; But the disdain for these types of destinations does not minimize the importance of religiously motivated tourism

“The centers of religious worship receive between 220-250 million people, of which approximately 150 million, that is 60-70 percent, are Christians. It is also estimated that in Europe alone, around 30 million Christians, especially Catholics, spend their holidays (or part of them) to go on a pilgrimage. In Poland alone, about 5 - 7 million people participate each year in pilgrimage migrations (more than 15 percent of the population)” (Asamblea Legislativa del Distrito Federal, 2012).

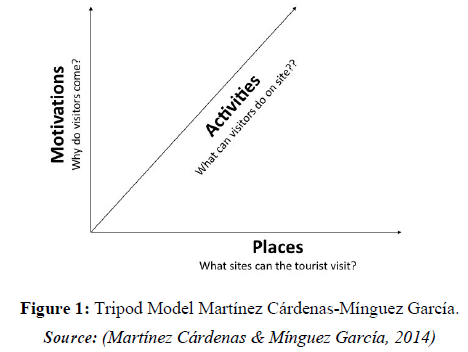

The tourist heritage that a population has must include two aspects: a) the spatial environment and b) the products offered in that space. When we refer to the spatial field, we speak of the space in which the tourist activity takes place, where the importance of the territory, the environmental resources such as the climatic and geographical perspective are highlighted.

When we talk about the products that are offered, we refer to the tourist infrastructure which includes all types of facilities in the destination that facilitates the level of enjoyment of the resources, such as hotel facilities, means of communication, the cultural heritage represented. for its museums and other places that come to represent a legacy of the past in force today (Andrés Sarasa & Espejo Marín, 2006; Machado Chaviano & Hernández Aro, 2007; Martínez Cárdenas & Mínguez García, 2014) (Figure 1).

OBJECTIVE

The present work aims to show some relevant aspects about how the tourist vocation based on religious factors has developed in the Altos de Jalisco area.

METHODOLOGY

To carry out this research, a careful analysis was used by reviewing scientific articles published on religious tourism, religious marketing and the Altos de Jalisco region, and on public tourism policy in aspects of religious tourism. Subsequently, the statistical yearbooks of tourism in the Altos de Jalisco region were reviewed and finally a physical visit was made to Santa Ana de Guadalupe, where Santo Toribio Romo is venerated.

The region of Los Altos de Jalisco, Mexico

Referring to the region of Los Altos de Jalisco is talking about a region that has been mythologized by Mexican cinema by turning it into the space where several stories were developed in a filmography that spreads an idyllic and romantic image of the "charro" man who works the countryside, with its brave temper, of the Mexican countryside with its “haciendas” (large rural farms), in addition to the mariachi as an image of the Mexican.

These films were set to songs such as: Esos Altos de Jalisco, Las Alteñitas, Atotonilco, etc., which have been around the world as classic songs of Mexican music. However, the reality is that Los Altos de Jalisco is not a space that preserves these great "haciendas" and hence there is no relevant heritage of this type to offer visitors, colonial-type buildings with the exception of those located in the town of Lagos de Moreno, are scarce in the area, so they do not present an opportunity to bring visitors to this region.

However, the geographical position of Los Altos made them play an important role during the colony, since it served as a supply area to the mining regions, as well as a refuge in the transit of gold shipments that traveled to Mexico City (Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, 2006). Likewise, the route that communicated New Spain with the Philippines passed through this region, but despite its geo-economic importance (UNESCO, 2010) it remained a territorial space alien to warlike conflicts such as independence, reform or revolution and it was even almost forgotten, until the Christianity made the national gaze set its eyes on this region (Martínez Cárdenas & Reynoso Rábago, 2019a).

But despite not having a powerful environmental attraction or a heritage wealth with recognized architectural or historical value, for tourism to seek the Altos de Jalisco as a tourist destination, it has since the seventeenth century a religious potential that has allowed it to have an important flow of visitors during all this time (Martínez Cárdenas & Reynoso Rábago, 2019b).

The religious phenomenon has taken on an increasingly important dimension in recent years, not only as a sociological or anthropological phenomenon, but also due to its impact on an economic level, to the extent that it has been viewed as a model of economic growth in some regions and as a a tourism promotion strategy by the government sector.

The economic spillover generated by this fact has effects on the populations where a saint or blessed is venerated, it must be clarified that the phenomenon does not refer only to the faithful who profess the Catholic religion, but to any type of cult, even when in the case of the state of Jalisco, government support has been given to those demonstrations associated with Catholic devotion for being predominant among the population (Martínez Cárdenas & Mínguez García, 2019).

Hence the importance of studying tourism as an economic phenomenon, without this meaning separating it from its sociological and anthropological environment. And it is that the market - global, neoliberal and of mass consumption - indefinite entity that has gained relevance as an autonomous social system, oblivious to the public policies of any nation-state that impregnates other fields or social systems with its logic. succeeded in transforming religion itself.

And it is that the religious cannot be defined solely by means of organized and institutionalized manifestations and beliefs (religions). “The religious is a transversal dimension of the human phenomenon, which crosses, actively or latent, explicitly or implicitly, the entire thickness of social, cultural and psychological reality according to the modalities of each of the civilizations, within which strives to identify their presence” (de la Torre Castellanos & Zúñiga, 2005).

Contemporary man faces, unlike the past, a diversity of religious offers, which compete with each other looking for believers to adhere, just as companies do, since radio and television advertising schemes and even spectacular advertisements are already used. under a liberal supply and demand scheme, with which religions progressively lose their mandatory character to become an option of individual choice based on the freedoms that allow for their practice or permissibility to carry out certain types of actions in pursuit of personal benefit or pleasure.

This new situation leads us to inquire about the mediations between the market logic and the logic of religious beliefs and experiences, in order to explore the new situations, places, agents and rituals that delineate the production, circulation and consumption of the sacred in our days (Martínez Cárdenas & Ruiz Aguirre, 2021). This raises new questions: to what extent is contemporary religiosity lived and experienced through the consumption of cultural merchandise? In what ways is popular religiosity reorganized around consumption itineraries? How do religious symbols circulate in markets and supermarkets? In short, what types of religiosities is shaping this new mediation of commodification of contemporary religiosity? (de la Torre & Gutiérrez Zúñiga, 2005).

Marian origins in Los Altos de Jalisco

Marian devotion is promoted by the first evangelizers who arrive in the region, in fact it is attributed to the friar Miguel de Bolonia the fact of leaving in that population an image of the Virgin Mary made in paste and which was venerated in a hermitage of adobe with a grass roof twenty yards long and eight wides, an effigy that is popularly known today as the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos (Ruezga Gutiérrez & Martínez Cárdenas, 2011).

Los Altos become important for New Spain because it was in the supply strip for the Zacatecas mining areas (later the commercial flow that this region would have with the east through the port of San Blas would also be important), and echoing A papal design, King Carlos V authorized in the year 1548 the creation of the Audiencia de la Nueva Galicia with headquarters in the city of Guadalajara, since already in the year 1546 Pope Paul III had erected the bishopric of the same name , by means of the papal bull "Super specula".

However, Guadalajara is far from the Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí mines, so it becomes a necessity to found new towns closer to the mines.In the year 1563 the parish of Santa Maria de los Lagos was born, and by 1572 San Salvador de Jalostotitlán that were the two ecclesiastical heads that comprised the Villa of Santa María de los Lagos.

What is now known as San Juan de los Lagos and previously as San Juan Bautista Mezquititlán was a civil dependency of Santa María de los Lagos and ecclesiastically of San Salvador de Jalostotitlán, the population of San Juan was Tlaxcalteca according to the studies carried out by Fabregas Despite not having a population of Spanish origin and having only a small number of grass-roofed huts, little by little it was gaining importance due to its geographical location, since it was within the commercial route of San Luis, Zacatecas, Guadalajara. , San Blas and it was an obligatory resting point.

From the year 1623 (other versions mention the year 1630[1] as the date of this event) there is a rumor that a miracle had occurred in the town of San Juan which was attributed to a little virgin who was venerated in that place. From that moment, a continuous pilgrimage of people who intend to ask for the grace of this image or give thanks for the favors received begins.

"The church and the enriched ranchers found the most effective mechanism to displace the indigenous population at the same time that they made the place famous: they invented for the modest local Cihuapilli a spectacular and miracle to turn it into Our Lady of San Juan." (Fábregas, 1986)

“Very soon two pious customs were formed: one of making a gift to the Blessed Virgin, either in money, or in some candles - which were too expensive and scarce at the time - either in jewelry, or in wax, silver or gold votive offerings. , well in objects destined for worship. " (Márquez, 1947)

The devotion to this image grew more and more so that Br. D. Diego Camanera, parish priest of Jalostotiltlán, undertakes the task of building the first temple for the Virgin of San Juan. In the year 1655, the landowner Don Juan de Espíndola and his wife Doña Catalina López de Baena, living in Mexico City, donated a thousand belly and scissor sheep to the sanctuary of San Juan de los Lagos to celebrate the feast of the Assumption of Mary. Santísima with vespers and a very solemn mass with loan, deacon, subdeacon and procession. (Ruezga Gutiérrez & Martínez Cárdenas, 2011)

In 1693, the priest Nicolás Arévalo sent a report to Bishop León y Garabito at the request of the latter on the invocation of María Santísima who was venerated in the town of San Juan de los Lagos, where he affirms that on the day of the main festival there were about thirty priests and three to four thousand people so they did not fit in the houses of the town, which is why they had to stay in tents out in the open.

“In that time of piety and fervor, the Pilgrim Image was received everywhere with unusual displays of joy: wherever he wanted, large donations were made to him; and his visit was regarded as an inestimable benefit. Later they began to request from different places at the same time, and in the impossibility of taking it everywhere it was decided to make another copy of the original; another collector was appointed, and the two Images traveled at the same time, although separated, the different provinces of New Spain” (Márquez, 1947)

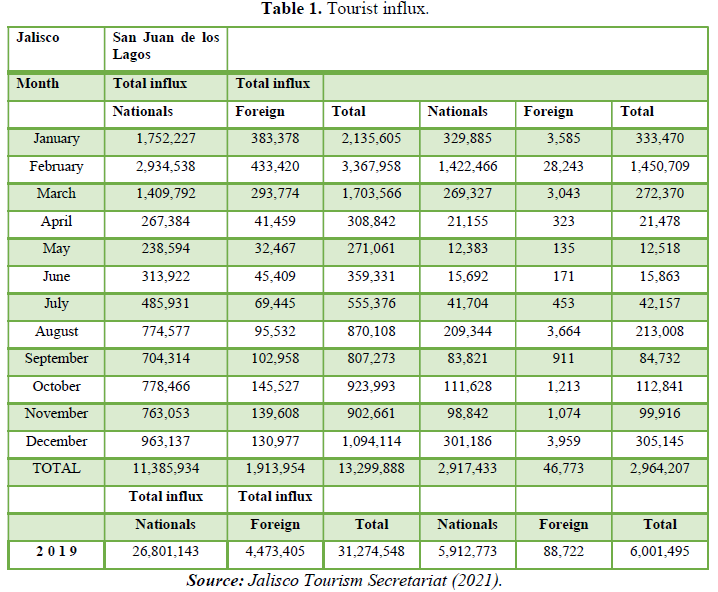

The feast of the Assumption of Mary continued to be celebrated until the year 1666, when the priest in charge of the temple of San Juan, Verdín de Molina, decided that it should be venerated under the invocation of the Purísima whose feast is on December 8, arriving pilgrims from the towns of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Puebla on the occasion of the festival. The change of dedication (from Virgen de la Asunción to Virgen de la Purísima) and the modification of the date of the celebration (from August 15 to December 8), did not matter (Table 1) much to the people, since for the year 1693 the Senior chaplain of San Juan Nicolás Arévalo reported to Bishop León and Garabito “about thirty priests and an influx of three to four thousand people attended the main festival, plus they did not fit in the houses of the town and stayed in camping houses that they brought to take shelter from the elements ” (Márquez, 1947) Bishop Diez de Sollano arguing that the commercial fair that took place in San Juan de los Lagos on the occasion of the religious festival caused disorder and vices in the population changed the date of the feast of the Virgin on February 2, which continues to be celebrated to date.

Just for the Candelaria festival, it is estimated that 2 million people arrive in San Juan de los Lagos and another 4 million throughout the year. These visitors come mainly from the State of Mexico and the Federal District. Since 2020 there has been a decrease in visitors, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new local saints

The armed movement of religious origin known as “la cristiada”, despite the fact that for a long time it was not recognized as part of the official Mexican history, it significantly marks the Mexico of the twentieth century. Some of its actors become crucial characters in political and ideological aspects of current Mexico in a post-conflict date. On the official side, we can mention two generals of the Mexican national army, who were in command of fighting the Cristeros armed groups that come to occupy the presidency of the republic, they are Lázaro Cárdenas, who is a milestone in recent national history. and Manuel Ávila Camacho.

The Cristero ideology continued in force after the war and was incorporated into political groups such as the Mexican Democratic Party (now defunct) and the National Action Party, which in recent years, with the spread of economic neoliberalism as the dominant ideology at the international level, has taken great strength to the degree that he obtained the presidency of the republic in the year 2000.

After seventy years of the church-government confrontation, Pope John Paul II recognized some priests as worthy of being saints for the Catholic Church (under the merit of defending the faith in the face of attacks against the government[1]). and lay people who were martyred during the “Cristero” conflict, for which, on May 21, 2000, he canonized the following people of El Alto origin or those who died for religious reasons in that region: Atilano Cruz Alvarado, Román Adame Rosales, Julio Álvarez Mendoza, Pedro Esqueda Ramírez, Toribio Romo González, Justino Orona Madrigal, Tranquilino Ubiarco Robles, Sabás Reyes Salazar, José Isabel Flores Valencia.

This fact, came to rekindle the manifestations of faith among an important part of the population. Since the territorial identification and in some cases the real or idealized consanguinity, has generated a great devotion to these new saints, in places such as: Santa Ana de Guadalupe, Jalostotitlán municipality (Temple of Padre Toribio), La Peñita, municipality of San Diego de Alejandría (Temple of Christ the King and his monument), Cañada de Islas, municipality of Yahualica (Temple monument to Christ the King), Teocaltitlán de Guadalupe, Municipality of Jalostotitlán (Temple to San Pedro Esqueda), Tepatitlán (sacrifice site of San Tranquilino Ubiarco), San Julián (Chapel of San Julio Alvarez), Yahualica (Parish Temple of San Román Adame) and Encarnación de Díaz (“Efrén Quezada” National Cristero Museum)

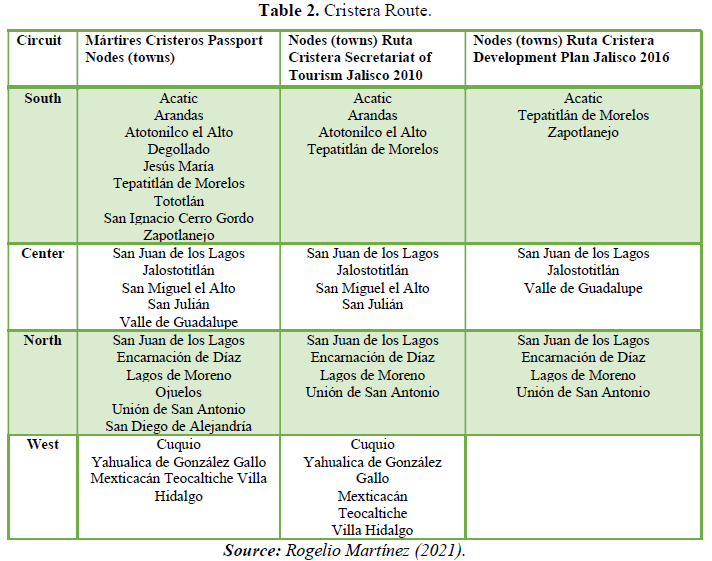

Given the interest of a significant number of people to visit these new religious centers, the Ministry of Tourism of the state of Jalisco has developed and promoted what has been called the "Cristera Route" whose main objective is that tourists visit these places of Catholic religious devotion.

The route has had modifications over time as shown in the following (Table 2).

The secretariat of tourism has tried to make religious visitors stop visiting only the town of San Juan de los Lagos and begin to move to other nearby sites seeking that they also benefit from the economic spill that these visitors could leave, the case The most representative is that of Santa Ana de Guadalupe where Santo Toribio Romo is venerated.

However, since the tourist for religious reasons does not attend with cultural interest, but devotional, they do not care about the additional tourist attractions offered by the visited populations, hence the proposal of the tourism secretariat has not been successful. That is why the case of the sanctuary of Santo Toribio Romo is interesting.

Saint Toribio Romo, like the other canonized martyrs, is credited with having performed the miracle of the healing of a person, which is why, according to the Catholic Church, they achieve the merit of holiness (the beatification was obtained by demonstrating that they died in defense of the faith), however, another miracle is also popularly attributed to him, the Catholic Church has not made an official pronouncement in favor or against; The anecdote refers to the fact that he personally helped a migrant to cross the border when he no longer had the economic resources to pay his expenses, so he is colloquially known as the “patron of migrants”, a fact that has given him great popularity in By virtue of the fact that the Altos de Jalisco has been an area of migrants for several generations.

The sanctuary of Santo Toribio Romo is located in Santa Ana de Guadalupe, delegation of the Jalostotitlán municipality (remember that San Salvador de Jalostotitlán was one of the first parishes in Los Altos, it was born in 1546) is a town that due to its location allows easy access from the cities of Guadalajara (approximately one hour and thirty minutes), of León, Guanajuato (approximately one hour and thirty minutes) and Aguascalientes (approximately two hours).

Until recently this population was a rural hamlet that did not have basic public services, since the public lighting system was only provided to them in the eighties of the 20th century, however, since 2000 it has created a incipient infrastructure to receive pilgrims who visit that place; an estimated 3,000 people attend each weekend and 1,000 on weekdays.

Its streets that until recently were dirt, today has asphalt, the road that connects it to the highway that goes from Jalostotitlán to San Miguel el Alto was expanded to have the capacity to circulate two vehicles, also a paved road was built that It ends at the steps of the temple and there are two large parking areas to meet the demand for cars and buses that arrive at the site.

With the intention of offering tourists more alternatives than just visiting the sanctuary, the "John Paul II" museum was built where some religious relics are kept. This continuous flow of pilgrims has become a potential market for potential consumers, which is why a series of souvenir and food businesses for tourist consumption have appeared, as well as all kinds of products with the image of Santo Toribio Romo, from novenas to keychains, t-shirts, fistoles, medals, glasses, pictures, etc. which are purchased by tourists on average between 120 and 150 pesos, which means an estimated economic spill of more than 25 million pesos per year (Martínez Cárdenas, 2013) (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

Religious tourism is a phenomenon that mobilizes a large number of people not only in Mexico, however, in our country the main centers of devotion are associated with the Catholic religion and located in the central western region (which corresponded to the kingdoms of Mexico and New Galicia of New Spain of the time in Spain conquered America) although others of great importance that do not belong to this religion as in the case of the Beautiful Province that is also located in the same geographical area, since it is located in the city of Guadalajara, Jalisco, however, is not considered as a promotional point within the official policy of the Ministry of Tourism of the state of Jalisco.

Los Altos de Jalisco has found within the tradition of visiting devotional sanctuaries and temples an opportunity to develop a tourist corridor that, more than responding to people's leisure needs, is associated with a cultural tradition that has its origins in the Spanish conquest. when the Catholic religion is imposed as the official religion.

Even though religious tourism is considered unattractive by tourist operators because the expense generated by each person is small compared to beach tourists, the volume of pilgrims who go to these places makes this an interesting option for the populations. recipients of this type of visitor.

However, it also poses a challenge for these places, since they need to create a tourist infrastructure that allows them to offer visitors adequate facilities for the needs they demand, in the case of San Juan de los Lagos, only the parking places represent a problem due to their scarcity and the high cost of those that exist.

Such is the challenge posed by the physical adaptation of the places that house devotion centers that San Juan de los Lagos has been debating for several years the possibility of developing a suitable space for the devotional influx that is received in a place outside the downtown area. of the population, however, the main opponents are the tenants who are around the parish due to the effects on the drop in sales they would have and the decrease in the cost per square meter of the premises and land located in that area.

- Andrés Sarasa, J.L., & Espejo Marín, C. (2006). Interacción mito religioso producto turístico en la imagen de la ciudad Caravaca de la Cruz (Murcia). Cuadernos de Turismo 18, 7-61.

- Asamblea Legislativa del Distrito Federal. (2012). LEY DE PROTECCIÒN DE LOS DERECHOS DEL PEREGRINO. Gaceta Parlamentaria de La ALDF 30(1), 1-17.

- Aulet, S., & Vidal, D. (2018). Tourism and religion sacred spaces as transmitters of heritage values Tourism and religion sacred spaces as transmitters of heritage values. Church, Communication and Culture, 3(3), 237-259.

- de la Torre Castellanos, R., & Zúñiga, C.G. (2005). La lógica del mercado y la lógica. Desaccatos, 18, 53-70.

- de la Torre, R., & Gutiérrez Zúñiga, C. (2005). Mercado y religión contemporánea. Desacatos 18, 9-11.

- Enríquez Acosta, J.Á., Guillén Lúgigo, M., & Valenzuela, B.A. (2017). Patrimonio y Turismo. Un acercamiento a los lugares turísticos de México.

- Esteve Secall, R. (2009). Turismo y religión. Aproximación histórica y evaluación del impacto económico del turismo religioso. Available online at: http://www.diocesisoa.org/documentos/ficheros/Esteve_Rafael_-_texto_786.pdf

- Fábregas, Andrés. (1986). La formación histórica de una región los Altos de Jalisco Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. Available online at: https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/La_Formación_Histórica_de_una_Región.html?id=uEUWAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y

- Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, J.A. (2006). Los Altos de Jalisco durante la guerra de reforma e imperio de Maximiliano Universidad de Guadalajara.

- Lanquar, R., & World Tourism Organization. (2007). Turismo y religiones. Una contribución al diálogo entre religiones culturas y civilizaciones. In World Tourism Organization Conferencia de Córdoba de la Organización Mundial del Turismo 11

- Machado Chaviano, E. L., & Hernández Aro, Y. (2007). Procedimiento para el diseño de un producto turístico integrado en Cuba. Teoría y Praxis 3(4), 161-173.

- Márquez, P. (1947). Historia de Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco. Talleres litográficos RADIO.

- Martínez Cárdenas, R. (2013). Santo Toribio Romo, un santo que vive entre migrantes y tequila. In La espiritualidad como recurso turístico: propuestas, experiencias y aproximaciones. UNIVERSIDAD DE GUANAJUATO.

- Martínez Cárdenas, R., & Mínguez García, M. del C. (2014). Tipologías de destinos para el estudio del turismo religioso. El caso de México. In De la dimensión teórica al abordaje empírico del turismo en México: perspectivas multidisciplinarias 51-66. UNAM. Available online at: http://www.publicaciones.igg.unam.mx/index.php/ig/catalog/book/47

- Martínez Cárdenas, R., & Mínguez García, Ma. del C. (2019). Es factible repetir el modelo del camino de santiago en México la ruta cristera y la ruta del peregrino. In R. J. S. Anderson Pereira Portuguez Ricardo Lanzarini Territoralidades do turismo dinâmicas e desafios dos mercados receptivos. 229-262.

- Martínez Cárdenas, R., & Reynoso Rábago, A. (2019). El patrimonio religioso como recurso turístico en los Altos de Jalisco. Journal of Tourism and Heritage Research 2(2), 207-230.

- Martínez Cárdenas, R., & Reynoso Rábago, A. (2019b). Entre la fe y turismo. Competitividad turística religiosa El caso de San Juan de los Lagos, México. Gran Tour: Revista de Investigaciones Turísticas 20(20), 73-90.

- Martínez Cárdenas, R., & Ruiz Aguirre, R. de J. (2021). La práctica del turismo religioso durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Un análisis de comunidades de Twitter derivado de la peregrinación de Amarnath Yatra India. Religiones Latinoamericanas Nueva Época, 171-192.

- Meyer, J.A. (1994). La cristiada. Siglo Veintiuno. Available online at: https://books.google.com.mx/books/about/La_cristiada_La_guerra_de_los_cristeros.html?id=xqhbJ3GZ8X4C&redir_esc=y

- Ruezga Gutiérrez, S., & Martínez Cárdenas, R. (2011). El turismo por motivacion religiosa en México. El caso de San Juan de los Lagos. Cuadernos Del Patrimonio Cultural y Turismo. Available online at: http://www.cultura.gob.mx/turismocultural/cuadernos/pdf14/articulo13.pdf

- UNESCO. (2010). Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. Centro Del Patrimonio Mundial. Available online at: https://whc.unesco.org/es/list/1351