Research Article

COVID-19 AND OBSTACLES TRASH PICKERS EXPERIENCING: THE CASE IN CIRENDEU AND OTHER REFERENCES IN PUBLICATIONS

1057

Views & Citations57

Likes & Shares

COVID-19 pandemic crashed the livelihood of people world-wide. The trash pickers, people who pick up waste and sell it for the livings, are one of the most vulnerable people influenced by this fatal situation. Many researchers have studied on them and concluded that they are constantly exposed to life-threatening conditions due to various factors despite of their enormous contributions to the recycling. The situation of COVID-19 exacerbates their circumstances. This paper will first, introduce the livelihood and the waste disposal system of the trash pickers community in Cirendeu, Indonesia to offer an idea of who trash pickers are, using the paper published in 2019 by the author. Then it also pursues research to examine the situation of trash pickers in Indonesia under COVID-19 mostly comparing the situation back in Asian Financial Crisis in 1997.The author has visited the communities several times before the pandemic of COVID-19 and keeps researching on their communities and their activities as well as other Indonesian locals via internet. The further research is done by interviewing, reading relevant articles and joining online lectures and conferences. The results from the research indicate that even though their activities are needed now more than ever, their health and living status are threatened especially under the pandemic. In order for them to secure their lives and waste disposal work, it would be necessary to consider the intensive supports from the government as well as the mutual aids provided by the community and various kinds of groups.

Keywords: Environment, Health, Waste disposal, Trash, Pandemic

INTRODUCTION

Since global warming is widely recognized, people has been striving to solve the environmental issues. There have been many protocols and goals suggested, and governments enacted laws and regulations. Many of them aim to reduce emission of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, use of plastics, and to encourage recycling; however, people who inconspicuously contribute to achieve those goals behind the trash are barely appreciated.

Since the waste management law enacted in 2008 is evaluated as a vague and ambiguous regulation which lacks strong enforcement and socialization, trash pickers must be playing a crucial role in the waste management in Indonesia(Purba & Erliyana, 2020)Considering the comments above, the author assumes that the specific method of the waste disposal system in Indonesia is still the one that’s called End of Pipe technique; basically the trash goes through three steps which are generation, collection, and disposal at the open dumping landfill. (Sakumoto & Kojima,2007) Further more, the data indicates that about 55% of the waste in Indonesia ends up open dumping landfill called the final disposal site, generally a landfill of open dumping. (Sakumoto & Kojima, 2007)This mountain of trash at the site jeopardies human lives without any proper management such as an accident occurred in 2005 killing 143 people and destroying 71 houses at the open dumping site in Bandung because of landslide and methane gas explosion.(Lavigne et al., 2014)This incident could have been prevented from happening if there were appropriate management implemented. The situation like this spurs contamination of the land and causes more accidents which imperil their lives.

Therefore, while every human strives to protect the environment, it is also crucial to consider human security of those underrated people’s situation and appreciate their activities. In this paper, the author will introduce trash pickers and their lives in Cirendeu, Indonesia, to provide a specific example of who the trash pickers are and how their waste disposal functions. Many researchers have revealed trash pickers’ work focusing on Bantar Gebang, Bali or other developing countries. (Devi, 2017; Sasaki & Araki, 2013; Zurbrügg, Gfrerer, Ashadi, Brenner, & Küper, 2012) Furthermore, this paper attempts to inform the threats they are facing under the situation of COVID-19 by researching documents. There have also been many researches published by scholars investigating obstacles those impoverished people face under a similar tough circumstance such as Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. By scrutinizing the similar case in the past and the current situation, it should suggest the critical problems and the better aids to alleviate the condition.

This paper will be followed by method, result and discussion, conclusion and acknowledgement. In the method section, the author describes the procedures of fieldwork and interview. The specific information about the trash pickers in Cirendeu area will also be provided in this section based on the author’s research published in 2019. The author will add some research documents to propose the potential menace triggered by COVID-19 referring to the research focusing on Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 as a similar catastrophic event. In the results and discussion section, the author will discuss the current situation under COVID-19 referring to the documents and lectures she attended. In the conclusion section, the author specifies the findings and the importance of paying attentions and supporting for those unappreciated essential workers for recycling under COVID-19. In the acknowledgement section, the author will show her appreciation to people who supported her during the research. In the reference section, the author will list the documents which the author refers in the paper. The author has read and been inspired from many other books and documents other than those listed at the end.

METHODS

In the research, the author uses the method of interview and document investigation and lectures. First of all, the author introduces the community of Cirendeu based on the fieldworks conducted three times in August 2017, August 2018 and June 2019. She has kept in touch with the community since 2013, therefore, she embeds photo taken before the fieldwork as well. In this paper, the author will explain their profile and activities, briefly reiterating the research paper written by the author in 2019. The specific location is Jl. Cirendeu Indah II RT 01, RW 01, Tangerang, West Java. The population of the community is estimated 200 people which includes 70 students. The adults are the first generation to migrate to the area; in 2004, they have been evicted from Terogong (South Jakarta) area, the place where they used to live. Those students go to kindergarten, elementary school, middle school, high school and college. The residents of the community consist trash pickers, warung owner, NPO staff, maids and children. Warungis an Indonesian local food vendor. There were two warung owners who were both wives of the trash pickers. They purchase products from local markets and sell them inside the community to earn extra income other than the wages of their husbands. An NPO staff works for XS Project (XS Project is “a local non-profit organization (...) which has been communicating and supporting the trash pickers for a decade” (Kakinuma, 2019) by buying trash which are usually categorized as unsellable plastics at normal recycle shops. They create products from those trash bought from the trash pickers and donated trash from companies and allot its sales to various programs to assist the trash pickers and their children including educational fee and medical fee. According to Retno Hapsari, the manager interviewed in 2020 online, XS Project now has two entities: an NPO and a company due to the increase in the scale of its activities) and the community as a communicator: preparing school related papers and attending meetings of the students of the community on behalf of their parents, informing XS Project of circumstances of the residents, and managing the facilities built by donations through XS Project. Also a few wives of the trash pickers are employed as maids at the wealthy families near the community. Six of the students now became the first generation to attend to university, majoring various studies like technology, management, and admissions while working as tutors for the elementary students in the community, hired by XS Project as part-time job workers. XS Project supports those students including other grades by paying their school fees to encourage them to continue going to school and providing other necessities. XS Project also arrange two professional tutors from outside the community to assist the students to finish their homework assignments.

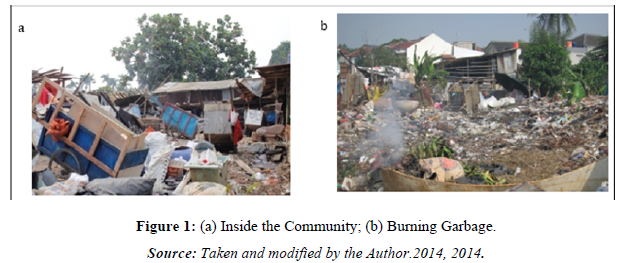

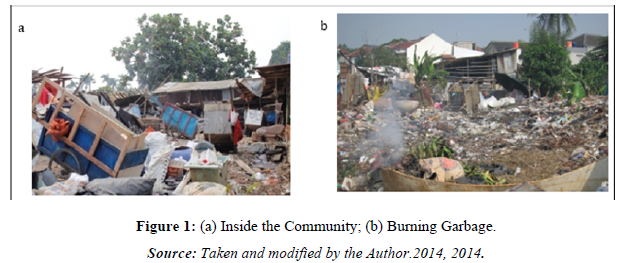

Following figures are the pictures of the community. As in Figure 1(a), the area is filled with trash. The children run around and play with their friends there with flip flops or even bare foot. Figure 1(b) illustrates the polluted air and contaminated land inside their residence. The residents breathe in the carbon dioxide and other hazardous gases emitted by burning useless unrecyclable garbage which often cause health issues related to eyes and lungs.

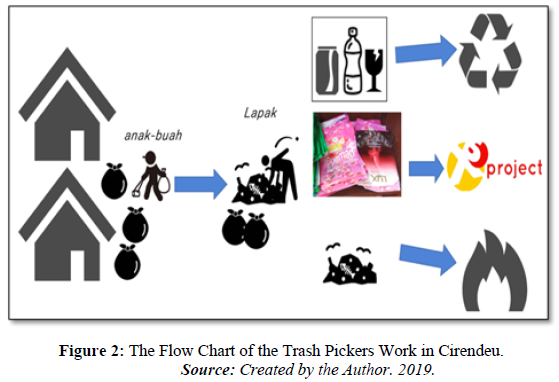

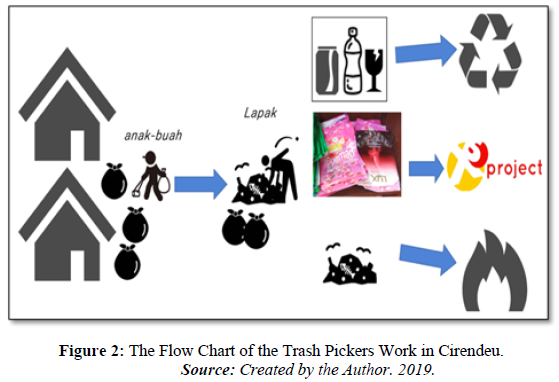

The waste disposal of the trash pickers in Cirendeu is as shown in Figure 2 below. As previous researches done by Sasaki(Sasaki & Araki, 2013; Sasaki, Araki, Tambunan, & Prasadja, 2014; Sasaki, 2015) revealed their systematic waste disposal in Bantar Gebang, the trash pickers in Cirendeu area also play their specific roles in their work in spite of its relatively small population compared to those major trash pickers’ community surrounding the final disposal site such as Bantar Gebang. In Cirendeu, there are two main roles involved in the flow: lapak and anak-buah. Anak-buah collects trash from house to house, carry them back to the community and sell it to his boss, lapak. Lapak sorts recyclables and unrecyclable and bring sellable materials to each Organization such as recycle shops and XS Project. Anything considered as non-valuables are burnt inside the community, near their houses.

The waste disposal of the trash pickers in Cirendeu is as shown in Figure 2 below. As previous researches done by Sasaki(Sasaki & Araki, 2013; Sasaki, Araki, Tambunan, & Prasadja, 2014; Sasaki, 2015) revealed their systematic waste disposal in Bantar Gebang, the trash pickers in Cirendeu area also play their specific roles in their work in spite of its relatively small population compared to those major trash pickers’ community surrounding the final disposal site such as Bantar Gebang. In Cirendeu, there are two main roles involved in the flow: lapak and anak-buah. Anak-buah collects trash from house to house, carry them back to the community and sell it to his boss, lapak. Lapak sorts recyclables and unrecyclable and bring sellable materials to each Organization such as recycle shops and XS Project. Anything considered as non-valuables are burnt inside the community, near their houses.

Anak-buah and lapak have an interdependent relationship not only at a business side but also at in a livelihood. Once they become an anak-buah, his lapak builds his house and sometimes a cart to transport waste. The anak-buah pays his rent to the lapak by gathering and delivering the trash. In a case they cannot collect waste anymore due to any reasons, the rent will be paid in cash to lapak. At the time of the research, there were five lapak and each of them had about 10 anak-buah working under each lapak. Hapsari also mentioned that there is a trash collector who are contracted with a family for routinely trash picking and paid salary. The specific contribution of their work to recycle in Indonesia in a number was calculated in the author’s research paper in 2019. Based on the data XS Project collected, it was concluded that the amount of waste they sold to XS Project each year from 2017 to 2019 covered the amount of waste generation per capita per year in Indonesia. In 2017, it reached more than the twice amount of the waste generation per capita. The number was astonishing; the calculation regarded the number of recyclables brought to XS Project only. It is evident that it would be much bigger number if the calculation included the recyclables, they sold to other recycle shops. Moreover, it should also be noted that the size of the community in Cirendeu is relatively small compared to those in major dumpsites. Thus, it is expected to be enormous contribution to recycling if the calculation takes account of all works of trash pickers in Indonesia. Medina also comments that their activities in Jakarta alone contribute to recycle one third of the total waste generation of the city.(Medina, 2010)Besides the recycling, they also play a vital part of daily city cleaning and its sanitation.(Wizer, 2005).

Not with standing, their living status has been quite unstable and unsecured. (Wizer, 2005) Especially under COVID-19, their life and activities will be threatened by numerous obstacles. Such an unprecedented event had been occurred in Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. The influence damaged the economy and livelihood of the people; in Indonesia, about one fourth of which suffered in poverty in 1998 due to the impact afterward. (Hondai & Shintani, 2008; Takeda, 2002)Although causes of the two events and the category differ (UNDP categorizes COVID-19 pandemic as health crisis while Asian Financial Crisis is generally categorized as financial crisis according to Britannica), Asian Financial Crises are often cited when discuss about COVID-19 mainly because they both share the same traits: The calamitous effects on a whole nation (Jiao & Sihombing, 2020; Jihiki, 2020; Touhou, 2021). Therefore, this paper considers detriments and barriers they faced back then are comparable with what they would face nowadays under the confusion. The following researches are not specifically focusing on the trash pickers but in general; however, it should emphasize that their circumstances must had been worse since they are considered as the one at lowest hierarchy of the society (Devi, 2017; Sasaki, 2015).

In 1998, Indonesian government lunched Social Safety Net Program to mitigate the hardship people suffered from due to the crisis. The program targeted the socially vulnerable people who were severely influenced by the crisis based on the data of National Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN Badan Kordinasi Keluarga Berencana Nasional in Indonesian) included food distribution, school related campagines like scholarship, providing free health insurance cards, and job creation related to infrastructures (Takeda, 2002). However, many researchers castigate serious failures of the programs. To begin with, the data applied for the beneficiary selection lacked credibility. The data did not cover those who fell under poverty line recently because the program was too urgent to collect and scrutinize the financial status of each citizen ( Takeda, 2002). It could be also added that even they had probed each condition, some impoverished people would have still been missed out form the list because those people would have hesitated to register their financial status as beneficiaries under the poverty line due to the tendency to refuse acknowledging their condition as poor and to conceal their situation ( Kurasawa, 2001). It is also reported that due to the mobility of people, many did not obtain national identification cards (KTP Kartu T and a Penduduk in Indonesian) which were required to benefit from the subsidies. (Takeda, 2002)Furthermore, it is pointed out that some regions distributed the supply equally to everyone; some of who considered as relatively wealthy also received the support as much as the needy people did. (Motodai & Shintani, 2008) There was also a case where the government reformation did not work as intended. The government decided to transfer funds for underweight pregnant women and infants directly to each district to avoid embezzlement; however, the flow after the district wasn’t as smooth as expected. Kurasawa mentioned in her book that no one in her village in Lenteng Agung, located in South Jakarta, had recognized the fund at all. ( Kurasawa, 2001)On the other hand, the program launched and operated by the neighboring community itself and other organizations other than the government were noteworthy. In Lenteng Agung, the representatives of the neighborhood association, RT (Rukun Tetangga is the lowest administrative division. The system is implemented under Japanese occupation during World War II. Suharto, the second president of Indonesia, strengthened the administration to control votes and watch communists) and the mayor agreed to start a collaborative activity called Lumbung Beras; relatively affluent residents in RT donate 10kg of rice each month, send it to the community association, RW(Rukun Warga is an administrative division under the village. RT functions under RW), and then the rice were delivered to households counted as poor. ( Kurasawa, 2001)There were also many other goods donated by various organizations including local students and international groups. One of which was distributing Nine Necessities of Daily Living, sembako, (Sembilan Bahan Pokok in Indonesian. The nine are rice, oil, sugar, fruits and vegetables, meats, eggs, milk, cooking gas, and salt )sometimes for free and sometimes at discounted price (Kurasawa, 2001). As above, Indonesian locals had overcome the crisis with supports and mutual aids they had within the community although it might had been much easier if the government policy didn’t malfunction; however, those hopeful examples were the residents under an administrative district. The trash pickers in Cirendeu are not registered as local residents, meaning they are not on the list of the administrative district of RT nor RW; therefore, they might highly possible to fall out from the relationship of the mutual aids.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

As Hughes stated the informal trash pickers as “particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus pandemic”(Hughes, 2020), they do suffer from various obstacles mostly economic and medical problems; some of which are quite similar to those happened in Asian Financial Crisis. The specific factors are mainly three points. The first is the data associated with the governmental problems. The second is working and economic condition. The third is of course medical issues. The specific explanation and discussion are following.

As mentioned, they are facing quite similar issues with those reported during Asian Financial Crisis. The first and the most essential critique was still about the credibility of the data. The government allocated about 7,500 million US dollars to launch safety net programs which include direct cash transfers to the needy people and distribution of basic food; however, there were a lot of cases where impoverished households been unqualified as beneficiaries of the supports while some relatively wealthy families been qualified. Although the village headmen submitted the list of destitute people in the community, some aids weren’t distributed accordingly ( Honmyō, 2020). The locals blame on the local government for the impropriety, and the local government chastises the central government for the mismanagement of national data. On the other hand, the central government berates the local government that the confusion of the data is caused by the laziness of the local government who are too reluctant to update their local data and report it to the central ( Honmyō, 2020). Pepen Nazaruddin, general director for social security and protection at the Social Affairs Ministry of the Republic of Indonesia confesses the difficulty and the delay of the distribution due to the geographical and confirmation problem (Damayanti & Tani, 2020). It should also be noted that not every people in Indonesia have bank accounts to receive the cash transfer which might make the situation even more difficult. The manager of XS Project answered the interview online about the situation of the trash pickers in Cirendeu in 28th, August 2020. According to her, while the government attempted to dispatch the supplies, it totally depends on the decision made by RT which families to be the recipients of the supplies. As Kurasawa researched during Asian Financial Crisis, it might be an advantage of RT to control the material supplies within the community; however, in most cases trash pickers are outsiders who do not even have KTP(Alliance of Indian Wastepickers, 2020). In a case of the community in Cirendeu, they have KTP which are registered in their hometown outside Tangerang, meaning that they are considered as non-local residents. Thus, they are mostly ignored from the local RT; however, XS Project and other generous organizations donated staple food and hand sanitizers to the community. Pris Polly Davina Lengkong, the president of Indonesian Waste-pickers Union (IPI Ikatan Pemulung Indonesia in Indonesian)pleaded with the government to support the trash pickers to protect their health and welfare, and to acquire KTP though the video, asserting that KTP is an imperative item to receive aids from the government. He also showed his gratitude towards private enterprises for their donation such as installment of washing room and distribution of masks from PAM Jaya, handout of soaps form Unilever, and additional food supplies from Indofood (Alliance of Indian Wastepickers, 2020). The waste pickers in Bantar Gebangare also excluded from the aids for COVID-19 from the government because they are not registered as locals. (Dean & Paddock, 2020); however, Resa Boenard, the founder of an NPO, Seeds of Bantar Gebang comments that the reason why the waste pickers in Bantar Gebang do not proceed the registarion is because they stay their temporally and feel vacillation towards being a resident of the dumpsite (Boenard, 2020). The second issue is about the work. During Asian Financial Crisis, it was reported that about the unemployment rate increased from 4.9% to 6.4% from 1996 to 1999 (Takeda, 2002). It is mostly due to the financial and economic problems of the companies and private enterprises. Under COVID-19, new problem arises: Lockdown. Since February 12th 2020 when Indonesian government officially suspended landing of any aircrafts from China, the government executed various regulations in order to stop spreading pandemic. The Large-Scale Social Restriction (PSBB Pembatasan Social Berskala Besar in Indonesian) is one of the well-known decrees enacted in Indonesia. The details of PSBB are adjusted by each local government and modified through time, but the once enforced in Jakarta in April 10th 2020 obliged wearing masks, work from home excluding essential works and other public services, number restrictions of passengers in transportation, and complying with specimen test when requested; those who disrupt the decree would be imposed penalty including criminal charges (Retrieved from the Embassy of Japan in Indonesia’s web page(“Implementation of large-scale social restrictions in Jakarta Capital Special State (Governor's Ordinance / Decision Issued”2020)). As medical perspective, enforcing PSBB in major cities are relevant and vital; however, this also disturbed the waste disposal of the city especially those ran by trash pickers. The physical interruption happened during the waste collection process. According to Hapsari, the trash pickers are instructed to go back home by police when they walk around to collect the waste. The garbage chute in the housing complexes are also guarded by the security; it is required to get disinfectant, temperature checks, and masks to go in there. She also discloses that sometimes the police spray the trash pickers with disinfectant when they are walking to collect the rubbish. Lengkong conveys that waste pickers in Garut and West Bandung were invaded by police and Municipal Police (Satuan Polisi Pamong Praja, generally called “Satpol PP”) asking their work to be shut down. He adds that staying home is not a realistic choice for the waste pickers who need to earn a daily living every day to survive and buy the basic needs for the day (Alliance of Indian Wastepickers, 2020). Their earnings are simply not enough for the savings. Although they are allowed to go out to scavenge, the next barrier awaits them; the close of recycle shops. They basically have few places to sell collected rubbish. Obviously, their income declined drastically. According to Hapsari, the average monthly income of anak-buahdropped from Rp.300.000 to Rp.400.000 before COVID to Rp.150.000 or sometimes Rp.120.000 during COVID. The average monthly income of the trash collector dropped from Rp.500.000 down to Rp.250.000. For lapak, the circumstance is harder; although they continue buying waste from their anak-buah, lapakhave no place to sell it so they need to keep them until the recycle shops and factories been opened; however, she also explained that even the situation of lapak is pretty hard, they still lend their money to anak-buahif they needed. Their relationship of mutual aid still works even under such a touch circumstance. Boenard clarifies the depreciation of plastic from Rp.2.000 to Rp.4.000 per one kilogram before COVID-19 down to Rp.300 to Rp.400 today (Boenard, 2020). She stats the adversity they experience in Bantar Gebang but also appreciates for their fortunate of being donated to supports the waste pickers there; however, while the price is dropped drastically, the amount of plastic waste has been increased due to stay home. Evidently, people during stay home utilize food delivery services which often use plastic. It is also pointed out that single-use plastics such as personal protective equipment including gloves and masks occupy a portion of plastic waste nowadays (East, 2020). Under such a situation, even if they were permitted to pick up the waste, they wouldn’t not collect plastics because it doesn’t worth it anymore. The plastic recycling activities might stop and the mountain of plastic waste might grow. This phenomenon causes two issues: Environmental issues and medical issues which will be addressed later in this section. The last point would be the medical problem. Even before the pandemic, their lives are always exposed to the dangers. As mentioned, the houses built on the mountain of trash are easily destroyed due to the heavy rain, landslide and sometimes explosion of a gas accumulated underground. Hapsari explained that their nutritional condition is poor; the common disease found in the community in Cirendeu were typhoid and tuberculosis (Hapsari, 2017). Some also get injured from stepping on pointed objects such as glass which might cause tetanus. They cannot afford treatment costs, they chose not to go to the hospital to receive medication but just to leave the wound which might aggravate the injury. XS Project has prepared health program for the trash pickers in Cirendeu. They have dedicated to contract with Medicatama 8 clinic to send the nurses to the community to teach the villagers nutrients and daily sanitation, and to pay for their medical costs such as vaccination, X-ray inspection for tuberculosis, contraceptive devices, and surgery and hospital charges in case of emergency. Now, they are confronted with excessive medical wastes in the dumpsite which might infect them COVID-19. In March 2020, the growth in medical waste recorded 30% compared to the previous month in Jakarta (Kojima, Iwasaki, Johannes, & Edita, 2020). Those who encounter with the medical waste especially in the informal sectors are highly possible to be exposed with transmission. (“Managing Infectious Medical Waste during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” 2020). Indonesian government apply legislation on the Law on Solid Waste enacted in 2008, and Environmental Health Standards for Hospitals in 2004 to regulate the medical wastes but they “both often lack practical application” (Tsukiji, et al., 2020) suggesting that in most cases, the infectious wastes are abandoned in the disposal site without an appropriate treatment. XS Project has conducted health check-ups with the trash pickers in Cirendeu on COVID-19. Hapsari explained that they hesitated to take the test at the beginning; once the result was positive, they wouldn’t be able to continue working, meaning that they would produce no income. However, with the persuasion, some residents decided to join the test. In Indonesia, there is a myth that those who live in an unsanitary place are immune to diseases including COVID-19, which worsens the situation by making the waste pickers not afraid of COVID-19 (Dean & Paddock, 2020).

CONCLUSION

As a conclusion, the author agrees with the quote from Kurasawa commenting on the livelihood of the local residents in Lenteng Agung that social policies which should have been conducted by the government are ignored, and many of those depends on self-help efforts and the mutual assistance network of the residents (Kurasawa, 2001). Although this comment does not particularly address to the unprecedented situation like Asian Financial Crisis or COVID-19, what she noted back then still reflects the society in Indonesia when analyzing the circumstances under COVID-19. Indonesia is world 4th most populated countries inhabited by about 260 million in 14th largest land area of archipelago which lays about 5000 kilometers from east to west. It is understandable how difficult and complicated to function governmental aids and to enforce legislation under COVID-19 in every single region. By considering the fact that some portion of the population do not acquire national ID or even registered as residents, a probe on national status would be such a challenge. Setiati and Azwer also observes that it “may be unlikely for the government to cover the daily needs of the affected individuals nationwide”. (Setiati & Azwar, 2020)They proposed an alternative solution to count on donations from wealthy Indonesians, citing the CAF World Giving Index in 2018 where Indonesia recorded the top among all countries (Setiati & Azwar, 2020). Although it might be too much to ask for the citizens, they might as well need to collaborate and help each other within the community for now; innovation and reformation on the government and its management would most probably be procrastinated. Therefore, further researches on the community-based approaches of safety-net programs should be done. The keyword for the research might be gotong royong, widely recognized as an Indonesian custom of mutual assistance (Kurasawa, 2001; Kobayashi, 2006). Pandu Riono, a doctor of Epidemiology and a senior faculty of Public Health at University of Indonesia suggested that the transmission of COVID-19 now moved its place into the neighboring community, not a city-wide; thus, the essential activities required today is “community controlling”.(Riono, 2021)He also mentions that they need to learn from Thailand as a successful example of the community controlling.

The limitations of the research are followings. One, the data are not based on the actual fieldwork and face-to-face interview because of COVID-19; therefore, it might be considered as lacking credibility compared to those conducted in the field. It also lacks a specific number of case and patients of COVID-19 confirmed in the waste pickers community. The author simply could not find the credible evidences which could be referred in this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (IF ANY)

I would like to show my appreciation to the following people for helping me with this research: The villagers of Cirendeu and the interviewees for accepting me as a researcher in their community.

Bedah for arranging the schedule of the research and interviews, and helping me understand Bahasa Indonesia.

XS Project manager, Retno Hapsari and all XS Project staffs for introducing me to the trash pickers community in Cirendeu and kindly sharing the data they collected.

Keio University Associate Professor. Yo Nonaka for assisting and teaching me the tactics of fieldwork, interview and writing a research paper.

Indonesian Heritage Society for providing opportunities to hear directly from professionals by holding various online lectures.

My family for their continuous support and encouragement.

- Anjani, A. (2011). Master Thesis Household Waste Management in Indonesia: What is an effective means to household waste reduction in Indonesia? Tohoku University.

- Alliance of Indian Wastepickers. (2020). Indonesian Waste-pickers in a Dire Situation due to the COVID-19 Lock-down. Available online at: https://globalrec.org/2020/04/27/indonesian-waste-pickers-in-a-dire-situation-due-to-the-covid-19-lock-down/

- Boenard, R. (2020). Face Your Waste. Indonesian Heritage Society. COVID-19 pandemic Humanity needs leadership and solidarity to defeat the coronavirus. Available online at: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/coronavirus.html#:~:text=The coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic,to every continent except Antarctica.

- Damayanti, I., & Tani, S. (2020). Jokowi and Indonesia’s jobless angry at COVID cash handout delays. Available online at: https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Jokowi-and-Indonesia-s-jobless-angry-at-COVID-cash-handout-delays?n_cid=DSBNNAR

- Dean, A., & Paddock, R.C. (2020). Jakarta’s Trash Mountain: ‘When People Are Desperate for Jobs, They Come Here.’ Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/world/asia/indonesia-jakarta-trash-mountain.html

- Devi, S. (2017). Surviving on Waste: A Study of Waste Pickers. International Journal of Academic Research and Deveopment 2(6), 1229-1232.

- Hapsari, R. (2017). XS Project. In M. Kakinuma (Ed.), words for kiwanis presentation. Saitama.

- Hughes, K. (2020). Protector or polluter? The impact of COVID-19 on the movement to end plastic waste. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/plastic-pollution-waste-pandemic-covid19-coronavirus-recycling-sustainability/

- Jiao, C., & Sihombing, G. (2020). Indonesia Set for First Recession Since Asian Financial Crisis. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-04/indonesia-set-for-first-recession-since-asian-financial-crisis

- Kojima, M., Iwasaki, F., Johannes, H.P., & Edita, E.P. (2020). Strengthening Waste Management Policies to Mitigate the COVID-19 Pandemic. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

- Lavigne, F., Wassmer, P., Gomez, C., Davies, T.A., & Sri Hadmoko, D., (2014). The 21 February 2005, catastrophic waste avalanche at Leuwigajah dumpsite, Bandung, Indonesia. Geoenvironmental Disasters 1(1), 10.

- Managing Infectious Medical Waste during the COVID-19 Pandemic. (2020). Asian Development Bank.

- Medina, M. (2010). Scrap and Trade: Scavenging Myths. Our World. United Nations University Available online at: https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/scavenging-from-waste

- Purba, L.A.H., & Erliyana, A. (2020). Legal Framework of Waste Management in Indonesia. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 413.

- Riono, P. (2021). Indonesia on the Other Side of This Pandemic. Indonesian Heritage Society.

- Sasaki, S., & Araki, T. (2013). Employer–employee and buyer–seller relationships among waste pickers at final disposal site in informal recycling: The case of Bantar Gebang in Indonesia. Habitat International 40, 51-57.

- Sasaki, S., Araki, T., Tambunan, A.H., & Prasadja, H. (2014). Household income, living and working conditions of dumpsite waste pickers in Bantar Gebang: Toward integrated waste management in Indonesia. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 89, 11-21.

- Setiati, S., & Azwar, M. (2020). COVID-19 and Indonesia. Acta Medica Indonesiana 52, 84-89.

- Tsukiji, M., Gamaralalage, P.J.D., Pratomo, I.S.Y., Onogawa, K., & Alverson, K.,(2020). Waste Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic From Response to Recovery. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/33416/WMC-19.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Wizer, A. (2005). XSProject. Artlink 25(4), 70-73.

- Zurbrügg, C., Gfrerer, M., Ashadi, H., Brenner, W., & Küper, D. (2012). Determinants of sustainability in solid waste management- The Gianyar Waste Recovery Project in Indonesia. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.) 32, 2126-2133.

- Implementation of large-scale social restrictions in Jakarta's Special Capital Province (issue of Governor's Ordinance / Decision). (2020).

- Sasaki. S.,(2015). Informal recycling at final waste disposal site: Taking the case of Vantal Guban waste final disposal site in the Republic of Indonesia (University of Tokyo (University of Tokyo)).

- Sakumoto, N., & Kojima, M., (2007). Indonesian Industrial Waste / Recycling Policy. Industrial Waste / Recycling Policy Information Providing Business Report in Asian Countries 225-245.

- Kurasawa, A, (2001). Jakarta back-alley field note. Chuokoron-sha.

- Jihiki, K., (2020). Indonesia's recession since the currency crisis Corona was down 3.49% year-on-year in the July-September quarter.

- Kobayashi, K., (2006). Institutionalization of tradition" in Java during the Japanese occupation-Tonarigumi system and Gotong royong. Asian economy 47, 2-29.

- Hondai, S., & Shintani. M., (2008). Education and Income Gap Toward Poverty Reduction in Indonesia.

- Honna, N.H. (2020). Politics of Data.

- Higashi. S. (2020). New coronavirus and waste management in emerging countries.

- Touhou,T. (2021). Indonesia in the New Corona Disaster (2)-Impact on Employment. IDE Square-Eyes to See the World, 1-8.

- Takeda, N. (2002). Chapter 5 Asian Currency Crisis and Indonesia's Social Safety Net Program. In Asian Currency Crisis and Assistance Policy: Indonesia's Challenges and Prospects. Japan Trade Promotion Organization Asian Economic Research Place 171-207.

- Takakura, K., & Shirai,Y.(2016). Survey on the role played by kitchen waste composting technology in developing countries and its effects. 2, 84-91.

- Nakachi, S., & Fujimoto, N. (2013). Current status and issues of waste treatment in Indonesia. Overseas Business Research Research Series 98 40(2), 107-121.

- Miyake, H. (2018). A Study on Social Consideration for Waste Collection Children. 8, 41-56.

- Watanabe, K., Zhang, K., Irwan, D., & Sasaki, S. (2016). How much economic development will prevent the final disposal site scavenger from being established: From a comparison between Malaysia and Indonesia. Meeting 115-116.